Partap College of Education, Ludhiana, Punjab India

Corresponding author Email: moneypreet74@gmail.com

Article Publishing History

Received: 19/06/2019

Accepted After Revision: 18/09/2019

Well-being in adolescence is an increasing field of study. Well-being, as a component of quality of life, has been a field of important developments during the last two decades. Adolescent well-being is a comprehensive construct that includes the ability to acquire knowledge, skills, experience, values, and social relationships, as well as access to basic services, that will enable an individual to negotiate multiple life domains, participate in community and civic affairs, earn income, avoid harmful and risky behavior, and be able to thrive in a variety of circumstances, free from preventable illness, exploitation, abuse and discrimination. The purpose of the research is to find out the level of well-being of adolescents. Participants of the study are 640 secondary school adolescents from the state of Punjab. Survey was used to study the level of well-being of adolescents. The findings show that out of total 640 adolescents, 196 adolescents i.e. 32.67% of adolescents have high well-being, 392 adolescents i.e. 65.33% have average level of well-being and only 12 i.e. 2% have low level of well-being. A majority of adolescent boys and girls have average level of well-being. Majority of rural adolescents have average and majority of urban adolescents have high level of well-being. This study highlights the importance of considering well- being of adolescents. These results have strong implications for adolescent’s positive mental health promotion, including school-based policies and practices.

Adolescents, Well-being

Kaur M. Analysis on the Level of Well-Being Among Indian Secondary School Adolescents. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2019;12(3).

Kaur M. Analysis on the Level of Well-Being Among Indian Secondary School Adolescents. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2019;12(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/2lXF3dC

Copyright © Kaur, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) https://creativecommns.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use distribution and reproduction in any medium, provide the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Adolescence stage is the progressive transition from childhood to adulthood, it is a phase when many important biological, economic, social and demographic events set the stage for adult life. It is a transitional stage of psychological and physiological development from puberty to adulthood. There are more than 1.2 billion adolescents worldwide indicating that roughly one in every six persons is an adolescent. About 21% of Indian population is adolescents (about 243 million). It is well recognized that India’s ability to achieve the Millennium Development Goals and to achieve its population stabilization goals will depend on the investment made in its young people. They are the future of the nation, forming a major demographic and economic force. They have specific needs which vary with gender, life circumstances and socio economic conditions. In India large number of adolescents face challenges like poverty, lack of access to health care services, unsafe environments etc. Adolescence is a period of preparation for undertaking greater responsibilities like familial, social, cultural and economic issues in adulthood. It is a critical developmental period with long-term implications for the health and well-being of the individual and for society as a whole. Each year, an estimated 20 % of adolescents experience a mental health problem, most commonly major depression or other disturbances of mood. Mental health problems in adolescence, if unaddressed, can carry over and negatively affect individuals over long term. A major depression experienced for the first time in adolescence, for example, can persist or recur through adulthood, (Essen & Martensson, 2014 Easow and Ghorpade (2017).

In India, data on adolescents from national surveys including National Family Health Survey III (NFHS-3), District Level Household and Facility Survey III and Sample Registration System call for focused attention with respect to health and social development for this age group. Therefore, it has been realized that investing in adolescent mental health will yield social and economic dividends to India. Thus well-being in adolescence is an increasing field of study. Well-being, as a component of quality of life, has been a field of important developments during the last two decades. However, its study in relation to childhood and adolescence has been, comparatively speaking, much more limited despite the fact that during the 1990’s an increase of interest towards the development of adequate instruments has taken place, these instruments being more sensitive to age and the evolution period of the individuals (Casas et al., 2000).

The concept of well-being has a multidimensional constitution, it could be a representation of positive feelings, individuals experience as well as aspects of life characterized by optimal functioning and flourishing (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). It has been asserted that it is practical to assume that the concept of health is comparable to the concept of well-being (Essen & Martensson, 2014). Research in well-being has been growing in recent decades (e.g., Diener et al., 1999; Kahneman, s1999; Keyes, et al. 2002; Stratham & Chase, 2010; Seligman, 2011) yet the question of how it should be defined remains unanswered. In the research Ryff and Keyes (1995) identified that the absence of theory-based formulations of well-being is puzzling. The question of how well-being should be defined (or spelt) still remains largely unresolved. Thomas (2009) also argued that well-being is intangible, difficult to define and even harder to measure.

The well-being issues are a growing concern in the school and for the community counselors, and educators. Research studies have revealed an increasing incidence of depression and other mental health issues among the youth (adolescent health and development W. H. O.). In fact, increasing incidences of suicide in adolescents have attracted more attention of the concerned authorities (Sharma et al., 2008). Now a days adolescents are deeply concerned as to how others view them and are apt to display self consciousness and are embarrassed on being criticized by others (Mahajan & Sharma, 2008). High prevalence of behavioral & emotional problems are also found in Indian adolescents (Pathak et al, 2011).Research conducted in the state of Rajasthan of India by Easow and Ghorpade (2017) revealed that the majority of 84(84%) adolescents had adequate psychological well-being and 11(11%) of them had moderate and only 5(5%) of them had inadequate psychological well-being. Viejo et al. (2018) in their study of Spanish adolescents showed good scores of psychological and subjective well-being among the adolescents, with a significant impact of sex and age in both measures of well-being.

Due to the increasing maladjusted behavior manifested by adolescents and against the proven empirical facts that a person is not necessarily inherently stressful, it is necessary to have a look at the factors that contribute to well-being of individual. Last decade’s research has highlighted the relationship between well-being and various other factors such as locus of control, stress, coping, meaning of life, family climate and parental autonomy-support & parent relationship with adolescent (Kunhikrishan & Stephen, 1992; Lekes et al., 2010; Rathi & Rastogi, 2007; Schlabach, 2013; Sehgal & Sharma, 1998; Seaton & Yip, 2009; Vandeleur et al., 2009; Vera et al., 2011 and Walsh et al., 2010). Well-being also found to be correlated with self-esteem, physical self identity, age, social support and positive psychological strengths (Jovic- Vranes et al., 2011; Karatzias et al., 2006; Khan, 2013).

Material and Methods

Research Questions

- What is the level of well-being among Indian adolescents?

- What is the relationship of well-being of adolescents in with gender and locale?

Sample

Descriptive survey method was used to investigate the level of well-being among adolescents. The present study was conducted on 640 secondary school adolescents from the state of Punjab. The total sample for the study was selected by multistage randomization, meaning thereby, randomization was followed at the district, tehsil, block, school and student level. The sample of the present study was raised from four randomly selected districts of Punjab viz., Ludhiana, Moga, Gurdaspur and Ferozepur out of the total twenty-two districts. For the study, ten schools (five rural and five urban) were picked up at random per district.

Data Collection

Quantitative method was used to collect and analyze data obtained from respondents. Well-Being Scale (WBS) by Singh and Gupta (2001) was used to address the research objectives. All permissions were requested and anonymity. Confidential use of information was guaranteed, and it was only used for statistical treatment and for the purposes of the research.

Data Analysis

The adolescents were classified into following three categories on the basis of the scores they obtained on the variable of well-being.

- Adolescents with low well-being.

- Adolescents with average well-being.

- Adolescents with high well-being.

For the classification of adolescents in the categories of high, average and low well-being, the classificatory scores given in the well-being scale by Singh and Gupta were used. As per the scale, the group of adolescents whose scores on the well-being scale were between 176-250 was termed as the group with high well-being. The group of adolescents whose scores on the well-being scale were between 125-175 was termed as the group with average well-being. The group of adolescents whose scores on the well-being scale were between 50-124 was termed as the group with low well-being.

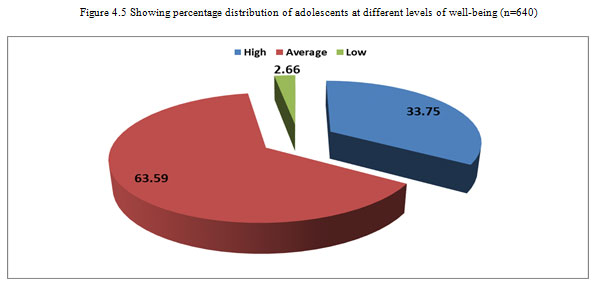

Table 4.5: Showing percentage distribution of adolescents at different levels of well-being (n=640)

| Category | Number of Adolescents | Percentage |

| High | 216 | 33.75 |

| Average | 407 | 63.59 |

| Low | 17 | 2.66 |

| Total | 640 | 100 |

|

Figure 4.5: Showing percentage distribution of adolescents at different levels of well-being (n=640) |

Table 4.5 and Fig. 4.5 shows that out of total 640 adolescents, 216 adolescents i.e. 33.75% of adolescents have high well-being, 407 adolescents i.e. 63.59% have average level of well-being and only 17 i.e. 2.66% have low level of well-being.

The distribution clearly indicates that majority of adolescents have average level of well-being. A substantial percentage of adolescents possess high well-being as well. However, a very small percentage of adolescents experience low well-being.

Percentages of adolescents depicting different levels i.e. high, average and low levels of well-being were also calculated for the following group of adolescents:

- Group of Adolescent Boys

- Group of Adolescent Girls

- Group of Rural Adolescents

- Group of Urban Adolescents

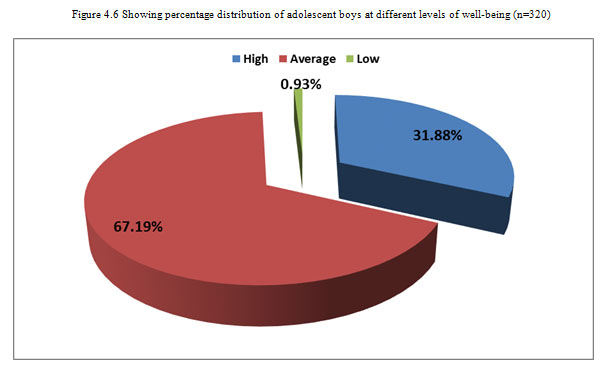

Table 4.6: Showing percentage distribution of adolescent boys at different levels of well-being (n=320)

| Category | Number of Adolescent Boys | Percentage |

| High | 102 | 31.88 |

| Average | 215 | 67.19 |

| Low | 3 | 0.93 |

| Total | 320 | 100 |

|

Figure 4.6: Showing percentage distribution of adolescent boys at different levels of well-being (n=320) |

Table 4.6 and Fig. 4.6 shows that out of total 320 adolescent boys, 102 adolescents i.e. 31.88% of adolescent boys have high well-being, 215 adolescent boys i.e. 67.19% have average level of well-being and only 3 i.e. 0.93% have low level of well-being.

The distribution clearly indicates that majority of adolescent boys have average level of well-being. A substantial percentage of adolescent boys possess high well-being as well. However a very small percentage of adolescent boys experience low well-being.

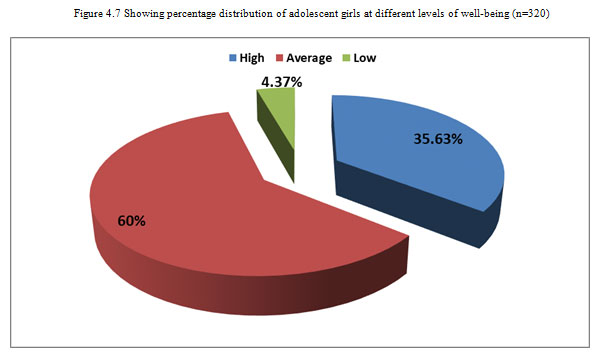

Table 4.7: Showing percentage distribution of adolescent girls at different levels of well-being (n=320)

| Category | Number of Adolescent Girls | Percentage |

| High | 114 | 35.63 |

| Average | 192 | 60 |

| Low | 14 | 4.37 |

| Total | 320 | 100 |

|

Figure 4.7: Showing percentage distribution of adolescent girls at different levels of well-being (n=320) |

Table 4.7 and Fig. 4.7 shows that out of total 320 adolescent girls, 114 adolescents i.e. 35.63% of adolescent girls have high well-being, 192 adolescent girls i.e. 60% have average level of well-being and only 14 i.e. 4.37% have low level of well-being.

The distribution clearly indicates that majority of adolescent girls have average level of well-being. A substantial percentage of adolescent girls possess high well-being as well. However a very small percentage of adolescent girls experience low well-being.

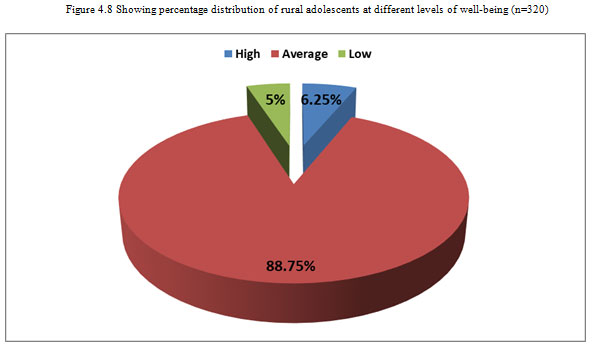

Table 4.8: Showing Percentage Distribution of Rural Adolescents at Different Levels of Well-being (N=320)

| Category | Number of Rural Adolescents | Percentage |

| High | 20 | 6.25 |

| Average | 284 | 88.75 |

| Low | 16 | 5 |

| Total | 320 | 100 |

|

Figure 4.8: Showing percentage distribution of rural adolescents at different levels of well-being (n=320) |

Table 4.8 and Fig. 4.8 shows that out of total 320 rural adolescents, 20 adolescents i.e. 6.25% of rural adolescents have high well-being, 284 rural adolescents i.e. 88.75% have average level of well-being and only 16 i.e. 5% have low level of well-being.

The distribution clearly indicates that majority of rural adolescents have average level of well-being. A However only a small percentage of rural adolescents experience high as well as low well-being.

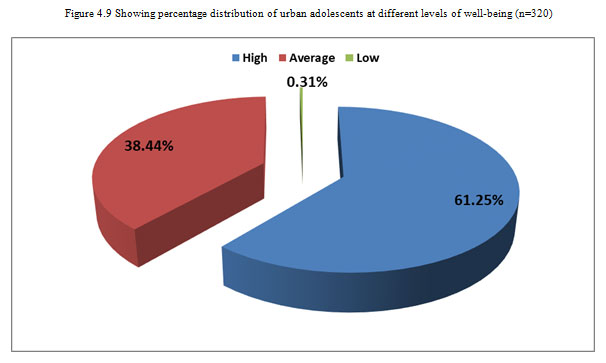

Table 4.9: Showing percentage distribution of urban adolescents at different levels of well-being (n=320)

| Category | Number of Urban Adolescents | Percentage |

| High | 196 | 61.25 |

| Average | 123 | 38.44 |

| Low | 1 | 0.31 |

| Total | 320 | 100 |

|

Figure 4.9: Showing percentage distribution of urban adolescents at different levels of well-being (n=320) |

Table 4.9 and Fig. 4.9 shows that out of total 320 urban adolescents, 196 adolescents i.e. 61.25% of urban adolescents have high well-being, 123 urban adolescents i.e. 38.44% have average level of well-being and only 1 i.e. 0.31% have low level of well-being. The distribution clearly indicates that majority of urban adolescents have high level of well-being. A substantial percentage of urban adolescents possess average well-being as well. However negligible percentage of urban adolescents experience low well-being.

Results and Discussion

The results of the study have implications for policy makers, parents and various social groups dealing with training of adolescents. Better understanding of the adolescent psychological problems and their early identification is need of the hour and the best way to a healthy society. Implications of this study can be carried forward into educational as well as counselling settings.The current study was conducted to assess the levels of psychological well-being among adolescents which revealed that out of total 640 adolescents, 216 adolescents i.e. 33.75% of adolescents have high well-being, 407 adolescents i.e. 63.59% have average level of well-being and only 17 i.e. 2.66% have low level of well-being A majority of adolescent boys and girls have average level of well-being. Majority of rural adolescents have average and majority of urban adolescents have high level of well-being. There can be several plausible reasons for the said results. Although, it is not possible to work out all the possible reasons, yet, it can be easily noted that life in urban areas is far more multifaceted than life in rural areas. There is better exposure for adolescents in urban areas than in rural areas. Urban environment has a more stimulating effect on learning and social interaction. Urban adolescents are more independent and are allowed to deal with their problems themselves. So they are better able to face the life situations and challenges. The adolescents from the rural perspectives are under intense pressure to act like adults. They are under social restrictions and they are not able to pursue their interest due to these restrictions and are expected to behave in an ideal manner as the social and cultural setups of villages expect them to be. Childhood spam is short for them. Thus they easily get affected by the physiological and psychological changes occurring during this period.

The study highlights the need to take some action in the educational scenario prevalent in rural areas as rural adolescents show lower level of well-being as compared to urban adolescents. The fact cannot be ruled out that majority of the population of India resides in rural areas and low well- being among rural adolescents will seriously affect our national development. For this purpose, suitable research works need to be initiated so that the real causes of the low well-being among rural adolescents can be identified and rural adolescents be helped accordingly.

References

Casas, F., Coenders, G., & Pascual, S. (2000). Subjective well-being and socially risky behaviors of youth. Paper presented at Conference International Society of Quality of Life Studies, Girona, Spain.

Diener, E., Suh, M., Lucas, E., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Essen E. V., & Martensson, F. (2014). Young adults’ use of food as a self-therapeutic intervention. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health Well-being. doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.23000

Easow R. J., & Ghorpade, P. (2017). Level of psychological well-being among adolescents in a selected high School at Tumkur. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS). 6 (4), 74-78.

Forgeard, M. J. C., Jayawickreme, E., Kern, M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1), 79–106. doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v1i1.15

Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60(7), 678–686.

Jovic-Varnes, A., Jankovic, J., Vasic, V., Jankovic, S. (2011). Self-perceived health and psychological well-being among Serbian school children and adolescents: data from national health survey. Central European Journal of Medicine, 6(4), 400-406. Retrieved fromhttp://iproxy.inflibnet.ac.in:2610/article/10.2478/s11536-011-0035-z

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.) (1999). Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3-25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Karatzias , A., Chouliara, Z., Power, K., & Swanson V. (2006). Predicting general well-being from self esteem and affectivity: An exploratory study with Scottish adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1143-1151.

Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 1007-1022. doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007.

Khan, A. (2013). Predictors of positive psychological strengths and subjective well-being among north Indian adolescents: Role of mentoring and educational encouragement. Social Indicators Research, 114(3), 1285-1293.

Kunhikrishnan K., & Stephen, P. S. (1992). Locus of control and sense of general well-being, Psychological studies, 37(1), 73-75.

Lekes, N., Gingras, I., Philippe, F. L., Koestner, R., & Fang, J. (2010). Parental autonomy-support, intrinsic life goals, and well-being among adolescents in China and North America. Journal of Youth and adolescence. 39(8), 858-869. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9451-7

Mahajan, N., & Sharma, S. (2008). Stress and storm in adolescence, Indian Journal of Psychometry and Education, 39(2), 204-207.

Pathak, R., Sharma, R. C., Parvan, U. C. , & Gupta, B P., Ojha, R. K., & Goel, N. (2011). Behavioural and emotional problems in school going adolescents. The Australasian Medical Journal. 4. 15-21. 10.4066/AMJ.2011.464.

Rathi, N., & Rastogi, R. (2007). Meaning in life and psychological well-being in pre- adolescents and adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 33 (1) 31-38.

Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(4), 719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Schlabach, S. (2013). The importance of family, race, and gender for multiracial adolescent well-being. Family Relations. 62(1) 154-174.

Seaton, T. K., Yip, T. (2009). School and neighborhood contexts, perceptions of racial discrimination, and psychological well-being among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(2), 153-163.

Sehgal, M., & Sharma, A. (1998). A study of gender differences in health well-being, stress and coping. Asian journal of psychology and Education, 30 (5-6), 22-27.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish – A new understanding of happiness and well-being – and how to achieve them. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Sharma, R., Grover, V. L., & Chaturvedi, S. (2008). Suicidal behavior amongst adolescent students in south Delhi. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 50 (1), 656-62.

Singh, J. & Gupta, A. (2001). Well-being scale. Recent Researches in Education and Psychology, 6.

Stratham, J., & Chase, E. (2010). Childhood wellbeing: A brief overview. Loughborough: Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre.

Thomas, J. (2009). Working paper: Current measures and the challenges of measuring children’s wellbeing. Newport: Office for National Statistics.

Vandeleur, C.L., Jeanpretre N., Perrez, M., Schoebi D., & Murry, V. M. (2009). Cohesion, satisfaction with family bonds and emotional well-being in families with adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71 (5), 1205-1219.

Vera, E. M., Vacek, K., Blackmon, S., Coyle, L., Gomez, K., Jorgenson, K.,…Steele, J. C, (2011). Subjective well-being in urban, ethnically diverse adolescents the role of stress and coping. Youth and Society, 20(10), 1-17. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com

Viejo, C., Gómez-López, M., Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2018). Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being: A Multidimensional Measure. International Journal Environment Research Public Health 15, 23-25.

Walsh, S. D. Harel-Fisch, Y., & Fogel-Grinvald, H. (2010). Parents, teachers and peer relations as predictors of risk behaviors and mental well-being among immigrant and Israeli born adolescents. Social Science & Medicine,70, 976–984. Retrieved from www.elsevier.com

World Health Organisation. (2012). Developing national quality standards for adolescent friendly health services Geneva: WHO.