1Department of Prosthodontics, Margalla Institute of Health Sciences, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

2Department of Pre-Clinical Dentistry, Army Medical College, NUMS, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

3Assistant Professor Department of Prosthetic Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,

4Professor, Department of Prosthetic Dental Sciences, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,

5Department of Prosthodontics, de’Montmorency College of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan

6Dept. of Orthodontics, Islamic International Dental College, Islamabad Pakistan

7Department of Prosthodontics, Armed Forces Institute of Dentistry, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Corresponding author email: syhabib@ksu.edu.sa

Article Publishing History

Received: 07/12/2020

Accepted After Revision: 24/03/2021

Violence at work affects the health and safety of dental healthcare workers and studies related to the aggression of patients and their attendants towards dental healthcare staff are scarce. The aim of the present cross sectional study was to assess the frequency and causes of aggressive behavior of patients and their attendants encountered by dental healthcare workers in tertiary care institutes and independent private practices. A self-administered questionnaire consisting of 12 close-ended questions was used to collect data from 286 dentists, postgraduate residents, consultants and assistants. Descriptive statistics were calculated and post-stratification Chi-squared test was used to control effect of gender (P<0.05).

Majority (45.1%, n=129) of subjects reported encountering violent behavior at least once a week. Statistically significant difference was observed between frequency of violent behavior experienced by females and males, where females reported a higher frequency of such encounters in routine (P<0.001) The most commonly encountered aggressive behavior was the use of harsh tone or shouting reported by 73.4% of participants. Most significant reason for aggressive behavior was mishandling at the reception (n=143; 50%) followed by unrealistic expectations of patients (n=106; 37.1%) and culture of dominating healthcare professionals (n=99; 34.6%) as well as socially or professionally influential patients who try to influence the doctor (n=99; 34.6%). Dental healthcare workers frequently encounter aggressive behavior from patients and their attendants. Females are targeted significantly more than males (P<0.001).

Dentists; Dental Professionals; Occupational health; Patient Aggression; Workplace violence.

Hassan S. H, Aslam A, Alqahtani A. S, Habib S. R, Akram M, Zulfiqar K, Sharif M. Patient-Attendant Aggression Towards Dental Professionals: a Survey Based Analysis. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2021;14(1).

Hassan S. H, Aslam A, Alqahtani A. S, Habib S. R, Akram M, Zulfiqar K, Sharif M. Patient-Attendant Aggression Towards Dental Professionals: a Survey Based Analysis. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2021;14(1). Available from: <a href=”https://bit.ly/3rBJqaS”>https://bit.ly/3rBJqaS</a>

Copyright © Hassan et al., This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) https://creativecommns.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use distribution and reproduction in any medium, provide the original author and source are credited.

INTRODUCTION

Violence at work is one of the major deterrents affecting “health and safety” of workers in all sorts of occupations (Pouryaghoub et al., 2017). Aggressive behavior of patients and their attendants towards dental health care providers is an increasingly significant yet an under reported problem (Franz et al., 2010; Duxbury & Whittington., 2005; Cooper & Swanson., 2002). The term ‘aggression’ is used to refer to hostile behavior of varying intensity that leads to harm irrespective of the intent of the aggressor (Edward et al., 2014). Even though the term violence differs in its literal context from aggression these two terms have been used interchangeably in literature to describe workplace aggression or violence in health care settings. The absence of a universally accepted operational definition of workplace aggression/violence also makes it difficult to draw comparisons between studies from different cultures, regions and specialties (Imran et al., 2013; Hills, 2018, Rhoades et al 2020).

Emergency departments, psychiatric wards and geriatric units apparently have the highest frequency of aggression that have been reported in health care settings. Healthcare settings as mentioned earlier and certain healthcare workers like paramedical staff in emergency department, ambulance staff and nurses are more prone to experience aggression perpetrated by the patients, their attendants or their visitors (However, aggression in healthcare settings is more widespread and needs to be examined within the context of that particular domain of healthcare, cultural/regional specificity and other associated factors, (Aydin et al. 2009 Llor- Ambesh, 2016, Esteban et al 2017 and Lee et al., 2020).

There is a significant gap in literature as far as reporting of aggression of patients and their attendants towards dental health care staff is concerned. There are only a few reports which have studied this phenomenon in dental practice (Pemberton et al., 2000). The aim of this study was to assess workplace aggression against dentists and dental assistants working in tertiary care dental hospitals and private dental practices in the twin cities of Rawalpindi & Islamabad Pakistan. More specifically this study sought to examine the frequency, the factors associated with aggression experienced by dental staff, the implications of such behavior and the suggestions for minimizing such behavior.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was designed and conducted from August 2019 to December 2019. Approval from ethical review committee of Armed Forces Institute of Dentistry, Rawalpindi, Pakistan was sought (Approval # ERC/2019/OA-22). Sample size was calculated using WHO sample size calculator. Keeping confidence level (1-α) at 95%, absolute precision (d) at 0.0539 and anticipated population proportion (P) at 0.319, (Azodo et al., 2011) a sample size of 286 was calculated. General dentists, postgraduate residents in any dental specialty, consultants from all dental specialties and dental surgery assistants who were willing to participate were included in the study.

A self-administered questionnaire consisting of 12 close-ended questions was used as the data collection tool. The questionnaire was first pilot – tested to ensure its validity, reliability and relevance. The first part of the questionnaire aimed to collect the demographics including age, gender, practice status and years of experience. In the 2nd part, questions were designed to assess the frequency of aggressive behavior encountered, probable causes of such a behavior and its effect on dental professionals’ efficiency. Data was analyzed in SPSS 24. Descriptive statistics were calculated. Post-stratification Chi-squared test was used to control effect of gender. P<0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The study comprised of 286 study subjects and out of these, 35% (n=100) were male and 65% (n=78) were females. 8.4% subjects (n=24) were consultants in their fields, 36% were residents (n=103), 31.5% (n=90) were interns or house officers, 10.1% were general dentists (n=29), and 14% (n=40) were dental surgery assistants. Majority (46.5%, n=133) of the subjects reported a clinical experience of less than 2 years, while only 7.3% (n=21) had a clinical experience of more than 10 years. Most of the subjects (31.5%, n=90) reported seeing an average of 6-10 patients per day while a smaller percentage (14.7%, n=42) saw more than 20 patients daily. In majority of the cases (69.6%, n=199) dental practices accepted both walk-in patients as well as appointed patients. Only 22% (n=63) practices were solely appointment-based. Study subjects reported varying frequency of aggressive behavior they faced at work, with a good majority (45.1%, n=129) encountering such behavior at least once a week.

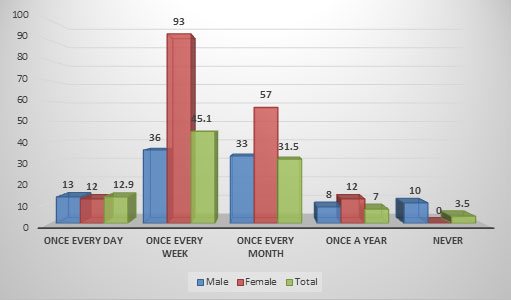

A statistically significant difference was observed between frequency of violent behavior experienced by females and males, where females reported a higher frequency of such encounters in routine (P<0.001) (Figure 1). The most commonly encountered aggressive behavior was the use of harsh tone or shouting reported by 73.4% of the subjects followed by verbal abuse, swearing and insult reported by 25.5% while physical assault was reported by 1.09% of the study participants, which is quite alarming.

Figure 1: Frequency of aggressive behavior of patients/attendants faced by study subjects.

Half of the study subjects (50%, n=143) reported that their manager at work was appropriately trained/capable of managing any patient or attendant with an aggressive attitude. In contrast, 79.4% of the respondents reported that they themselves had not received any formal training in managing aggressively charged or overly emotional patients and 85.7% stated no counselling services were available to them following any undesirable encounter with a patient, resulting in an emotional setback for the dental staff (Table 1).

Table 1: Response to questions about formal training to manage aggressive behaviour.

| Question | Response | ||

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Can’t Say (%) | |

| Do you think that your reception or clinic manager is appropriately trained/capable of managing any patient or attendant with an aggressive attitude? | 143 (50) | 89 (31.1) | 54 (18.9) |

| Do you have any formal training in managing aggressively charged or overly emotional patients? | 59 (20.6) | 227 (79.4) | – |

| Are there any counselling services available to you following any untoward happening where the patient or their attendants have behaved aggressively, or their behavior might have resulted in an emotional setback for you? | 41 (14.3) | 245 (85.7) | – |

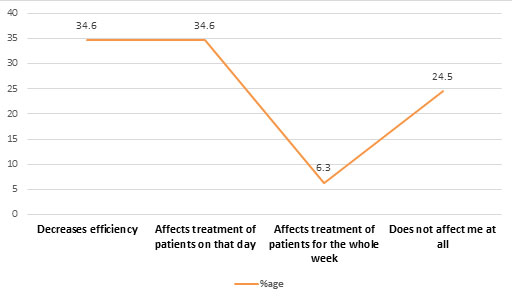

Question regarding effect of patient’s aggressive behavior on dental staff’s efficiency received varying responses (Figure 2). An equal number of respondents (n=99 each, 34.6% each) reported that such a disturbing encounter with patient decreased their efficiency at work and affected the treatment of patients on that particular day while 24.5% (n=70) believed that they were not affected by such encounters.

Figure 2: Effect of patient’s aggressive behavior on dentist’s efficiency.

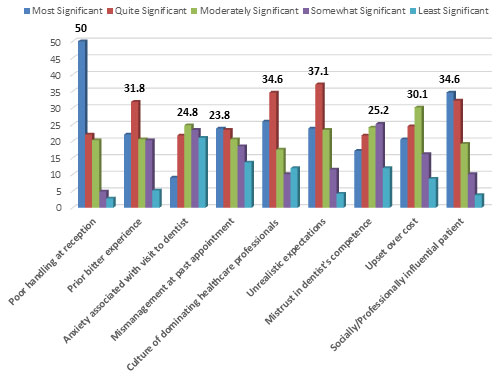

Participating dental health care providers were asked to grade the most probable reasons for patients behaving aggressively or getting overly emotional in the dental office, and the results are highlighted in Figure 3. The factor regarded as most significant reason for aggressive behavior was mishandling at the reception (n=143, 50%) followed by unrealistic expectations of patients (n=, 37.1%) and culture of dominating healthcare professionals (n=99, 34.6%) as well as socially or professionally influential patients who try to influence the doctor (n=99, 34.6%).

Figure 3: Probable reasons of patients’ aggressive behavior towards dentists.

Majority (n=103, 36%) of the study subjects believed that both genders were equally liable to show aggressive behavior, and 60.5% (n=173) believed that patients falling in the age group 41 – 60 years were more prone to showing aggressive behavior (Table 2). About 90.2% (n=258) dentists reported that ethnicity of patients did not affect their tendency to show aggressive behavior.

Table 2. Age-group more prone to aggressive behaviour among patients.

| Age Group | Frequency | Percent |

| <20 years | 6 | 2.1 |

| 21 – 40 years | 84 | 29.4 |

| 41 – 60 years | 173 | 60.5 |

| >60 years | 23 | 8 |

The current study assembled data on aggressive behavior of patients and their attendants towards dental healthcare personnel. The targeted participants were the dental healthcare personal working in different positions and settings of dental clinics/hospitals. The obtained information can be helpful in designing and planning future strategies regarding management of the aggression of the patients and their attendants in the dental settings. Violent and aggressive behavior of patients or their attendants against dental healthcare professionals poses a serious threat to health and safety at workplace. It not only makes health professionals anxious and tensed, but also diminishes their ability to deliver optimal care to other patients. Very few studies have been published that report the frequency of undesirable encounters of the dental team with patients and their attendants.

In the present study, majority (45.1%) of the respondents reported facing aggressive behavior at work at least once a week. A study done in UK on postgraduate hospital dentists revealed that 60% dentists had experienced bullying behavior in the last one year (Steadman et al., 2009). This, however, not only included bullying by patients and their attendants but by colleagues, seniors, supervisors and managers. A considerably lower prevalence has been reported by Azodo et al (2011), where majority of the dental health professionals had experienced aggressive behavior only once in the last 12 months. Another study done in Nigeria reported a prevalence of 21.5% violence against dentists and doctors (Abodunrin et al., 2014).

Frequency of violence or aggression directed against females was significantly higher than against male dental healthcare personnel (P<0.001). Although studies have documented female medical healthcare workers as the more common victims of aggressive behavior, Aydin et al., 2009; Child and Mentes, 2010, Pouryaghoub et al., 2017; Llor-Esteban et al., 2017) no gender predilection in violence against dentists has been reported (Azodo et al., 2011; Steadman et al., 2009; Abodunrin et al., 2014).In the present study, most of the participants (50%) believed that the most significant reason leading to aggressive behavior of patients was mishandling at the reception/long waiting time followed by patient’s unrealistic expectations (37.1%).

Interestingly, 50% of the study subjects also believed that their reception manager was not appropriately trained to manage aggressive patients. Similar results have been reported by Azodo et al (2011) and Abodunrin et al (2014), where long waiting time or not being treated on time was cited as the most frequent reason resulting in patient aggression. The aggressive behavior of the patients and their attendants due to long waiting time can further be explained and related to the variations in the complexity and severity of the different treatment modalities in the dental clinics (Tuominen & Eriksson, 2012).

These variations make it difficult if not impossible to predict exactly the time duration required for completion of the ongoing dental treatments. Besides there is no universal agreement and no studies reported on the appropriate duration of the various treatments provided in the dental clinics (Jamali et al., 2018). Although some researchers suggested different treatment durations for the children of different ages (Aminabadi et al., 2009). However, these suggestions are based on arbitrary assumptions and cannot be generalized and applied for other treatment modalities.Two interesting factors resulting in aggressive behavior of patients and their attendants were revealed in this study. These included i. a culture of trying to dominate the healthcare professionals and, ii. patients with social/professional hierarchy who can exercise influence and authority.

These factors are more prevalent in the Indian subcontinent i.e. India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Srilanka. Such behavior is perpetuated mainly due to lack of “legal provisions and standards” in these countries that may ensure safety of healthcare workers (Ambesh, 2016; Sharma et al., 2019). Negative behavior of patients or their attendants, even the use of harsh tone, tends to take a toll on dentist’s efficiency. In the present study, 74.5% dental health care providers reported being affected by patient’s aggression in one way or another affecting dentists’ efficiency and treatment of succeeding patients, while only 24.5% reported not being affected at all. In contrast, 43.2% dental healthcare workers reported feeling “no impact” of patients’ behavior in a Nigerian study (Azodo et al., 2011). Results of the present study highlight a need to formulate and implement policy ensuring a health and safety culture for dental healthcare workers.

Healthcare workers need to be ensured of safety and should be encouraged while reporting patients’ misbehavior, and records must be maintained of such incidents and any ensuing action. Healthcare workers need to be educated how to exercise their rights in order to protect themselves and their practice (Cashmore et al., 2012). There is also a need to enhance awareness of the general population regarding administration of health facilities especially dental care. Moreover, culture of trying to influence health professionals or the habit to exercise influence owing to one’s social status needs to be strongly discouraged. At the moment, there are approximately 25000 registered dental surgeons for a population of 220 million in Pakistan and all those registered are not involved in clinical practice. It is quite evident that practicing dentists are greatly overburdened, are underpaid and in addition, have to face patients’ or their attendant’s aggressive behavior.

Healthcare facilities need to be improved, with delivery of oral healthcare facilities even in rural areas.The limitation of this study are those inherently associated with survey-based studies. Data derived from these studies may have an element of bias since they are subjective and depend on the truthfulness of the participant. Although the sample size was sufficient, yet the representation of dental surgery staff was inadequate. Also, dental personnel working in government setups where aggression towards healthcare workers and harassment is frequently reported, were not targeted as they were difficult to approach. Future studies should be aimed at including a greater number of healthcare workers from public sector and with an adequate representation of dental surgery assistants.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of this study, it is concluded that dental healthcare workers in Rawalpindi/Islamabad frequently encounter aggressive behavior from patients and their attendants. Females were targeted significantly more than males (P<0.001). The most common reason of misconduct of patients was mismanagement at reception especially due to long waiting time. Such undesirable encounters with patients decreased efficiency of dentists as well as affected treatment of following patients.

REFERENCES

Abodunrin OL, Adeoye OA, Adeomi AA, Akande TM. (2014) Prevalence and forms of violence against health care professionals in a South-Western city, Nigeria. Sky J Med Med Sci 2(8):67-72.

Ambesh P.(2016) Violence against doctors in the Indian subcontinent: a rising bane. Indian Heart J 68(5):749-50.

Aminabadi NA, Oskouei SG, Farahani RM.(2009) Dental treatment duration as an indicator of the behavior of 3-to 9-year-old pediatric patients in clinical dental settings. J Contemp Dent Pract 10(5):E025-32.

Aydin B, Kartal M, Midik O, Buyukakkus A. (2009)Violence against general practitioners in Turkey. J Interpers Violence 24(12):1980-5.

Azodo CC, Ezeja EB, Ehikhamenor EE.(2011) Occupational violence against dental professionals in southern Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 11(3):486-92.

Cashmore AW, Indig D, Hampton SE, Hegney DG, Jalaludin BB. (2012) Workplace violence in a large correctional health service in New South Wales, Australia: a retrospective review of incident management records. BMC Health Serv Res 12:245-54.

Child RH, Mentes JC. (2010) Violence against women: the phenomenon of workplace violence against nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31(2):89-95.

Cooper C, Swanson N. (2002) Workplace violence in the health sector: State of the art. Geneva: Organización Internacional de Trabajo, Organización Mundial de la Salud, Consejo Internacional de Enfermeras Internacional de Servicios Públicos.; 2002.

Duxbury J, Whittington R. (2005) Causes and management of patient aggression and violence: staff and patient perspectives. J Adv Nurs 50(5):469-78.

Edward K, Ousey K, Warelow P, Lui S.(2014) Nursing and aggression in the workplace: a systematic review. Br J Nurs 23(12):653-9.

Franz S, Zeh A, Schablon A, Kuhnert S, Nienhaus A. (2010) Aggression and violence against health care workers in Germany-a cross sectional retrospective survey. BMC Health Serv Res 10(1):51-8.

Hills DJ.(2018) Defining and classifying aggression and violence in health care work. Collegian 25(6):607-12.

Imran N, Pervez MH, Farooq R, Asghar AR.(2013) Aggression and violence towards medical doctors and nurses in a public health care facility in Lahore, Pakistan: A preliminary investigation. Khyber Med Univ J 5(4):179-84.

Jamali Z, Najafpour E, Ebrahim Adhami Z, Sighari Deljavan A, Aminabadi NA, Shirazi S. (2018) Does the length of dental procedure influence children’s behavior during and after treatment? A systematic review and critical appraisal. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects 12(1):68-76.

Lee HL, Han CY, Redley B, Lin CC, Lee MY, Chang W.(2020) Workplace violence against emergency nurses in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. J Emerg Nurs 46(1):66-71.

Llor-Esteban B, Sánchez-Muñoz M, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Jiménez-Barbero JA.(2017) User violence towards nursing professionals in mental health services and emergency units. Eur J Psychol Appl Leg Context 9(1):33-40.

Pemberton M, Atherton G, Thornhill M.(2000) Violence and aggression at work. Br Dent J 189:409-10.

Pouryaghoub G, Mehrdad R, Alirezaei P.(2017) Workplace violence in medical specialty training settings in Iran: a cross-sectional study. Int J Occup Hyg 9(1):15-20.

Rhoades KA Heyman RE Eddy JM et al (2020) Patient Aggression towards dentists J Amer Dental Association 151 : 10, 764-769 PMID 32979955

Sharma S, Shrimali V, Thakkar H, Upadhyay S, Varma A, Pandit N, et al.(2019) A study on violence against doctors in selected cities of Gujarat. Med J DY Patil Vidyapeeth 2(347-51).

Steadman L, Quine L, Jack K, Felix DH, Waumsley J.(2009) Experience of workplace bullying behaviours in postgraduate hospital dentists: questionnaire survey. Br Dent J 207:379-80.

Tuominen R, Eriksson AL.(2012) Patient experiences during waiting time for dental treatment. Acta Odontol Scand 70(1):21-6.