1Pediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics Department, College of Dentistry, King

Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2Dental Intern, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

3Dental Intern, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

4Dental Intern, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

5Dental GP, College of Dentistry, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Article Publishing History

Received: 03/04/2021

Accepted After Revision: 28/06/2021

Sports is considered as one of the most common reasons of the orofacial trauma in school-age children. Sports-related mouth guards minimize the risk of injuries in school-age children. The aim of this study is to assess the knowledge of parents about the use of mouth guards by their children during different activities. Cross-sectional survey composed of a questionnaire with 21 multiple choice questions was randomly distributed to 319 parents who have school-age children (7-12 years old). Out of the 319 subjects responded to this study, there were 77.4% mothers. The distribution of characteristics of children shows 56.1% were male. About 65.8% of the children play sports. The maximum number of children (38.3%) had facial bruising followed by other type of injuries.

The primary baby teeth were affected in the injury for 38.3% of children. Only 16 (34%) of these injured children had visited the dentist. The knowledge towards mouth guard was assessed among the parents, where only 17.9% of them were familiar with sports mouth guard. A small number 5(1.6%) of them responded that their children use mouth guard during sports. Those who did not use mouth guard, 248(81.3%) had responded as “lack of information about it” as the main reason and 43.9% of them were aware that mouth guard can prevent oral/dental injury. In conclusion there is a lack of parental knowledge regarding the importance of use of mouth guards in reducing dental injuries in school-age children. Professional and parents should be educated regarding the use of mouth guards during activities.

Knowledge, Mouthguard, Parent, Sports-Related, Shool-Age

Hafiz Z, Almaleh B, Alsaban R, Alzahrani S, Alzahrani S. Parental Knowledge on Using Sports-Related Mouth-guards in School-age Saudi Children. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2021;14(3).

Hafiz Z, Almaleh B, Alsaban R, Alzahrani S, Alzahrani S. Parental Knowledge on Using Sports-Related Mouth-guards in School-age Saudi Children. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2021;14(3). Available from: <a href=”https://bit.ly/3AzzP8W”>https://bit.ly/3AzzP8W</a>

Copyright © Hafiz et al., This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) https://creativecommns.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use distribution and reproduction in any medium, provide the original author and source are credited.

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic dental injuries are common in pre-school, school-age and young adults making up 5% of all injuries of which the patients seek treatment for (Petersson et al., 1997; Andreasen et al., 2007). One-third of all dental injuries found to be related to sport activities (Nowjack & Gift, 1996; Collins et al., 2015). The most common type of injuries of the orofacial area is the dentofacial injuries (Tuna & Ozel, 2014). Dental injuries range from concussions to more serious injuries of the oral cavity involving surrounding tooth structures (Al-Obaida, 2010).

Avulsion, which is the total loss of the tooth out of its socket, is the most serious and crucial type of all injuries to the oral cavity. It represents 1-16% of dental trauma in which the highest incidence found in children 7-11 years old, with the maxillary central incisor being 80% the most affected tooth (Al-Shamiri et al., 2015; Goswami et al., 2017, Borris et al., 2019, Li et al., 2021).

The primary teeth injuries showed a prevalence that varies from 11% to 30 %, while the permanent teeth range between 2.6 % – 50 % (Tuna & Ozel, 2014). Moreover, children who are encouraged to participate in contact sports are at great risk of dental injuries (Tuna & Ozel, 2014; Collins et al., 2015). The type of dental trauma is affected by multiple factors, including the force direction, the impaction of the force, and the resilience of the impacting object (Collins et al., 2015). Avulsed teeth, TMJ dysfunction, subluxations, lip laceration, crown fracture, extrusion, intrusion, alveolar bone fracture, and root fracture are common consequences to trauma (Petersson et al., 1997; Newsome et al., 2001; Collins et al., 2015).

Full-contact sports such as boxing and football are not the only risks for dental injuries, it also can occur in other sports such as in basketball or baseball (Collins et al., 2015). Among various sports, softball, basketball, and baseball have a relatively high risk of dental injury with low prevalence of mouth guard use. Complications of dentofacial injuries can result in dental crowding, abscesses, and failure of eruption of the permanent teeth, spacing, and hypoplasia (Tuna & Ozel, 2014). Thus, it is important to raise the awareness of sports-related dental damage risk and emphasize on the role of dentists to prevent such accidents by recommending the use of mouthguards in all sorts of sports (Tuna & Ozel, 2014; Green, 2017, Ramakrishnan et al., 2019, Al-Habib, 2019, Ayesha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2021).

The literature supports the use of mouth guards in reducing and preventing dental trauma (Onyeaso, 2004). Mouth guards, also called a gum shield, defined as “a resilient device or appliance placed inside the mouth (or inside and outside), to reduce mouth injuries, particularly to teeth and surrounding structures” (Pribble et al., 2004). Custom-made well-fitting mouth guards which are fabricated by the dentist have shown to deliver the best protection (Mekayarajjananonth et al., 1999). More than one visit to the dentist is needed to receive the custom-made well-fitting mouth guard. The process includes taking dental impression, study models, and laboratory construction steps (Westerman et al., 2002).

In addition, a stock mouth guard is a preformed thermoplastic tray that loosely fits over the teeth. They can be found in sports stores and are used without modification. Nevertheless, they provide limited protection (ADA, 2006). Mouth-formed ‘boil and bite’ mouth guards can also be bought from the stores. However, they are molded after being merged in hot water and softened to fit the individual’s mouth by pressure from the fingers, cheeks and tongue having a higher protection than stock mouth guards (Westerman et al., 2002 Ramakrishnan et al., 2019, Al-Habib, 2019, Ayesha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2021).

Pribble et al. (2004) studied the factors that influence parental perceptions regarding mandatory mouthguard use in competitive youth soccer and found that few athletes wear mouthguards during the sport activities and recommended to make more efforts by health specialists and sport organizations to educate the parents about orofacial injuries and mouthguard use. O’ Malley et al.

(2012) made a survey to assess school and sports club policy on mouthguard use in sport, they concluded that the dental profession and individual practitioners should encourage the use of mouthguard for children during sport and be responsible for the development of policies in schools and sporting organizations. Moreover, Quaranta et al. (2014) conducted their study to assess the knowledge of the parents of the primary school children to plan corrective actions and the results showed that parents lack awareness, knowledge and skills to prevent or manage dental trauma.

In addition, Green (2017) did a meta-analyses study of oral injuries and reported that individuals who don’t use mouthguards have a higher incidence by 1.6-1.9 times compared with those who use it. Although this form of preventive device is easy to use, available, effective and inexpensive it has been underutilized (Collins et al., 2015). Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess parental knowledge regarding the use of mouth guard during sport activities among school-age children in Riyadh city.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A cross sectional study was conducted to assess parental knowledge regarding the use of mouth guard during various sport activities among their school-age children (7-12 years old) in Riyadh city. This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) (no. E-19-4353) of King Saud University in Riyadh, KSA. Three hundred and nineteen participants were selected using stratified-cluster random sampling technique. The city of Riyadh was divided into 5 regions and parents were informed that their participation is voluntary in the study.

The questionnaire included questions about the children who were classified as Cl I or II status according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification. A power analysis was done to specify the appropriate sample size. To achieve a significance level at the 95th percentile confidence level and power of 80 percent, with 0.5 estimated effect size, the sample size was calculated to be 200 subjects.

A validated, self-report questionnaire containing 21 multiple-choice questions was distributed manually (hand-to-hand) to the parents in which each parent signed consent form declaring that their participation in this study is voluntary and their personal information will not be shared and only be used for study purposes. Furthermore, the purpose of the study was explained to the parents in an understandable language, as well, the questionnaire was written in their familiar language (Arabic). The questionnaire was divided into 3 main sections, the demographic data, the age of the child and his/her educational level, and knowledge, management and experience of the child with dental trauma.

The inclusion criteria are parents of Saudi, ASA Cl I and II, school-age (7-12 years old) children who live in Riyadh. Parents who have more than one child falling in the selected age group, the oldest child will be used as the index child for this study. Non-Saudi, medically compromised children, children not living in Riyadh, and less than 7 or more than 12 years old children will be excluded from this study. Moreover, a pilot study was performed and one of the authors (ZH) assessed the parental understanding of the questionnaire. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and chi-square test for association.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 version statistical software. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to describe the categorical variables. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to observe the association between categorical variables. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was used to report the statistical significance. Out of the 319 subjects responded to this study, there were 77.4% mothers, 90% of parents were in age group of 31-40 and >40 years, more than 50% of them had bachelor degree, 81.2% of them with middle level socio-economic status and about 50% of them had 4- 6 children. (Table 1)

Table 1. Distribution of Characteristics of Study subjects (n=319)

| Study variables | No. (%) |

| Parent who responded

Father Mother Age of parent (in years) 20-30 31-40 >40 Level of education Illiterate Elementary Intermediate Secondary Bachelor Higher Education

Socio-economic status Low Middle High Number of children 1-3 4-6 >6 |

72(22.6)

247(77.4) 33(10.3) 145(45.5) 141(44.2)

— — 10(3.1) 57(17.9) 215(67.4) 37(11.6) 10(3.1) 259(81.2) 50(15.7) 134(42) 157(49.2) 28(8.8) |

The distribution of characteristics of children shows 56.1% were male and their age was between 7 to 12 years and belongs to the grade between 2nd and 7th. (Table 2)

Table 2. Distribution of characteristics of Children

| Study variables | No. (%) |

| Gender

Male Female Age (in years) 7 8 9 10 11 12 Grade of Child(n=317) Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Seventh Other |

179(56.1)

140(43.9) 56(17.6) 34(10.7) 51(16) 51(16) 50(15.7) 77(24.1) 66(20.8) 46(14.5) 72(22.7) 53(16.7) 31(9.8) 26(8.2) 23(7.2) |

About 65.8% of the children play sports, in which 49.5% of them play Contact/collision (football, martial arts, wrestling, boxing), 19.1% of them play Limited contact/impact (basketball, cycling, gymnastics, skating, squash, volleyball). Only 35 (11%) of the total children had facial or dental injury during sports.

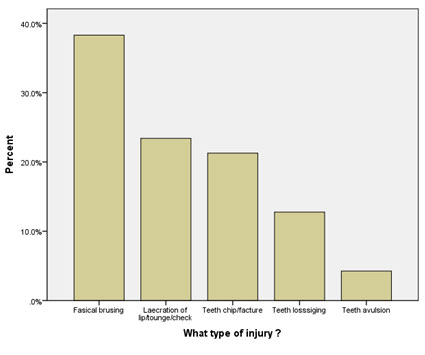

The type of injury was expressed as facial bruising, laceration of lip/tongue/cheek, teeth chip/fracture, teeth loosening and teeth avulsion (tooth/teeth completely fall out of the mouth), where the maximum number of children (38.3%) had facial bruising followed by other type of injuries (Fig. 1). The primary baby teeth were affected in the injury for 38.3% of children. Only 16 (34%) of these injured children had visited the dentist, in which 12 (26.1%) had visited immediately after the injury. (Table3)

Table 3. Distribution of variables related to Child dental trauma and its management

| Study variables | No. (%) |

| Do your child play sports?

Yes No Type of sport Contact/collision (football, martial arts, wrestling, boxing) Limited contact/impact (basketball, cycling, gymnastics, skating, squash, volleyball) Strenuous contact (tennis, weightlifting, swimming) Moderately strenuous contact (badminton, table tennis) Non strenuous contact (archery, golf) Other sports Did your child ever sustain any facial or dental injury during sports? Yes No I don’t know What type of injury? (n=47) Facial bruising Laceration of lip/tongue/cheek Teeth chip/fracture Teeth loosening Teeth avulsion (tooth/teeth completely fall out of the mouth) If you child has dental injury involving his/her teeth, which tooth/teeth was/were affected? (n=47) Primary/baby teeth Permanent/ adult teeth I don’t know Have you visited a dentist following the accident that involved his/her tooth/teeth? (n=47) Yes No I don’t remember If you visited the dentist after the accident, when did the visit take place? (n=46) Immediately after the accident One day after the accident During the first week of the accident After 1 month of the accident |

210(65.8)

109(34.2) 158(49.5) 61(19.1) 7(2.2) 17(5.3) 54(16.9) 35(11) 272(85.3) 12(3.8) 18(38.3) 11(23.4) 10(21.3) 6(12.8) 2(4.3) 18(38.3) 5(10.6) 24(5.1) 16(34) 13(27.7) 18(38.3)

12(26.1) 6(13) 10(21.7) 18(39.1) |

Figure 1: Types of Injuries

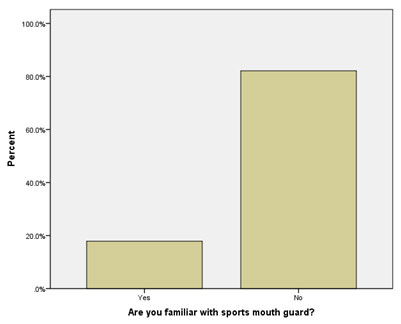

The knowledge towards mouth guard was assessed among the parents, where only 17.9% of them were familiar with sports mouth guard (Fig. 2). A small number 5(1.6%) of them responded that their children use mouth guard during sports. In these 5 responses, 3 of them mentioned about the use of commercial ready-made and 2 were used custom-made at the dentist office. Those who did not use mouth guard, 248(81.3%) had responded as “lack of information about it” as the reason followed by other reasons (it is expensive, it is uncomfortable, and it is not important). About 43.9% of them were aware that mouth guard can prevent oral/dental injury. Towards the use of mouth guard in future for their children, 64.3% of them had responded positively. (Table 4)

Table 4. Knowledge of about sports mouth guard

| Items related to knowledge | No. (%) |

| Are you familiar with sports mouth guard?

Yes No Does your child use mouth guard during sports? Yes No If your answer is yes to question 17, what type of mouth guard your child uses? (n=5) Custom-made at the dentist office Commercial ready-made (sports shop brand) If your answer is no to question 17, why are they not using it? (n=305) It is expensive It is uncomfortable It is not important lack of information about it Other

Do you think that mouth guards can prevent oral / dental injury? Yes No I don’t know Would you consider letting your child use it in the future? Yes No I don’t know |

57(17.9)

262(82.1) 5(1.6) 314(98.4) 2(40) 3(60) 3(1) 12(3.9) 14(4.6) 248(81.3) 28(9.2) 140(43.9) 20(6.3) 159(49.8) 205(64.3) 8(2.5) 106(332) |

Figure 2: Familiarity with Mouth guards

The association between characteristics of parents and their familiarity with mouth guard (Yes/No) shows no statistically significant association with the variables (parent, age of parent and socio-economic status). But the level of education of parent is statistically significantly associated with the response towards the familiarity with mouth guard, where higher proportion (32.4%) of the parents with higher education level were familiar with mouth guard when compared with other level of education (p=0.019). (Table 5)

Table 5. Association between Knowledge of sports mouth guard and characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristics | Are you familiar with sports mouth guard | Χ2- value | p-value | |

| Yes | No | |||

| Parent who responded

Father Mother Age of parent (in years) 20-30 31-40 >40 Level of education Intermediate Secondary Bachelor Higher Education

Socio-economic status Low Middle High

|

13(18.1) 44(17.8)

4(12.1) 25(17.2) 28(19.9)

2(20) 4(7) 39(18.1) 12(32.4)

2(20) 41(15.8) 14(28)

|

59(81.9) 203(82.2)

29(87.9) 120(82.8) 113(80.1)

8(80) 53(93) 176(81.9) 25(67.6)

8(80) 218(84.2) 36(72) |

0.002

1.162

9.963

4.261 |

0.962

0.559

0.019*

0.119 |

*Statistically significant

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the parental knowledge regarding the use of mouth guard during sport activities among school-age children in Riyadh city. The study design offered an assessment of the parents of Saudi children aged (7-12) years old participating in different sport activities in terms of the knowledge, management and experience of the child with dental trauma. Survey sections were structured to offer a profile to clarify the amount of knowledge the parents possess regarding the use of sports-related mouth guards in school-age children to move dental trauma prevention more into mainstream parental dental education programs.

More than half of the parents surveyed had bachelor degree (67.4%) and (81.2%) were of middle level socio-economic status. The latter implies that the practice of physical activities is related to socioeconomic status. Children from lower-income families usually are involved in activities with greater physical contact and violence. However, children with a higher socioeconomic status are more accustomed to using electronic devices (Corrêa Faria et al., 2015, Ayesha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2021).

In addition, level of education of the parent showed to be statistically significantly associated with the response towards the familiarity with mouth guard, where higher proportion (32.4%) of the parents with higher education level were familiar with mouth guard when compared with other level of education (p=0.019). In contrast, Fakhruddin et al. (2007) found that mothers’ educational level was not significant in association to the use of the mouth guards in their children. This could be explained by the different study design and the sample participated in the study. Participating in sport activities increases the risk of dental injuries among school-age children, as shown in this study, the males participating in sports accounted more than half of the sample (56.1%).

This is similar to Tsuchiya et al. (2017) study who reported a significantly higher prevalence (1.5 times) of sports-related dental injuries in male athletes than in female athletes. Sex differences in sports injuries may be caused by a complex mix of intrinsic (e.g., biological differences) and playing environmental factors (e.g., playing management). Out of the 319 participants, 35 (11%) reported that their children had facial or dental injury in which the facial bruising was the most common type among all injuries accounting for (38.3%) followed by the other type of injuries.

In contrast, the study done by Goswami et al. (2017) found that chipping and fracture of teeth was the most reported injury with 28.7% more frequent than any other type. This difference could be explained that the participants in our study were the parents of the children not the children themselves, the type of sports the children were involved in at the time of the injury and the attention of the parents to the face when their child sustains a facial injury over other injuries. Moreover, 18 (38.3%) of parents for children who received trauma to their teeth, reported that the affected teeth were the primary teeth, while 5 (10.6%) reported that the permanent teeth were the affected ones.

On the contrary, Borris et al. (2019) showed that permanent teeth with trauma (64.4%) were more than primary ones (55.6%). This is likely because younger children have immature motor coordination. Almost all the parents who reported their children received different type of injuries also reported they have visited the dentist at different timings post trauma. However, only (26.1%) of parents whom their children received dento-facial trauma visited the dentist immediately. In agreement with our result, Pribble et al. (2004) concluded that small number of parents believed that dento-facial injury is a significant problem.

This might be due to the lack of knowledge about dento-facial injury and their consequences. Furthermore, 17.9% of the participants were familiar and had the knowledge about the use of sports mouth guard which coincides with Goswami et al. (2017) who found that level of awareness and knowledge about sports- related orofacial injury is very poor among children in New Delhi. This shows the significance of the current study which focus on the lack of knowledge regarding the use of sports-related mouth guards and how crucial is their use in the prevention and reduction of dental trauma.

In addition, 5 (1.6%) of the parents stated using mouth guard by their children during sports, which agrees with Turagam (2018) who reported that 90% of the children didn’t use mouth guards during their sport activities. Additionally, the lack of information about the use of mouth guards in the current study was the main reason for not using it which accounts for (81.3%) while other studies reported that discomfort, peer pressure, difficulty breathing, and the children’s coaches did not insist on wearing it were the common barriers for not using mouth guards (Onyeaso, 2004; Pribble et al., 2004).

Three participants reported using the mouth guard used commercially ready-made and the other two were using custom-made at the dental clinic. As a protective measure, custom made mouth guard is more preferable than over the counter appliance (Ranalli et al., 1993; Burt & Overpeck, 2001; Newsome et al., 2001; Tuna & Ozel, 2014).

Nevertheless, knowledge about mouth guards does not necessarily mean their utilization during sports. In fact, the study done by Goswami et al. (2017) on 450 children aged 6 to 16 years stated that the recognition alone is not a significant reason to utilize mouth guards or protective appliances in sport activities and recommended that the cooperation between dentist and sports authorities are important to motivate the players and their trainers about the protective appliances in preventing and reducing orofacial injuries (Tuna & Ozel, 2014, Borris et al., 2019, Ayesha et al., 2020, Li et al., 2021).

As well, it is known that trainers have greater influence effect in the attitude of their players (Ramakrishnan et al., 2019). Trainers can educate the players and their parents about the risk of orofacial injuries associated with contact sports and the cost and morbidity they carry (Al-Habib, 2019). Moreover, as parents have the knowledge about the importance of using protective appliances and mouth guards during sport activities, they might be encouraged to seek the use of mouth guards for their children (Pribble et al., 2004).

Additionally, almost 64% of the participants reported that they will consider using mouth guards for their children during sport activities indicating that parents and guardians are willing to be educated and gain the information of how to prevent and minimize dento-facial trauma that the children may encounter during different sport activities.

This study has limitations to be considered in future studies which included the questionnaire-based survey, in which some elements of underreporting bias might occurred. Also, the small sample of participants who reported that their children experienced dental trauma during sport activities and having an older age group children who are usually more involved in contact sport activities. Finally, the results of the present study demonstrate the insufficient parental knowledge regarding the use of mouth guards for children during sport activities in Riyadh city.

This emphasizes the need to improve the knowledge of the parents and guardians on the importance of the use of mouth guards to prevent and minimize dento-facial trauma to their children when they are involved in different sport activities using a variety of educational methods such as educating the parents or guardians during the children visits to the dental office, distribution of educational flyers in the waiting room, social media posts, and school and sports clubs educational programs.

CONCLUSION

Since dento-facial trauma is common in school-age children while participating in sport activities and using protective appliances such mouth guards can prevent or reduce the effect of trauma, the following measures are recommended: Educational programs to increase the parents, guardians, teachers and coaches awareness by providing them with the information about the usefulness of mouth guards in preventing and reducing the effect of dento-facial trauma. Distribution of educational pamphlets and flyers in dental offices, schools and sports clubs. Educational courses for the dentists and dental students on the important role of protective appliances like the use of mouth-guards to prevent and reduce the effect of dento-facial trauma during sport activities.

REFERENCES

ADA Council on Access Prevention and Interprofessional Relations, ADA Council on Scientific Affairs (2006.) Using mouth-guards to reduce the incidence and severity of sports-related oral injuries. J Am Dent Assoc 137:1712-1720.

Al-Obaida M (2010). Knowledge and Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries in a Group of Saudi Primary School Teachers. Dent Taumatol 26:338-334.

Al-Shamiri H, Alaizari N, Al-Maweri S, Tarakji B (2015). Knowledge and attitude of dental trauma among dental students in Saudi Arabia. Eur J Dent 9:518-522.

AL-Habib A, Alzayer N, Alhabib S, Alalqum S (2019). Parent’s Awareness of Primary Teeth Health: A Case Study in Riyadh and Dammam Dental Clinics. EC Dental Science 18.9:2082-2088.

Andreasen J, Andreasen F, Andersson L (2007). Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth, 4th edn.Oxford:Blackwell Munksgaard.

Aysha, S.A., Rao, H.A., Bhat, S.S., Sundeep, H.K., Shenoy, S., Hegde, N., Suvarna, R. and Sargod, S.S., (2020). Knowledge, Attitude, Perceptions and Practices of Physical Training Instructors of School Athletes Regarding Orofacial Injuries and Mouth Guard Use by the Athletes. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences, 9(49), pp.3748-3753.

Burt C, Overpeck M (2001). Emergency visits for sports-related injuries. Ann Emerg Med 37:301–308.

Collins C, McKenzie L, Roberts K, Fields S, Comstock R (2015). Mouthguard BITES (Behavior, Impulsivity, Theory Evaluation Study): What Drives Mouthguard Use Among High School Basketball and Baseball/Softball Athletes. J Prim Prev 36:323–334.

Corrêa Faria P, Paiva S, Pordeus I, Ramos-Jorge M (2015). Influence of clinical and socioeconomic indicators on dental trauma in preschool children. Braz Oral Res 29:1-7.

Barros D P J, de Araújo T, Soares T, Lenzi M, de Andrade Risso P, Fidalgo T, Maia L (2019). Profiles of Trauma in Primary and Permanent Teeth of Children and Adolescents. J Clin Pediatr Dent 43:5-10.

Fakhruddin K, Lawrence H, Kenny D, Locker D (2007). Use of Mouthguards Among 12- to 14-Year-Old Ontario Schoolchildren. JCDA 73:505-505e.

Green J (2017). The Role of Mouthguards in Preventing and Reducing Sports-related Trauma. Prim Dent J 1:27-34.

Goswami M, Kumar P, Bhushan U (2017). Evaluation of Knowledge, Awareness, and Occurrence of Dental Injuries in Participant Children during Sports in New Delhi: A Pilot Study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 10:373-378.

Holmes C (2000). Mouth protection in sport in Scotland: a review. Br Dent J 188:473–474.

Li, B., Bai, X., Sun, H., Cui, C. and Liu, W., (2021). Knowledge and Implementation of Protective Measures for Oral and Maxillofacial Injuries of Ice Hockey Players in Primary and Secondary Schools in Beijing.

Maestrello-de M, Primroach R (1989). Orofacial trauma and mouth protector wear among high school basketball players. J Dent Child 56:36–39.

Newsome P, Tran D, Cooke M (2001). The role of the mouthguard in the prevention of sports-related dental injuries: a review. Int J Paediatr Dent 11:396-404.

Mekayarajjananonth T, Winkler S, Wongthai P (1999). Improved mouth guard design for protection and comfort. J Pros Dent 82: 627-630.

Nowjack R, Gift H (1996). Use of mouthguards and headgear in organized sports by school-aged children. Public Health Rep 111:82–86.

O’Malley M, Evans D, Hewson A, Owens J (2012). Mouthguard use and dental injury in sport: a questionnaire study of national school children in the west of Ireland. J Ir Dent Assoc 58:205-211.

Onyeaso C (2004). Secondary school athletes: a study of mouthguards. J Natl Med Assoc 96:240–245.

Petersson E, Andersson L, Sorensen S (1997). Traumatic oral vs non-oral injuries. Swed Dent J 21:55–68.

Pribble J, Maio R, Freed G (2004). Parental perceptions regarding mandatory mouthguard use in competitive youth soccer. Inj Prev 10:159-162.

Quaranta A, Giglio O, Coretti C, Vaccaro S, Barbuti G, Strohmenger L (2014). What do parents know about dental trauma among school-age children? A pilot studies. Ann Ig 26:443-446.

Ramakrishnan M, Banu S, Ningthoujam S, Samuel VA (2019). Evaluation of knowledge and attitude of parents about the importance of maintaining primary dentition – A cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care 8:414–418.

Ranalli D, Lancaster D (1993). Attitudes of college football officials regarding NCAA mouthguard regulations and player compliance. J Public Health Dent 53:96-100.

Tsuchiya S, Tsuchiya M, Momma H, Sekiguchi T, Kuroki K, Kanazawa K, et al. (2017). Factors associated with sports-related dental injuries among young athletes: A cross-sectional study in Miyagi prefecture. BMC Oral Health 17:168.

Tuna E, Ozel E (2014). Factors Affecting Sports-Related Orofacial Injuries and the Importance of Mouthguards. Sports Medicine 44:777–783.

Turagam N (2018). Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding oro-facial injuries and mouth guards among parents in Kedah, Malaysia. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 18:27.

Webster D, Bayliss G, Spadaro J (1999). Head and face injuries in scholastic women’s lacrosse with and without eyewear. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31:938–941.

Westerman, B, Stringfellow P, Eccleston J (2002). Beneficial effects of air inclusions on the performance of ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) mouthguard material. Br J Sports Med 36: 51-53.