1Faculty of Psychology Education Universidad de 2 Santiago de Compostela

2Faculty of Psychology, Seville University, Seville, Spain

Corresponding author Email: shadi.k@najah.edu

Article Publishing History

Received: 04/07/2017

Accepted After Revision: 25/09/2017

The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between Basic Psychological Needs including Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness (Deci and Ryan, 2000) and factors predicting resilience (American Psychological, 2010) among Palestinian school students who are living under adversity in the West Bank. The participants were 537 students 13 and 14 years old (45% male and 55% female) representing both urban and rural areas of the northern West Bank. All participants completed the CYRM-28 Psychological Resilience Questionnaire (Liebenberg et al., 2012) and The Basic Psychological Needs Scale-General Version (Ilardi et al., 1993). Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis results showed that the BPN model adequately explained variable variance (MOD FIT/CFI = 0.998) and that satisfying Basic Psychological Needs had positive and significant effect on resilience factors of Caregiving (Physical and Psychological Caregiving), Individual (Personal Skills, Peer Support, and Social Skills), and Context (Spiritual, Education and Cultural Context). The role of (BPN) was significant (® = 0.297, p < 0.001), (® = 0.409, p < 0.001), and (® = 0.241, p < 0.001) respectively Caregiving, Individual, and Context, factors were high (0.711, 0.706, and 0.80) respectively, which in turn indicated that (BPN) plays strong role in explaining the variance of Caregiving, Individual, and Context factors. Based on these findings, (SDT) can predict Resilience factors in case of satisfying (BPN). Findings of the study support that educational and family practices focusing on satisfying psychological needs are related to childhood resilience in the face of adversity.

Resilience, Self-Determination (Sdt), And Basic Psychological Needs (Bpn)

Abualkibash S. K, Lera M. J. Resilience and Basic Psychological Needs Among Palestinian School Students. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2017;10(3).

Abualkibash S. K, Lera M. J. Resilience and Basic Psychological Needs Among Palestinian School Students. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2017;10(3). Available from: https://bit.ly/2ZpUv0M

Introduction

Palestine is a nation in a unique geo-political situation where violence imposed by armed forces and/or military violence as well as with restriction of movement through checkpoints, closures and curfews, and acts of individual and communal threat and humiliation occur regularly. Traumatic events such as shootings, bombings, destruction of houses, physical assaults and deaths occur in some areas on a daily basis Rytter et al., 2006, Abdeen et al., 2008, Soares et al., 2007, Qouta et al., 2008a, Thabet et al., 2016, Thabet, 2015, Mousa Thabet and Vostanis, 2017, Al-Sheikh and Thabet, 2017).

Numerous studies have noted distinct psychological and behavioral impacts of traumatic experiences during situations of political unrest on youth, related to psychological health, well-being, and long term outcomes, including increased risk of suffering from mental health problems, such as; PTSD, insomnia, depression, low feeling of self-efficacy and self-esteem, anxiety and depressive symptoms, cognitive distortions, and behavioral disturbances (Worden, 1996, Saigh et al., 1995, Chimienti et al., 1989, Foa et al., 1999, Baker, 1990, Stubbs and Soroya, 1996, Garbarino and Kostelny, 1993, Moro et al., 1998, Clarke et al., 1993).

It has also been demonstrated that youth in protracted conflict zones exhibit increased difficulties in social relationships, fear of the dark, phobias, bedwetting, social withdrawal, negative social-interaction, aggressive behavior, insecure attachment, forgetfulness, somatic disorders and psychosocial behavioral problems, fear, anger, sadness, humiliation, guilt, nightmares and emotional disregulation (Giaconia et al., 1995, Punamäki, 1997, Foa et al., 1999, Vila et al., 1999, Qouta et al., 2008b), as well as academic challenges such as low grades, concentration difficulties, and truancy from school (Qouta and El-Sarraj, 2004, Kanninen et al., 2003, Thabet and Vostanis, 2000, Altawil, 2008). These indicators reveal how difficult it is for children residing in high conflict zones, such as Palestine, to have a normal developmental trajectory and the high risk for negative lifespan risks related to childhood trauma. Given the high number or young people exposed to traumatic events in Palestine, it is necessary for individual, community, and national well-being and progress to identify protective factors to reduce the potentially negative impacts of this currently inevitable exposure to violence (Hobfoll et al., 2011, Nguyen-Gillham et al., 2008, Thabet and Thabet, 2015a, Thabet and Thabet, 2015b).

Deci and Ryan (2000) Proposes that the relationship between the social contextual environment and people’s well-being is critical for positive human development in Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Self-Determination Theory is based on the tenant that the fulfillment of three Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) including autonomy, competence and relatedness, is essential for positive functioning and when these basic psychological needs are fulfilled, optimal psychological well-being should occur (Gunnell et al., 2013). Ryan and Deci (2000) argue that satisfaction of the (BPN) for autonomy, competence, and relatedness improves well-being, and strengthens inner resources related to resilience, whereas frustration in these three areas increased vulnerability for defense mechanisms and psychopathology (Weinstein and Ryan, 2011, Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013). Weinstein and Ryan (2011), proposed that psychological need satisfaction acts as a buffer in times of stress, reducing both initial appraisals of stress and encouraging adaptive coping after stress-related events occur.

The model of motivational resilience used in this study is based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci and Ryan, 1985), and organized around the assumption that all individuals aim to satisfy the basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy. According to this perspective, humans inherently seek to explore opportunities to satisfy these needs. Individuals feel energized and joyful during interactions in which their needs are satisfied, and frustrated when they are thwarted. Based on their history of experiences in particular situations, people construct views of themselves and the world in relation to these needs. Over time, these expectations come to shape their participation in their environment (Skinner et al., 2014).

The construct of resilience has been broadened from those experiencing severe environmental disruption to include the general population with everyday stressors and difficulties (Timmerman, 2014, Martin and Marsh, 2008). Resilience is intricately related to behavioral autonomy, self-realization, self-regulation, and psychological empowerment (Weston and Parkin, 2010). Resilient individuals exhibit behavioral autonomy in taking responsibility for their actions. Individuals who are resilient are most likely to possess high levels of self-realization and self-efficacy (Timmerman, 2014). Moreover, resilient individuals do not shy away from challenging tasks but exert even more effort, use more effective strategies, and approach difficult tasks with persistence. Resilient individuals self-regulate by planning for and setting goals and consequently monitoring their progress toward these goals. People who exhibit self-realization are aware of their strengths and abilities, reflect upon their past successes with challenging events, develop self-efficacious beliefs in their abilities, and demonstrate greater capacities for responding to future events with resilience (Timmerman, 2014). In addition, research shows a strong association between psychological empowerment and resilience (Pines et al., 2012).

Numerous scholars have noted the bond between resilience and self-determination. Spreitzer (1995) stated that, persons who are empowered or self-determined demonstrate greater resilience. Empowered individuals display resilience, self-determination, power, control, ability, competence, self-efficacy, autonomy, knowledge, and development (Uner and Turan, 2010).

Based on the previous research, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, facilitated by supportive social contexts, appears to foster both a sense of wellness and leads to the building of inner resources that underlie subsequently demonstrated resilience.

The current study was designed to explore the association between factors of resilience factors and the satisfaction of Basic Psychological Needs among Palestinian youth in West-Bank Directorates by using structural equation modeling including:

– The association between (BPN) and Resilience

Material And Methods

Participants And Procedure

The sample consisted of 537 Palestinian public school student’s 13 and 14 years old living in the West Bank (OPT Occupied Palestinian Territories). They were 55% girls and 45% boys. About two thirds (64%) were from rural areas and (36%) from urban areas. For the study, 25 schools were randomly selected as representative of schools in the North directorate of the West Bank. At each school 10 students from 8th grade and 10 students from 9th grade, were randomly selected. The High Ministry of Education provided the permission to access the public schools, and then researcher informed the pupils, their parents, and headmaster about the purpose of study, obtaining their verbal consent for participation.

Measures

The Child and Youth Resilience Measure [CYRM]

(Liebenberg et al., 2012) is a comprehensive instrument composed of three sub-scales, which reflect the major categories of resilience. The first sub-scale is “Individual Factors” that included personal skills (5 items), peer support (2 items) and social skills (4 items). The second sub-scale is labeled “Family Support”, as reflected in physical/material support (2 items) as well as psychological care giving (5 items). The third sub- scale is “Contextual Components” which are environmental characteristics that facilitate a sense of belonging in youth, including spirituality (3 items), culture (5 items), and education (2 items). All responses were measured on a Likert Scale from 1 to 5 (1 = “never” and 5 = “always”), (Liebenberg et al., 2012). The Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated for each dimension in the CYRM-28, (individual factors, family support, and contextual components) 0.80, 0.78 and 0.84 respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale (28 items) was 0.92.

The (BPN) Scale-General Version contains 21 items and is adapted from the (BPN) -work version (Ilardi et al., 1993). Responses for all items were indicated on a Likert Scale from 1 (not true at all) to 7 (definitely true) (Ryan and Deci, 2000). The instrument includes three sub-scale scores, measuring the degree to which the person experiences satisfaction of each of the three needs.

| Table 1: Demographic Characteristics for the Participants | |||

| Demographic variables (n = 537) | Frequencies | (Valid Percentage n = 537) | |

| Gender | Males | 242 | 45 |

| Females | 295 | 55 | |

| Age | 13 | 268 | 50 |

| 14 | 269 | 50 | |

| Place of residence | City | 196 | 34 |

| Village | 341 | 66 | |

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS) (SPSS Version 21) was used to analyze the data. Confirmatory Factor Analysis [CFA] and Path Analysis were used to test psychological resilience related to the factors of individual characteristics, caregiving, contextual components and the Basic Psychological Needs related to autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This study anticipated a positive path from (BPN) to factors of Psychological Resilience (Clauss-Ehlers, 2008, Pines et al., 2012, Ruban et al., 2003, Deci and Ryan, 2000, Skinner et al., 2014, Spreitzer, 1995, Timmerman, 2014, Uner and Turan, 2010, Wehmeyer, 1996, Weston and Parkin, 2010, Tuckman, 2003).

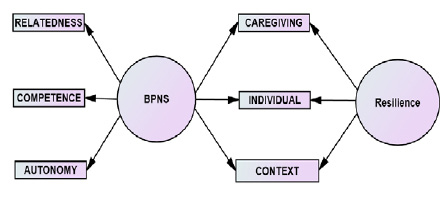

Figure 1, shows the proposed model:

HA: There is positive path from (BPN) to factors indicating Psychological Resilience including individual characteristics, caregiving, and context. (See Figure1).

|

Figure 1: Theoretical model psychological resilience factors and its relationship with satisfaction of BPNS among the Palestinian basic school students in West-Bank |

Results and Discussion

Description of (Bpn) and Resilience

The researchers computed means and SD for (BPN) and its domains (Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness) and for Resilience and its subscales (Individual Characteristics, Caregiving, and Context), (see table 2).

| Table 2: Means and standard deviations of total resilience and resilience factors of children (N = 537) | |||

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| Constructs | Mean | Std. Deviation | N |

| BPNS | 5.1485 | .68308 | 537 |

| Autonomy | 4.9327 | .90893 | 537 |

| Competence | 5.0636 | .83385 | 537 |

| Relatedness | 5.4493 | .80478 | 537 |

| RESILIENCE | 3.7956 | .67234 | 537 |

| Individual Factors | 3.4708 | .62142 | 537 |

| Caregiving Factors | 4.0093 | .81419 | 537 |

| Context Factors | 3.9067 | .79080 | 537 |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Of The Components Of (Bpn) And Resilience

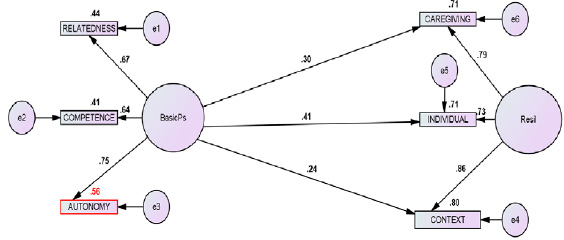

The results indicate that factor loadings were higher than .50, ranging from 0.66 to 0.7 for the (BPN), and higher for the Resilience components from 0.73 to 0.86, At the construct level, the results demonstrate that the reliabilities of all of the constructs ranged from 0.70 to 0.86 (higher than the recommended cut-off of 0.70 for this measure).

The Association Between (Bpn) And Resilience Components

The present study utilizes SEM to test the hypothesized model regarding the relationship between the component variables of (BPN) and Resilience factors including: Individual Characteristics, Caregiving, and Context. The model predicts a positive path from (BPN) to Individual Characteristics, Caregiving, and Context, (the pre-identified components of resilience). Table 4 presents the data on statistical fit for the hypothesized model, using standardized paths coefficients (Beta), and the estimate of variance explained (R2).

The ÷2 value was 8.489 (d.f. = 6, p = 0.204). Therefore, the relative ÷2 was (CMIN/df = 1.415). The RMSEA estimate of 0.028 provided support for the general model. Bentler’s CFI was 0.998 indicating that the proposed model fit the data according to this index.

The goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted GFI (AGFI), and Normed fit index (NFI) for the measure were 0.995, 0.982, and 0.994 respectively; demonstrating general fit. Path coefficients from (BPN) to INDIVIDUAL, CAREGIVING, and CONTEXT as well as total Resilience were significant (see Table 4 and 5).

As shown in table 4 and 5, the standardized path coefficient of caregiving factors from (BPN) was significant (â = 0.297, p < 0.001), R2 (0.711), indicating that (BPN) plays a strong role in explaining the variance of caregiving.

| Table 3: Standardized Path Coefficient and P value | ||

| Parameter Description | Standardized Path Coefficient (â) | P Value |

| Relatedness from BPNS | 0.666** | 0.000 |

| Competence from BPNS | 0.640* | 0.000 |

| Autonomy from BPNS | 0.749** | 0.000 |

| Context from Resilience | 0.861** | 0.000 |

| Individual from Resilience | 0.734** | 0.000 |

| Caregiving from Resilience | 0.789** | 0.000 |

Perditions from Individual Characteristics to (BPN) it was significant (® = 0.409, p < 0.001), R2 for individual factors was high (0.706), which in turn indicated that (BPN) plays strong role in explaining the variance of individual factors; (Individual Personal Skills, Individual Peer Support, and Individual Social Skills).

The variability of Context factors explained by (BPN) it was significant (®= 0.241, p < 0.001). R2 (0.80), which in turn indicated that (BPN) plays strong role in explaining the variance of context factors.

To conclude, figure 2 shows SEM for Resilience factors and their relationship with satisfaction of (BPN).

|

Figure 2: SEM for psychological resilience factors and its relationship with satisfaction of BPNS among the Palestinian basic school students in West-Bank |

As shown in the pervious model and tables 4 and 5, the results revealed that basic psychological needs were significantly and positively associated with the factors of resilience; (individual, caregiving, and context) among the participants.

| Table 4: Model Fit Indices and Recommended Values for SEM Analysis (Kline, 2005) | ||

| Model Fit Index | Model Fit summery | Recommended Values |

| CMIN (Chi-square p value) | 0.204 | > .05 |

| CMIN /df | 1.145 | ≤ 3 |

| CFI | 0.998 | ≥ .90 |

| GFI | 0.995 | ≥ .90 |

| AGFI | 0.982 | ≥ .90 |

| NFI | 0.994 | ≥ .90 |

| RMSEA | 0.028 | ≤ .05 |

| Table 5: Model Fit Indices, Recommended Values for SEM Analysis, and the Observed Values for the Proposed Model | |||||

| Model Fit Index | Observed Values | Parameter Description | Standardized Path Coefficient (â) | P Value | R2 |

| Chi-square value | 8.489 | Relatedness from BPNS | 0.666** | 0.000 | CAREGIVING = 0.711 |

| d.f. | 6 | Competence from BPNS | 0.640* | 0.000 | INDIVIDUAL = 0.706 |

| CMIN (p value) | 0.204 | Autonomy from BPNS | 0.749** | 0.000 | CONTEXT= 0.800 |

| CMIN /df | 1.145 | Context from Resilience | 0.861** | 0.000 | AUTONOMY = 0.561 |

| CFI | 0.998 | Individual from Resilience | 0.734** | 0.000 | COMPETENCE = 0.409 |

| GFI | 0.995 | Caregiving from Resilience | 0.789** | 0.000 | RELATEDNESS = 0.443 |

| AGFI | 0.982 | Caregiving from BPNS | 0.297** | 0.000 | |

| NFI | 0.994 | Individual from BPNS | 0.409** | 0.000 | |

| RMSEA | 0.028 | Context from BPNS | 0.241** | 0.000 | |

Discussion

The study aimed to explore whether the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (BPN) affected resilience factors, in a sample of middle-school students living under situations of geo-political adversity, in Palestine.

Results of the current investigation revealed that the general level of Resilience and (BPN) measures in the sample was high. Additionally, the results revealed that there is significant relationship between (BPN) and the selected factors of Resilience (individual characteristics caregiving, and context), especially between BPN and Individual Characteristics.

The results demonstrate that satisfying basic psychological needs of youth in high conflict environments, has positive effect on resilience and well-being. By reviewing these results it can be supposed that satisfying basic psychological needs positively predicts resilience which is consistent with the explanation offered under self-determination theory (Baard et al., 2004) in which they propose that satisfying basic psychological needs, has a positive effect on resilience and well-being.

Additionally the results of this study are consistent with previous findings that explored (Baard et al., 2004, Deci and Ryan, 2000, Kaydkhorde, 2014), relationships between the children and their families and environmental context as supporting and contributing to satisfaction of basic needs, leading to the facilitation of mental adaptation, resilience and well-being.

Meeting the Basic Psychological Needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness provide essential conditions for positive development and growth, consistency and well-being, (Deci et al., 2001), and may determine a large variance in behavioral functioning (Deci and Ryan, 2017, Sheldon et al., 1996) (Deci and Ryan, 2017).

In conclusion, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is organized around the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (BPN) including autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Students’ histories of experiences with family, school, and the community; including their interactions with parents, teachers, and peers who support or undermine their needs, cumulatively shape their academic identities, or their personal convictions about whether they truly belong (relatedness), have what it takes to succeed (competence), and genuinely endorse the goals and values of schooling (autonomy) Cleary define their resilience, especially in adversive environments. These self-system processes, along with the nature of the academic work students are given (i.e., whether it is authentic, relevant, purposeful, and important) are the proximal predictors of students’ motivational resilience (or vulnerability), including their engagement, coping, and re-engagement (Skinner et al., 2014).

In general, an individual with the skills and characteristics of resilience paired with the traits of self-determined behavior best prepares one to adapt to new environments and increases the utilization of personal responsibility to address pressures they encounter in the environment (Timmerman, 2014). Individuals who capably demonstrate self-determined behaviors and resilience are better able to consistently work toward achieving challenging goals without losing interest or lessening their effort despite hitting a plateau or experiencing outright failure on their first attempt (Timmerman, 2014).

In order to improve resilience among Palestinian children, individual skills factors (personal skills, peer support, and social skills), context factors (spiritually, education and culture) and caregiving factors (physical and psychological) fostering and building suitable educational and academic interventions may be key based on self-determination theory and the current findings. Collective interventions, either at community level or school level may be the best way to effectively address these issues for Palestinean youth and the full range of the population (Rabaia et al., 2010, Pieters, 2016, Hoge et al., 2007).

Limitations

Despite demonstrating (BPN) effects, it is uncertain that the directionality of the effects is in accordance with the model. To further examine these hypotheses and to provide conclusions with respect to the direction of the effect, it is recommended that future research include longitudinal data and school-change interventions.

Further limitations of the current investigation is the self-report nature of the instruments utilized, it was not possible to know exactly how the students interpreted the constructs and whether they viewed the constructs in ways that the researcher intended. While this is a limitation of all survey self-report research of this nature, it should be noted that the confirmatory factor analysis did provide some support that the students were responding as expected. Future research could overcome this limitation by including a mixed methods approach.

References

- abdeen, Z., Qasrawi, R., Nabil, S. & Shaheen, M. 2008. Psychological Reactions To Israeli Occupation: Findings From The National Study Of School-Based Screening In Palestine. International Journal Of Behavioral Development, 32,290-297.

- Al-Sheikh, N. A. M. & Thabet, A. A. M. 2017. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due To War Trauma, Social And Family Support Among Adolescent In The Gaza Strip. J Nurs Health Sci| Volume, 3,

- Altawil, M. A. S. 2008. The Effect Of Chronic Traumatic Experience On Palestinian Children In The Gaza Strip. Phd Doctoral Dissertation, University Of Hertfordshire.

- American Psychological, A. 2010. The Road To Resilience. Retrieved January, 7,

- Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. 2004. Intrinsic Need Satisfaction: A Motivational Basis Of Performance And Well‐Being In Two Work Settings1. Journal Of Applied Social Psychology, 34,2045-2068.

- Baker, A. M. 1990. The Psychological Impact Of The Intifada On Palestinian Children In The Occupied West Bank And Gaza: An Exploratory Study. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry, 60,

- Chimienti, G., Nasr, J. A. & Khalifeh, I. 1989. Children’s Reactions To War-Related Stress. Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology, 24,282-287.

- Clarke, G., Sack, W. H. & Goff, B. 1993. Three Forms Of Stress In Cambodian Adolescent Refugees. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21,65-77.

- Clauss-Ehlers, C. S. 2008. Sociocultural Factors, Resilience, And Coping: Support For A Culturally Sensitive Measure Of Resilience. Journal Of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29,197-212.

- Deci, E. & Ryan, R. 2017. Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs In Motivation, Development, And Wellness. New York, Ny: The Guilford Press.

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation And Self-Determination In Human Behavior, University Of Rochester, Rochester, New York, Usa, Springer Us.

- Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. 2000. The “What” And “Why” Of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs And The Self-Determination Of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11,227-268.

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J. & Kornazheva, B. P. 2001. Need Satisfaction, Motivation, And Well-Being In The Work Organizations Of A Former Eastern Bloc Country: A Cross-Cultural Study Of Self-Determination. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 27,930-942.

- Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F. & Orsillo, S. M. 1999. The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (Ptci): Development And Validation. Psychological Assessment, 11,

- Garbarino, J. & Kostelny, K. 1993. Children’s Response To War: What Do We Know. The Psychological Effects Of War And Violence On Children,23-40.

- Giaconia, R. M., Reinherz, H. Z., Silverman, A. B., Pakiz, B., Frost, A. K. & Cohen, E. 1995. Traumas And Posttraumatic Stress Disorder In A Community Population Of Older Adolescents. Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34,1369-1380.

- Gunnell, K. E., Crocker, P. R. E., Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E. & Zumbo, B. D. 2013. Psychological Need Satisfaction And Thwarting: A Test Of Basic Psychological Needs Theory In Physical Activity Contexts. Psychology Of Sport & Exercise, 14,599-607.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Mancini, A. D., Hall, B. J., Canetti, D. & Bonanno, G. A. 2011. The Limits Of Resilience: Distress Following Chronic Political Violence Among Palestinians. Social Science & Medicine, 72,1400-1408.

- Hoge, E. A., Austin, E. D. & Pollack, M. H. 2007. Resilience: Research Evidence And Conceptual Considerations For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Depression & Anxiety (1091-4269), 24,139-152.

- Ilardi, B. C., Leone, D., Kasser, T. & Ryan, R. M. 1993. Employee And Supervisor Ratings Of Motivation: Main Effects And Discrepancies Associated With Job Satisfaction And Adjustment In A Factory Setting1. Journal Of Applied Social Psychology, 23,1789-1805.

- Kanninen, K., Punamäki, R.-L. & Qouta, S. 2003. Personality And Trauma: Adult Attachment And Posttraumatic Distress Among Former Political Prisoners. Peace And Conflict: Journal Of Peace Psychology, 9,97-126.

- Kaydkhorde, H., Moltafet, G., Chinaveh, M. 2014. Relationship Between Satisfying Psychological Needs And Resilience In High-School Students In Dezful Town. Academic Journal Of Psychological Studies, 3,57-62.

- Kline, R. B. 2005. Principles And Practice Of Structural Equation Modeling. 2005. New York, Ny: Guilford.

- Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M. & Van De Vijver, F. 2012. Validation Of The Child And Youth Resilience Measure-28 (Cyrm-28) Among Canadian Youth. Research On Social Work Practice, 22,219-226.

- Martin, A. J. & Marsh, H. W. 2008. Academic Buoyancy: Towards An Understanding Of Students’ Everyday Academic Resilience. Journal Of School Psychology, 46,53-83.

- Moro, L., Franc iškovic , T., Varenina, G. & Urlic , I. War Trauma: Influence On Individuals And Community. War Violence, Trauma And Coping Process, 1998.

- Mousa Thabet, A. A. & Vostanis, P. 2017. Relationships Between Traumatic Events, Religious Coping Style, And Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Palestinians In The Gaza Strip. J Nurs Health Stud, 2,

- Nguyen-Gillham, V., Giacaman, R., Naser, G. & Boyce, W. 2008. Normalising The Abnormal: Palestinian Youth And The Contradictions Of Resilience In Protracted Conflict. Health Soc Care Community, 16,291-8.

- Pieters, H. C. 2016. “I’m Still Here”: Resilience Among Older Survivors Of Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs, 39,E20-8.

- Pines, E. W., Rauschhuber, M. L., Norgan, G. H., Cook, J. D., Canchola, L., Richardson, C. & Jones, M. E. 2012. Stress Resiliency, Psychological Empowerment And Conflict Management Styles Among Baccalaureate Nursing Students. Journal Of Advanced Nursing, 68,1482-1493.

- Punamäki, R.-L. 1997. Determinants And Mental Health Effects Of Dream Recall Among Children Living In Traumatic Conditions. Dreaming, 7,

- Qouta, S. & El-Sarraj, E. 2004. Prevalence Of Ptsd Among Palestinian Children In Gaza Strip. Arabpsynet Journal, 2,8-13.

- Qouta, S., Punamäki, R.-L. & El Sarraj, E. 2008a. Child Development And Family Mental Health In War And Military Violence: The Palestinian Experience. International Journal Of Behavioral Development, 32,310-321.

- Qouta, S., Punamäki, R. L., Miller, T. & El‐Sarraj, E. 2008b. Does War Beget Child Aggression? Military Violence, Gender, Age And Aggressive Behavior In Two Palestinian Samples. Aggressive Behavior, 34,231-244.

- Rabaia, Y., Giacaman, R. & Nguyen-Gillham, V. 2010. Violence And Adolescent Mental Health In The Occupied Palestinian Territory: A Contextual Approach. Asia-Pacific Journal Of Public Health / Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium For Public Health, 22,216s-221s.

- Ruban, L. M., Mccoach, D. B., Mcguire, J. M. & Reis, S. M. 2003. The Differential Impact Of Academic Self-Regulatory Methods On Academic Achievement Among University Students With And Without Learning Disabilities. Journal Of Learning Disabilities, 36,270-286.

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. 2000. Self-Determination Theory And The Facilitation Of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, And Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55,68-78.

- Rytter, M. J. H., Kjældgaard, A.-L., Brønnum-Hansen, H. & Helweg-Larsen, K. 2006. Effects Of Armed Conflict On Access To Emergency Health Care In Palestinian West Bank: Systematic Collection Of Data In Emergency Departments. Bmj, 332,1122-1124.

- Saigh, P. A., Mroueh, M., Zimmerman, B. J. & Fairbank, J. A. 1995. Self-Efficacy Expectations Among Traumatized Adolescents. Behaviour Research And Therapy, 33,701-704.

- Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M. & Reis, H. T. 1996. What Makes For A Good Day? Competence And Autonomy In The Day And In The Person. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin,1270-1279.

- Skinner, E., Pitzer, J. & Brule, H. 2014. The Role Of Emotion In Engagement, Coping, And The Development Of Motivational Resilience. International Handbook Of Emotions In Education,331-347.

- Soares, A. M., Farhangmehr, M. & Shoham, A. 2007. Hofstede’s Dimensions Of Culture In International Marketing Studies. Journal Of Business Research, 60,277-284.

- Spreitzer, G. M. 1995. Psychological Empowerment In The Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, And Validation. Academy Of Management Journal, 38,1442-1465.

- Stubbs, P. & Soroya, B. 1996. War Trauma, Psycho‐Social Projects And Social Development In Croatia. Medicine, Conflict And Survival, 12,303-314.

- Thabet, A. A. & Vostanis, P. 2000. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Reactions In Children Of War: A Longitudinal Study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24,291-298.

- Thabet, A. M. & Thabet, S. S. 2015a. Trauma, Ptsd, Anxiety, And Resilience In Palestinian Children In The Gaza Strip. British Journal Of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 11,1-13.

- Thabet, A. M. & Thabet, S. S. 2015b. Trauma, Ptsd, Anxiety, And Resilience In Palestinian Children In The Gaza Strip.

- Thabet, A. M., Thabet, S. S. & Vostanis, P. 2016. The Relationship Between War Trauma, Ptsd, Depression, And Anxiety Among Palestinian Children In The Gaza Strip. Health Science Journal.

- Thabet, S. S. 2015. Stress, Trauma, Psychological Problems, Quality Of Life, And Resilience Of Palestinian Families In The Gaza Strip. Clinical Psychiatry.

- Timmerman, L. C. 2014. Self-Determination In Transitioning First-Year College Students With And Without Disabilities: Using Map-Works For Assessment. Ball State University.

- TUCKMAN, B. W. 2003. The Effect of Learning and Motivation Strategies Training on College Studentsi Achievement. Journal of College Student Development, 44,430-437.

- UNER, S. & TURAN, S. 2010. The construct validity and reliability of the Turkish version of Spreitzer’s psychological empowerment scale. BMC public health, 10,

- VANSTEENKISTE, M. & RYAN, R. M. 2013. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23,263-280.

- VILA, G., PORCHE, L.-M. & MOUREN-SIMEONI, M.-C. 1999. An 18-month longitudinal study of posttraumatic disorders in children who were taken hostage in their school. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61,746-754.

- WEHMEYER, M. L. 1996. Self-determination as an educational outcome: Why is it important to children, youth and adults with disabilities. Self-determination across the life span: Independence and choice for people with disabilities,

15-34. - WEINSTEIN, N. & RYAN, R. M. 2011. A self-determination theory approach to understanding stress incursion and responses. Stress & Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 27,4-17.

- WESTON, K. J. & PARKIN, J. R. 2010. Resilience. Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology. Springer.

- WORDEN, J. W. 1996. Children and grief: When a parent dies, Guilford Press.