Medical

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 9(4): 878-883 (2016)

Application of WHOQOL-BREF for the evaluation of

the quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure

Mahshid Borumandpour* Medical Student, Medical School, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran,

Gholamabbas Valizadeh Cardiologist, Medical School, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran,

Azizallah Dehghan Ph.D Epidemiology, Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Fasa University

of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran, Alireza Pourmarjani, Research Center for Health Sciences, Department

Epidemiology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran and Maryam Ahmadifar Medical Student,

Medical School, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran

ABSTRACT

Heart failure is the most common cardiovascular disease and its prevalence and incidence increase as the age goes up.

This chronic situation affects the quality of life of patients and their family. The main objective of this study was to

determine quality of life of elderly patients with heart failure. A cross-sectional study conducted among 150 patients

with heart failure aged 50 and above who entered cardiovascular clinic and Coronary Care Unit (CCU) ward of Vali-

Asr hospital of Fasa, Iran, from March to August 2013. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50%

entered. WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was used to evaluate the quality of life of patients. All the statistical analyses

were performed using the statistical package for social sciences version 16.0. Overall we enrolled 147 patients includ-

ing 77 (52.3 %) males and 70 (47.7 %) females with the mean age ± standard deviation of 63±27 years. There was

not any signi cant relationship between NYHA class, ejection fraction, past medical history of hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, pulmonary hypertension in patients and variables of

our questionnaire. Social and environmental aspects were the highest and lowest scores of this questionnaire, respec-

tively (53.85 ±21.28 and 45.74 ±17.67). There was not any correlation between job of patients and any aspect of

their quality of life (p-value = 0.49 for total).Our results indicated that the majority of heart failure patients had poor

and undesirable quality of life and the women have weaker scores of quality of life variations than men. Therefore,

controlling some available variables among these patients is suggested.

KEY WORDS: HEART FAILURE, QUALITY OF LIFE, WHOQOL-BREF

878

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: mahshid.boroomand@yahoo.com

Received 19

th

Sept, 2016

Accepted after revision 21

st

Dec, 2016

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2015: 3.48 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2016. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

Mahshid Borumandpour

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure is the most common cardiovascular dis-

ease as a chronic, progressive, and disabling disease,

worldwide. Its prevalence and incidence increase as the

age goes up; that approximately one percent of more

than 50 years old people and 10 percent of people older

than 80 years old suffer from heart failure in the United

States. In addition, with the progression in medical care

and surgery, patients who survive myocardial infarction

subsequently develop with heart failure (Jaarsma et al.,

2000).Increase in the prevalence of heart failure results

from complications of infections, in ammation, vascu-

lar, and valvular heart disease. Therefore, it has become

a major health problem and an epidemic disorder in the

United States. Five million people suffer from heart fail-

ure in this state which approximately 500,000 new cases

add to this number annually and are expected to be dou-

bled in the next 30 years (Zambroski, Moser, Bhat, &

Ziegler, 2005).According to the Center of Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) a study published in the year 1380

and showed that the number of patients with heart fail-

ure that have been reported in 18 provinces was 3337

per 100,000 populations. In an epidemiological survey

in the year 1377 in Iran, 25% of patients hospitalized

in different wards of hospital were cases of heart failure

(Rahnavard et al 2006).

Heart failure symptoms are something shortness of

breath and blood ow, dizziness, angina, edema, and

ascites. These symptoms predispose the patients to expe-

rience exercise intolerance and changes in their lifestyle

that nally affect their life satisfaction and quality.

Patients will be restricted in job tasks, family interac-

tions, and social life that will nally lead to social isola-

tion and depression (Dunderdale et al 2005).Based on

who organization, the quality of life is people’s de ni-

tion of their selves in life from many aspects such as cul-

ture, their goals in their life, value of their living system,

expectations, their standard beliefs and their priorities.

Therefore, it has been a subjective issue which is not

visible for anyone. Moreover, it is based on people’s per-

ceptions of the different aspects of their lives (Dehghan

et al 2011). In health care system, control and giving

good care to chronic diseases is very important these

days, these diseases healing is almost impossible but

their fatality is not imminent. So, improving the quality

of life should be considered as a consequent of clinical

and medical researcher (Kash et al 2015).

Martensson et al.(2003) have also suggested that the

primary source of depression and decrease in the quality

of life in these patients is due to the adverse physical

symptoms of the disease.Exercise intolerance disable the

patients to perform activities of daily living, it creates

dependency and help resulting in decrease in their qual-

ity of life (Molloy et al 2005). Mc Murray et al. carried

out a study on heart failure patients in the year 2004

and concluded that the total years of potential life lost

in heart failure patients is 6.7 years per 1,000 men and

5.1 years per 1000 women in Australia (McMurray &

Stewart, 2002).

Shojaie (2008) studied the quality of life of 250

patients with heart failure in Tehran, which revealed that

76.4% of patients had undesirable and relatively desira-

ble quality of life. According to this study, increase in the

age and the frequency of hospitalization and prolonged

disease will make much poorer quality of life for these

patients.Another similar study was done in Zahedan Iran

by Ebrahimi et al. (2007) They concluded that there is a

relationship between the quality of life and job, marital

status, age, disease duration and the frequency of hos-

pitalization. In addition, there is a signi cant relation-

ship between being male and experiencing a better life

quality. This study showed the negative impact of heart

disease on the quality of life .According to aging popu-

lation in Iran and increase in cardiovascular diseases in

developing countries, we conducted this study to assay

the quality of life of elderly patients with heart failure.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this prospective cross-sectional study, 150 patients

with heart failure entered cardiovascular clinic and

Coronary Care Unit (CCU) ward of Vali-Asr hospital, a

tertiary health care center af liated with Fasa University

of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran, from March to August

2013. Patients were included according to the American

Heart Association criteria of diagnosing cardiovascular

disease (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009). Patients with stable

congestive heart failure, (NYHA class I–III) who referred

to the hospital and clinics of cardiovascular disease

enrolled the study. Inclusion criterion was a left ven-

tricular ejection fraction below 50%, as determined by

transthoracic echocardiography. Patients in NYHA func-

tional class IV were excluded, as were those who had

neurological, orthopedic, peripheral vascular, or severe

pulmonary diseases. Furthermore, patients were divided

into four groups according to the stage of heart failure

as follows: stage one: risk factor only, stage two: symp-

toms without signs, stage three: existences of signs but

improved by drugs, and stage four: existences of signs

without any improvement with drugs.

Demographic information was recorded by a

researcher checklist. The quality of life of the patients

were assessed with World Health Organization (WHO)

quality of life questionnaire. This questionnaire included

demographic information and ve dimensions of heart

failure patients` quality of life. Trained people helped

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS APPLICATION OF WHOQOL-BREF FOR THE EVALUATION OF HEART FAILURE 879

Mahshid Borumandpour

the illiterate patients to ll out the questionnaire.

(WHOQOL-BREF), this instrument is one of the known

instruments that has been developed for cross-cultural

comparisons of QOL and is available in many languages

(Gholami et al 2013).

Whoqol-BREF questionnaire evaluates QOL in four

aspects, physical, psychological, social and environmen-

tal health, with 24 questions (7-6-3 and 8 questions for

each dimension). The rst two questions are not related

to any aspect and evaluate the patient’s health and the

quality of life generally. Therefore, this questionnaire

has 26 questions overall. Scores for each aspect would

be between four and 20 that score four shows the worst

and 20 shows the best condition. These scores are con-

vertible to another score with the domain of 0-100 (Deh-

ghan et al., 2016).Persian version of this questionnaire

was prepared by Nedjat et al. and it has good validity

and reliability for evaluating QOL in the Persian speak-

ers (Nedjat et al 2008).To ll out the questionnaire for

illiterate patients trained people was used. The

study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of Fasa University of

Medical Sciences and all the participants signed a writ-

ten informed consent (Approval number: 26492/A/28).

The protocol of the study was approved by the Institu-

tional Review Board of the University.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All the statistical analyses were performed using the sta-

tistical package for social sciences version 16.0 (SPSS

16). Descriptive results were expressed as mean value

± standard deviation. Qualitative data were expressed

by frequency and relative frequency. One way ANOVA

and Mann Whitney test were used for comparing the

scores of quality of life dimensions between the differ-

ent groups.

RESULTS

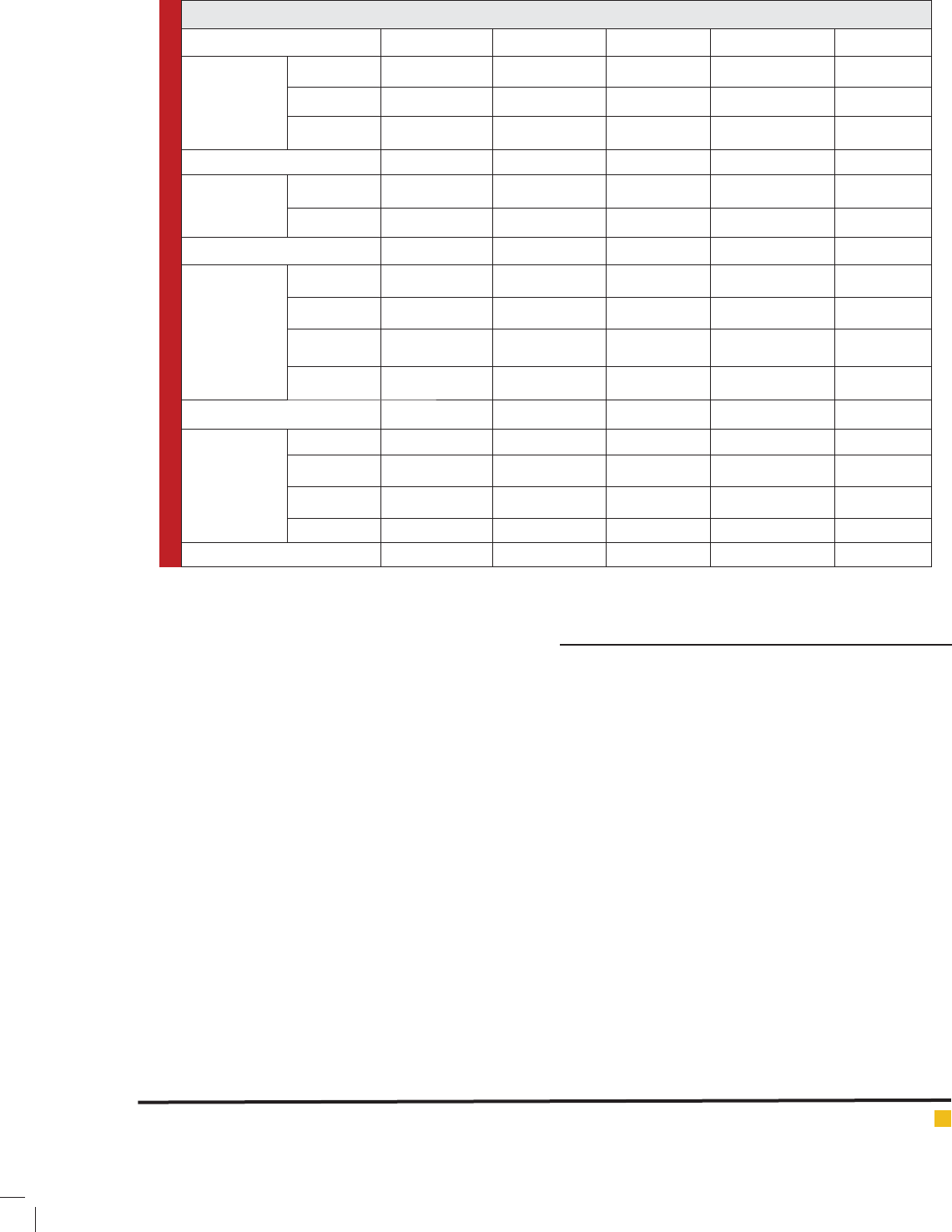

Overall, we enrolled 147 patients (3 of 150 excluded

during the study) including 77 (52.3 %) males and 70

(47.7 %) females referring to internal clinic and CCU

ward of Vali-Asr hospital (Fasa, Iran). The mean age of

patients was 63± 27 years. Demographic data is availa-

ble in Table.1.Also the quality of life dimensions of heart

failure patients has been shown in Table 2. Physical,

psychological, social, and environmental are all aspects

of WHO quality of life questionnaire that is scored in

this table.

Past medical history of hypertension, diabetes mel-

litus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal

failure, and pulmonary hypertension of patients

were extracted and each questionnaire variables were

assessed with them, but there was not any signi cant

relationship. (P-value = 0.40, 0.14, 0.50, 0.77, and 0.91,

respectively).

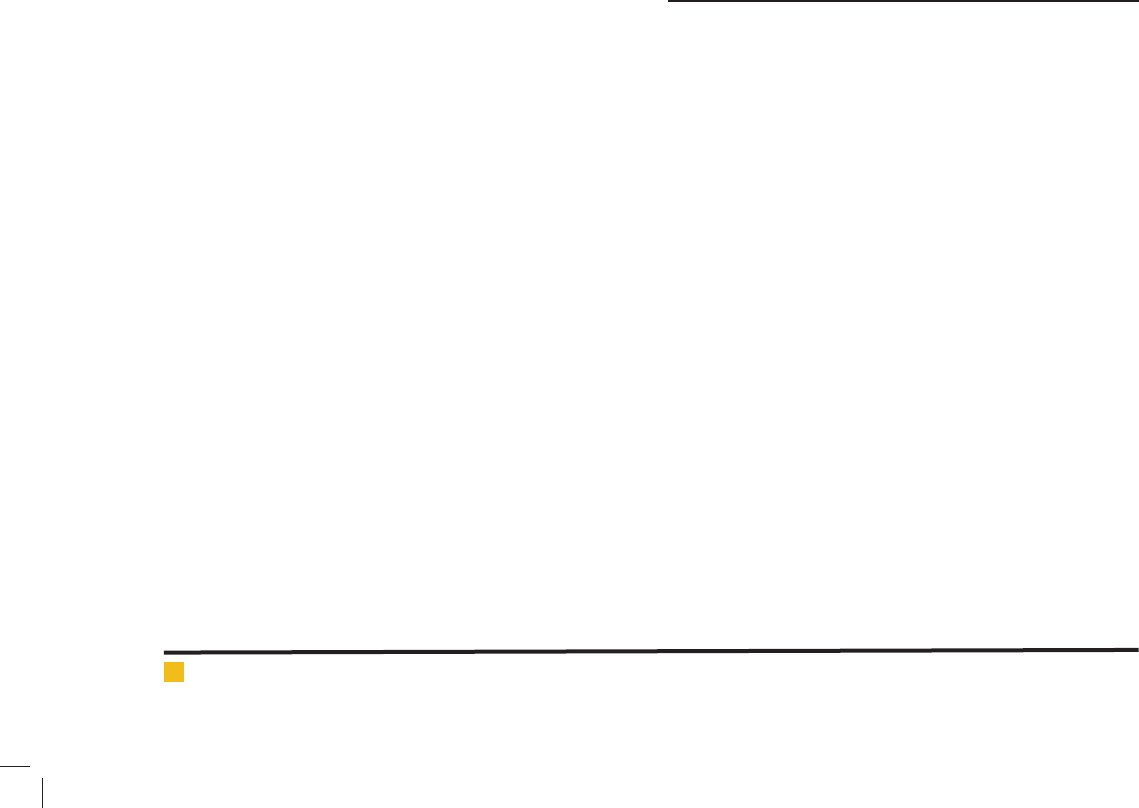

The scores of the questionnaire dimensions and their

correlation with age, sex, education, and stage of heart

failure is summarized in Table 3.3. Ejection fraction of

the patients didn`t have any relationship with these vari-

ations (p-value = 0.61).There was not any correlation

Table 1: Demographic data of heart failure patients

Variable Under 60

Frequency (%)

Between 60 and 70

Frequency (%)

More than 70

Frequency (%)

Age 45 (30.6) 37 (25.1) 65 (44.3)

Male

Frequency (%)

Female

Frequency (%)

Sex 77 (52.3) 70 (47.7)

Illiterate

Frequency (%)

Elementary 1

Frequency (%)

Elementary 2

Frequency (%)

Collegiate

Frequency (%)

Education 84 (57.1) 34 (23.1) 23 (15.6) 6 (4.2)

Table 2: Quality of life dimensions of patients with heart failure

Variable Minimum Maximum Mean ± Standard deviation

Physical 3.57 96.43 48.42±20.09

Psychological 12.50 83.33 49.97±14.99

Social 0.00 100.00 53.85 ±21.28

Environmental 6.25 90.63 45.74 ±17.67

880 FISH DIVERSITY OF WULAR LAKE KASHMIR INDIA BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Mahshid Borumandpour

Table 3: Scores of questionnaire variations and their correlation with age, sex, education, and stage of heart failure

Variable Physical Psychological Social Environmental Total

Age < 60 49.76±18.51 48.98±15.96 54.62±20.37 46.73±15.91 51.38±27.72

60-70 50.09±19.73 49.77±14.59 54.95±16.71 43.15±16.48 37.16±26.59

> 70 46.53±21.44 50.76±14.71 52.69±24.25 46.53±19.50 46.53±27.99

P value 0.70 0.78 0.83 0.56 0.06

Sex Male 47.72±20.71 49.89±15.33 53.57±21.22 45.21±18.50 48.21±27.92

Female 49.18±19.50 50.05±14.71 54.16±21.50 46.33±16.83 42.85±27.79

P value 0.59 0.90 0.84 0.83 0.25

Education Illiterate 48.25±19.88 49.50±14.78 52.97±22.09 45.34±16.98 45.53±28.56

Elementary 1 45.90±22.41 50.61±14.61 54.41±22.95 44.76±20.10 44.85±24.25

Elementary 2 52.63±19.89 50.00±17.45 56.52±17.39 49.59±15.20 46.19±28.56

Collegiate 48.80±6.64 52.77±13.08 52.77±16.38 42.18±23.61 50.00±41.07

P value 0.69 0.89 0.86 0.67 0.98

Stage of heart

failure

Stage 1 30.35±19.45 50.00±10.20 37.50±27.63 37.50±22.24 50.00±20.41

Stage 2 49.72±17.58 49.35±14.27 53.52±21.10 47.71±18.44 45.19±28.95

Stage 3 47.46±19.39 50.29±15.53 53.75±20.11 45.40±16.83 47.25±28.01

Stage 4 56.30±25.45 49.01±14.77 58.82±26.42 46.69±21.17 36.02±27.20

P value 0.18 0.96 0.52 0.77 0.50

between NYHA class of patients and their quality of life

aspects, neither (p-value = 0.34)

Moreover, there was not any correlation between the

job of patients and any aspect of their quality of life

(p-value = 0.49 for total). Number of hospital admis-

sion days of patients and variations of questionnaire

were also compared with each other. None of them had

correlation with hospital staying days of the patients.

(P-value = 0.06 for physical, p-value = 0.17 for psy-

chological, p-value = 0.07 for social, p-value = 0.87

for environmental, and P-value = 0.69 for total). It is

obvious that if our sample size was much more, scores

of physical and social aspect of heart failure quality of

life might be signi cantly correlated with hospital stay-

ing days of the patients. Patients who underwent selec-

tive coronary angiography and coronary artery bypass

graft operation did not have any signi cant correlation

with any dimensions of quality of life questionnaire

(p-value= 0.49 and 0.85, respectively). In patients who

underwent percutaneous intervention environmental

aspect and total score of questionnaire were correlated

with this intervention. (P-value= 0.014 for environmen-

tal and p-value= 0.023 for total)

DISCUSSION

Access to the information about the quality of life,

moreover to treatment, promote supportive programs

and rehabilitation proceedings in many societies. Today,

people are demanding improved quality of life that

is why the governments are increasingly focusing on

improving the quality of life of their people and are try-

ing to reduce disease; they also secure health services,

physical, mental, and social welfare for their popula-

tion (Park, Sands, & Marek, 1995).We found in our study

that the score of all the aspects of patients’ quality of

life are in relatively desirable spectrum. Maximum score

belonged to social dimension of the heart failure quality

of life questionnaire. According to many researchers, the

majority of heart failure patients have an undesirable

life quality (Jaarsma et al., 2000) (Juenger et al., 2002)

(Wielenga et al., 1998). Also it has been declared that

congestive heart failure occurs more than other chronic

diseases, which disturb patients` quality of life (Cline

et al 1999).

In our study, we reached to this theory that the qual-

ity of life of younger patients is much better than elderly

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS APPLICATION OF WHOQOL-BREF FOR THE EVALUATION OF HEART FAILURE 881

Mahshid Borumandpour

patients. In other words, patients under 60 years old had

better life quality. Shojaie (2008) also stated that patients

between 40 to 60 years old have much desirable quality

of life than other age spectrums especially elderly peo-

ple. Moreover Stewart et al. 2008) stated that males have

a better quality of life but we didn`t see any signi cant

difference between males and females quality of life in

our study. In another study the comparison of the qual-

ity of life dimensions in women and men showed that

physical function (P=0.005) and mental health (P=0.01)

were signi cantly higher in men than women (Abedi

et al 2011).

Perhaps the main cause of these ndings is as follows:

Men are very active people in the period before being

retired; but they af icted to heart failure in the years

after this section of life. While majority of women in

this survey are homemakers and notwithstanding suffer-

ing from chronic diseases. This task dramatically reduces

their quality of life. Riedinger et al (2006) performed a

cross-sectional study and found that women do much

less exercise than men that this leads to a decrease in

functional capacity and deterioration of their physical

condition and nally affects their quality of life (Ried-

inger et al 2002).

In the present study, the quality of life of the patients

older than 70 years old are so low and this quality

became worsen with the increasing age. Johansson et

al. ( 2006) and Shojaie ( (2008) concluded similar conse-

quences but Rahnavard et al., (2006) did not found any

signi cant correlation between the age and the qual-

ity of life of heart failure patients. Level of education

by establishing fundamental change in knowledge and

attitude has always been effective in health, disease, and

all aspects of human life. It is also considered as a factor

affecting the quality of life of patients in many previous

studies. We found in the present study that heart failure

patients with college education have much more desir-

able quality of life than other groups. In other words, the

higher the educational level, the more favorable quality

of life the patient will have. This theory has been proven

in some other studies (Rahnavard et al., 2006) (Esmaeili,

2004; Shojaei, 2008).Percentage of ejection fraction is

the ratio of end-diastolic volume of blood in each con-

traction that exited from heart chambers and is affected

in heart failure. We did not nd any correlation between

the amount of ejection fraction and the quality of life

of patients but Juenger et al (2002) expressed that with

increase in the severity of heart disease and decrease

in ejection fraction, the quality of life will be signi -

cantly decreased. They also expressed that the percent-

age of ejection fraction is a measure of heart function

and its reduction demonstrates the disease severity.

Another variation that affects the quality of life of these

patients is the stage of heart failure. The stage of heart

failure shows the severity of the disease and represents

the responsibility of patients to our treatment package.

In our study, patients were divided into four groups

according to the stage of their disease. The scores of the

quality of life questionnaire in stage four of heart failure

were less than other groups.

Interventions are some actions that in uence on all

aspects of life especially its quality. Percutaneous inter-

vention is an invasive intervention that may affect the

quality of life of heart failure patients. Our results also

revealed that patients who underwent this intervention

in course of their disease had lower scores of the ques-

tionnaire dimensions than patients without any inter-

vention. We think that some of our results and com-

parisons were unstable due to small sample size of the

study. We suggest to choose a bigger sample in future

studies in order to evaluate heart failure patients` qual-

ity of life more exactly. The burden of the disease on

patients, their family, and society are some related vari-

ations that could be assessed in next studies. Our results

indicated that the majority of heart failure patients had

poor and undesirable quality of life and the women have

weaker scores of quality of life variations than men.

Therefore, controlling some available variables among

these patients is suggested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This article is the result of medical student theses In Fasa

University of Medical Sciences, Iran. We appreciate the

deputy of research and technology of Fasa University of

medical sciences for supported this research.

REFERENCES

Abedi, H. A., Yasaman A. M. and Abdeyazdan G. H. (2011).

Quality of life in heart failure patients referred to the Kerman

outpatient centers, 2010.

Cline, C. M., Willenheimer, R. B., Erhardt, L. R., Wiklund, I., &

Israelsson, B. Y. (1999). Health-related quality of life in elderly

patients with heart failure. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Jour-

nal, 33(5), 278-285.

Dehghan, A., Ghaem, H., Borhani-Haghighi, A., Safari-Far-

amani, R., Moosazadeh, M., & Gholami, A. (2016). Evaluation

of reliability and validity of PDQ-39: questionnaire in iranian

patients with parkinson’s disease. Zahedan Journal of Research

in Medical Sciences, 18(3).

Dehghan, A., Ghaem, H., Borhani Haghighi, A., Kash , S., &

Zeyghami, B. (2011). Comparison of quality of life in Parkin-

son’s patients with and without fatigue. Bimonthly Journal of

Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, 15(1), 49-55.

Dunderdale, K., Thompson, D. R., Miles, J. N., Beer, S. F., &

Furze, G. (2005). Quality‐of‐life measurement in chronic heart

882 FISH DIVERSITY OF WULAR LAKE KASHMIR INDIA BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Mahshid Borumandpour

failure: do we take account of the patient perspective? Euro-

pean journal of heart failure, 7(4), 572-582.

Ebrahimi Tabas , E., Khamrani, M., Rezvani Amin, M., & Pour-

namdar, Z. (2007). Quality of life and related factors in patients

with heart failure in CCU wards of Khatam the (PBUH) and Ali

Ibn Abi Talib (AS) hospitals in Zahedan. 21-22.

Esmaeili, M. (2004). Self-care self-ef ciency and quality of life

among patients receiving homedialysis.

Gholami, A., Jahromi, L. M., Zarei, E., & Dehghan, A. (2013).

Application of WHOQOL-BREF in measuring quality of life in

health-care staff. International journal of preventive medicine,

4(7).

Jaarsma, T., Halfens, R., Tan, F., Abu-Saad, H. H., Dracup, K.,

& Diederiks, J. (2000). Self-care and quality of life in patients

with advanced heart failure: the effect of a supportive educa-

tional intervention. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and

Critical Care, 29(5), 319-330.

Johansson, P., Dahlström, U., & Broström, A. (2006). Factors

and interventions in uencing health-related quality of life in

patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. European

Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 5(1), 5-15.

Juenger, J., Schellberg, D., Kraemer, S., Haunstetter, A., Zugck,

C., Herzog, W., & Haass, M. (2002). Health related quality of

life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with

other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables.

Heart, 87(3), 235-241.

Kash , S. M., Nasri, A., Dehghan, A., & Yazdankhah, M. (2015).

Comparison of quality of life of patients with type II diabetes

referring to diabetes association of Larestan with Healthy peo-

ple in 2013. J Neyshabur Univ Med Sci, 3(2), 32-38.

Lloyd-Jones, D., Adams, R., Carnethon, M., De Simone, G., Fer-

guson, T. B., Flegal, K., . . . Greenlund, K. (2009). Heart disease

and stroke statistics—2009 update a report from the American

Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics

Subcommittee. Circulation, 119(3), e21-e181.

Mårtensson, J., Dracup, K., Canary, C., & Fridlund, B. (2003).

Living with heart failure: depression and quality of life in

patients and spouses. The Journal of heart and lung transplan-

tation, 22(4), 460-467.

McMurray, J., & Stewart, S. (2002). The burden of heart failure.

European Heart Journal Supplements, 4(suppl D), D50-D58.

Molloy, G. J., Johnston, D. W., & Witham, M. D. (2005). Family

caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis.

European journal of heart failure, 7(4), 592-603.

Nedjat, S., Montazeri, A., Holakouie, K., Mohammad, K., &

Majdzadeh, R. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Iranian

interview-administered version of the World Health Organiza-

tion’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): a popu-

lation-based study. BMC health services research, 8(1), 1.

Park, W., Sands, J., & Marek, J. (1995). Medical surgical nurs-

ing: Concepts and clinical practice. St. Louis: Mosby, 17.

Rahnavard, Z., Zolfaghari, M., Kazemnejad, A., & Hatamipour,

K. (2006). An investigation of quality of life and factors affect-

ing it in the patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of

hayat, 12(1), 77-86.

Rahnavard , Z., Zolfaghari, M., Kazermnejad, A., & Hatamipour,

K. (2006). An investigation of aulity of life and factors affect-

ing it in the patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of

Hayat, 77-86.

Riedinger, M. S., Dracup, K. A., Brecht, M.-L., & Investigators,

S. (2002). Quality of life in women with heart failure, norma-

tive groups, and patients with other chronic conditions. Amer-

ican Journal of Critical Care, 11(3), 211-219.

Shojaei, F. (2008). Quality of life in patients with heart failure.

Journal of hayat, 14(2), 5-13.

Stewart, S., & Blue, L. (2008). Improving outcomes in chronic

heart failure: a practical guide to specialist nurse intervention:

John Wiley & Sons.

Wielenga, R. P., Erdman, R. A., Huisveld, I. A., Bol, E., Dun-

selman, P. H., Baselier, M. R., & Mosterd, W. L. (1998). Effect

of exercise training on quality of life in patients with chronic

heart failure. Journal of psychosomatic research, 45(5), 459-

464.

Zambroski, C. H., Moser, D. K., Bhat, G., & Ziegler, C. (2005).

Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on qual-

ity of life in patients with heart failure. European Journal of

Cardiovascular Nursing, 4(3), 198-206.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS APPLICATION OF WHOQOL-BREF FOR THE EVALUATION OF HEART FAILURE 883