1College of Medicine, University of Hail, Hail, KSA

2College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Hail, Hail, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Corresponding author Email: jahooralam@gmail.com

Article Publishing History

Received: 12/01/2019

Accepted After Revision: 12/03/2019

The present study was aimed to assess the level of awareness of knowledge, awareness and practices of physicians in Primary-Care Centers Hail, Saudi Arabia. Cross-sectional and descriptive responses were obtained by using a semistructured multi-point questionnaire that was prepared in English as well as in Arabic. It consisted of open and closedended questions. The data were analyzed using SPSS tool. A total of 62 subjects were included in the study. More than one third of subjects were <40 years of age with mean age of 44.26±11.00 ranging from 26-72 years. Majority

viewed that diabetic type 1 patient should visit an ophthalmologist after diagnosis (82.3%). Retinal vascular disease was reported as the most common eye disease associated with diabetic retinopathy (66.1%). About one third of the subjects adapted direct (hand-held) ophthalmoscope and a dilated fundus exam for evaluating diabetic retinopathy each constituting 33.9% and 32.3% respectively. Journals were the main source of knowledge about diabetic retinopathy (72.6%). This study displays the need for hands on training of physicians about detection of diabetic retinopathy by direct use of ophthalmoscopes. Barriers for ophthalmoscope examination as perceived need to be further addressed and evaluated.

Diabetic Retinopathy, Knowledge, Awareness, Practices, Physicians.

Alshammari A. E, M, Alshammari E. M. A, Alshammari A. M. F, Saleem M, Alam M. J. A study on awareness and practices of physicians about diabetic retinopathy in primary-care centers Hail, Saudi Arabia. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2019;12(1).

Alshammari A. E, M, Alshammari E. M. A, Alshammari A. M. F, Saleem M, Alam M. J. A study on awareness and practices of physicians about diabetic retinopathy in primary-care centers Hail, Saudi Arabia. Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. 2019;12(1). Available from: https://bit.ly/2QisBR1

Copyright © Alshammari et al., This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) https://creativecommns.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use distribution and reproduction in any medium, provide the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing globally in both developed and developing countries (Rani et al., 2008). It is estimated that the number of patients with DM will be doubled by 2025 (Rathmann and Giani, 2004). It has been reported that Saudi Arabia with a high prevalence of 24% was ranked 7th out of the top 10 countries for the prevalence of DM among people aged 20-79 years. Worldwide, DM being a leading cause of blindness due to its ocular complications (Sami et al, 2018). Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the most common microvascular complication of diabetes. It is the foremost cause of blindness in working aged people as well as patients aged 55 years or older (Bunce and Wormald, 2006). DR is considered a signifi cant blinding disease. It is included in the disease control strategy of the VISION 2020 initiative. It has been estimated that 84.5% of people with DM who have had the disease for >20 years will develop DR (UKPDS, 1998; Fong et al, 2004). In a national study in Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of DR was found to be 19.7%,whereas other studies suggested a prevalence ranging from 16.7% to 31%. Both type 1 and type 2 DM can lead to DR. DR is classifi ed into two types: nonproliferative and proliferative. The former type may cause impaired vision if the macula is affected. Proliferative DR can also result in blindness, and it is more serious (Sami et al, 2018).

Knowledge about DM and DR along with their health impacts and treatments may be considered vital in motivating people to pursue appropriate eye care. Therefore, it may assist in dealing with visual impairment (Huang et al, 2013; Wang et al, 2008; Muecke et al, 2008). Despite the well documented importance and magnitude of the issue in the literature, limited studies have explored the knowledge about DR among the patients with DM. Worldwide, studies have focused on prevalence, screening and the effects of DR. DM and DR are continuously growing problems in the Saudi population and cause socioeconomic burdens for the healthcare system (Çetin et al, 2013; Seneviratne and Prathapan, 2016).

The health burden due to DM in Saudi Arabia is predicted to rise to catastrophic levels, unless a wideranging epidemic control program/multidisciplinary approach is incorporated, with great emphasis laid on advocating a healthy diet, including exercise and active lifestyles, and weight control. To properly manage DM in Saudi Arabia, a multidisciplinary approach is required in which the general health practitioners play an important role (Al Ghamdi et al, 2017). The present study was aimed to assess the level of awareness of knowledge, awareness and practices of physicians in Primary-Care Centers Hail, Saudi Arabia.

Material and Methods

The study was a cross-sectional and descriptive. This study was conducted to assess the KAP of practitioners toward DR in Primary-Care Centers Hail, Saudi Arabia. Responses were obtained by using a semi-structured multi-point questionnaire that was prepared in English and Arabic. It consisted of open and closed-ended questions. To ensure clarity of the fi nal questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted. The fi nal questionnaires were consisted demographic data and general questions about the respondents as well as questions on knowledge & awareness levels. It did not include personal details of the respondent. The written consent from respondent is taken before handover the survey questionnaire. Also an

ethical committee approval was taken from the ethical committee of the institute before starting this work.The collected data were coded and entered on a spreadsheet. Statistical analysis was performed using version 16.0. version (SPSS Inc., Chicago) statistical software.

Results

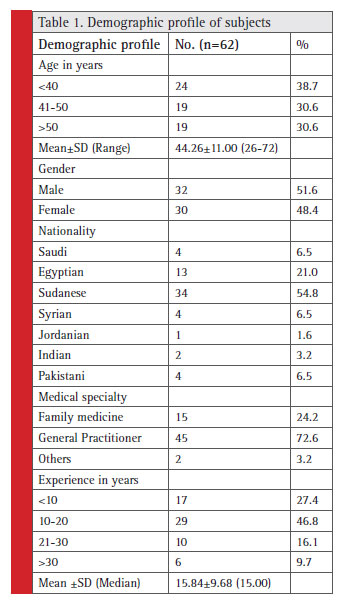

A total of 62 subjects were included in the study. More than one third of subjects were <40 years of age with mean age of 44.26±11.00 ranging from 26-72 years. About half of the subjects were males (51.6%). More than half of the subjects were Sudanese (54.8%). Majority of the subjects were general practitioner (72.6%). More than one third of subjects were practicing for 10-20 years (46.8%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Demographic profi le of subjects |

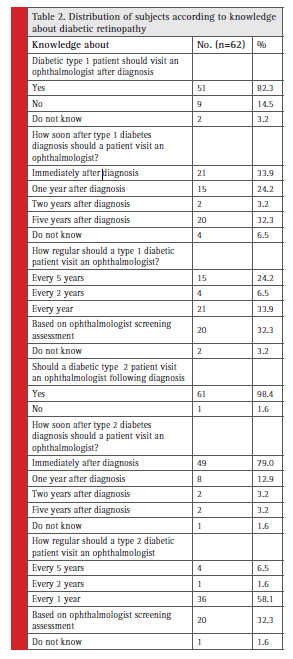

Table 2 depicts the distribution of subjects according to knowledge about diabetic retinopathy. Majority viewed that diabetic type 1 patient should visit an ophthalmologist after diagnosis (82.3%). About one third of the subjects opined that patient should visit an ophthalmologist immediately after diagnosis and every year (33.9%). Majority of the subjects viewed that type 2 patient should visit an ophthalmologist following diagnosis (98.4%). Majority of the subjects also viewed that after type 2 diabetes diagnosis, patient should visit an ophthalmologist immediately after diagnosis (79%). More than half of subjects viewed that type 2 diabetic patient should visit an ophthalmologist every one year (58.1%).

|

Table 2: Distribution of subjects according to knowledge about diabetic retinopathy |

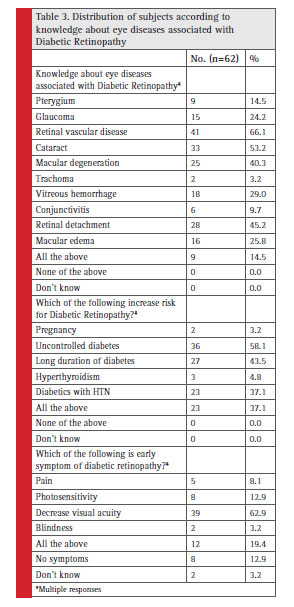

Retinal vascular disease was reported as the most common eye disease associated with diabetic retinopathy (66.1%). Cataract was reported as the second most common eye disease associated with diabetic retinopathy (53.2%). Retinal detachment was reported as the third most common eye disease associated with diabetic retinopathy (45.2%). Uncontrolled diabetes was reported as the most common risk for diabetic retinopathy (58.1%). Long duration of diabetes was reported as the second most

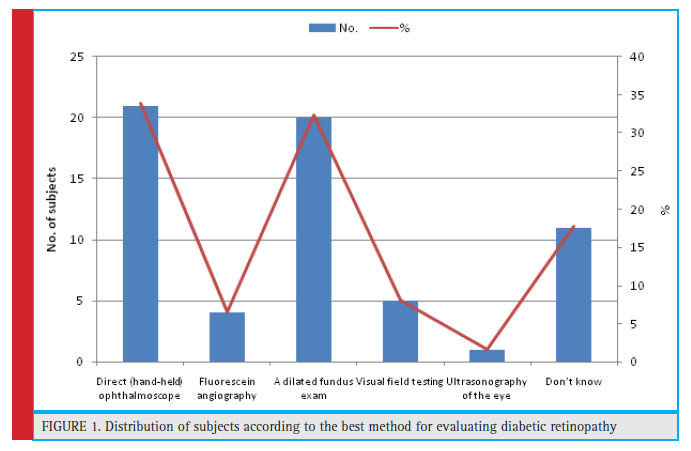

common risk for diabetic retinopathy (43.5%). Diabetic with HTN was reported as the third most common risk for diabetic retinopathy (37.1%). Decrease visual acuity was the most common symptom of diabetic retinopathy (62.9%) (Table 3). About one third of the subjects adapted direct (hand-held) ophthalmoscope and a dilated fundus exam for evaluating diabetic retinopathy each constituting 33.9% and 32.3% respectively. The percentage of the other methods was less than 10% (Fig. 1).

|

Figure 1: Distribution of subjects according to the best method for evaluating diabetic retinopathy |

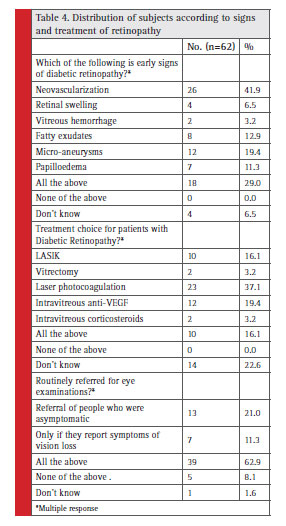

Table 4 shows the distribution of subjects according to signs and treatment of retinopathy. Neovascularization was reported as the most common early signs of diabetic retinopathy (41.9%). Micro-aneurysms was reported as the second most common early signs of diabetic retinopathy (19.4%). Intra vitreous anti-VEGF (37.1%) was the most common treatment choice among the subjects. More than half of subjects referred both people who were asymptomatic and only if they reported symptoms of vision loss (62.9%) (Table 4).

|

Table 3: Distribution of subjects according to knowledge about eye diseases associated with Diabetic Retinopathy |

|

Table 4: Distribution of subjects according to signs and treatment of retinopathy |

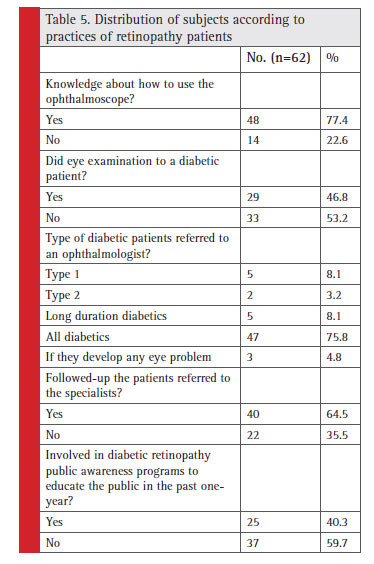

Majority of the subjects had knowledge about using ophthalmoscope (77.4%) and 46.8% did eye examination to a diabetic patient. Majority of subjects referred all diabetic patients to an ophthalmologist (75.8%). More than half of subjects followed-up referred patients (64.5%). More than one third of patients were involved in the diabetic retinopathy public awareness programs to educate the public in the past one-year (40.3%)

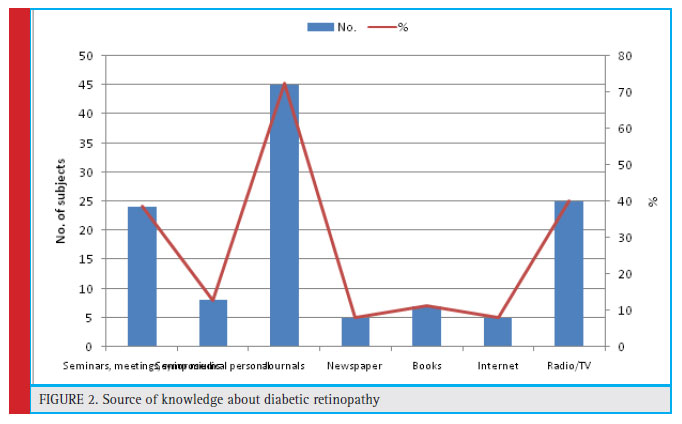

(Table-5). Journals was the main source of knowledge about diabetic retinopathy (72.6%) followed by Radio/ TV (40.3%), Seminars, meetings, symposiums (38.7%), senior medical personal (12.9%), books (11.3%) and newspaper & internet (8.1%) (Fig.2).

|

Figure 2: Source of knowledge about diabetic retinopathy |

Discussion

almost equal practice for rural and urban situations which makes it a good representative of the Saudi community.In the present study, more than one third of subjects were <40 years of age with mean age of 44.26±11.00ranging from 26-72 years. About half of the subjects were males (51.6%). More than half of the subjects were Sudanese (54.8%). Majority of the subjects were general practitioner (72.6%). More than one third of subjects were practicing for 10-20 years (46.8%).

Majority of the subjects were general practitioner (72.6%) and more than one third of subjects were practicing for 10-20 years (46.8%) in this study. Al Ghamdi et al (2017) reported that most of the physician had short periods of practice and were more specialized in discipline rather than family medicine and only one third had special training in diabetes and DR management.

The majority of the physicians had adequate knowledge about DR and followed national and international guidelines for its management. Most of the physician were well aware about consequences of DR. They knew that the ideal method of examination was ophthalmoscopy. However, this was not practiced by many. Here, there was a disparity between knowledge level and practice pattern. The gap between knowledge and practice in DR screening has been reported (Sparrow et al, 1993). This study neither elucidated the barriers that block the physician from putting their knowledge into practice, or the ways to close this evidence-practice gap.

|

Table 5: Distribution of subjects according to practices of retinopathy patients |

Although a signifi cant percentage of the physician had limited knowledge about the importance of diabetic retinopathy risk factors. Lack of hands on training courses could be an important reason and that needs to be investigated. Ophthalmoscopes are considered basic equipment that is regularly supplied by the Ministry of Health to primary health care practice. Shortage in ophthalmoscopes in PHCs refl ects some lacunae in health care system. Individual practitioners can consider getting their own ophthalmoscope, which will greatly improve the quality of their work. Once the infrastructure is available, it need not be a problem for the physician to put their knowledge into practice.

Conclusion

This study displays the need for hands on training of physician about detection of DR by direct use of ophthalmoscopes. Barriers for ophthalmoscope examination as perceived need to be further addressed and evaluated. Furthermore, It is of great importance to improve the screening facilities at the primary health care setting. This study also suggested that all stakeholders including policymakers and especially health providers should prioritize building awareness. In addition, all available and feasible resources should be channeled towards reducing the burden of diabetic retinopathy.

References

Rani, P, Raman, R, Subramani, S. (2008) Knowledge of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy among rural populations in India,

and the infl uence of knowledge of diabetic retinopathy on attitude and practice. Rural Remote Health; 8: 838.

Rathmann, W, Giani, G. (2004) Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care; 27: 2568–2569.

Sami H. Alzahrani, Marwan A. Bakarman, Saleh M. Alqahtani et al. (2018) Awareness of diabetic retinopathy among people with diabetes in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. TAEM; 9 (4).

Bunce, C, Wormald, R. (2006) Leading causes of certifi cation for blindness and partial sight in England & Wales. BMC Public Health; 6: 58.et

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. (1998) Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications

in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet; 352: 854–865.

Fong, DS, Aiello, L, Gardner, TW. (2004) Retinopathy in diabetes. Diabetes Care; 27(Suppl. 1): S84–S87. Huang, OS, Zheng, Y, Tay, WT. (2013) Lack of awareness of common eye conditions in the community. Ophthalmic Epidemiol; 20: 52–60.

Wang, S, Tikellis, G, Wong, N. (2008) Lack of knowledge of glycosylated hemoglobin in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract ; 81: e15–e17.

Muecke, JS, Newland, HS, Ryan, P. (2008) Awareness of diabetic eye disease among general practitioners and diabetic patients in Yangon, Myanmar. Clin Exp Ophthalmol; 36: 265–273.

Çetin, EN, Zencir, M, Fenkçi, S. (2013) Assessment of awareness of diabetic retinopathy and utilization of eye care services among Turkish diabetic patients. Prim Care Diabetes; 7: 297–302.

Seneviratne, B, Prathapan, S. (2016) Knowledge on diabetic retinopathy among diabetes mellitus patients attending the Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Sri Lanka. J US China Med Sci; 13: 35–46.

Al Ghamdi A, Rabiu M, Al Qurashi AM, Al Zaydi M, Al Ghamdi AH, Gumaa SA, Althomali TA, Al Ghamdi AN. (2017) Knowledge, attitude and practice pattern among general health practitioners regarding diabetic retinopathy Taif, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Sci; 6:44-51

Sparrow JM, McLeod BK, Smith TD, Birch MK, Rosenthal AR. (1993) The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy

and their risk factors in the non-insulin-treated diabetic patients of an English town. Eye (Lond); 7(Pt 1):158-63.