Investigating the effectiveness of play therapy

in improving cognitive-behavioral symptoms of

autistic disorder

Samira Hatami

1

and Fatemeh Rahmani

2

1

MA in General Psychology, Azad University of Torbat-e-Jam, Iran

2

Master of Clinical Psychology, Kharazmi University of Tehran, Iran

ABSTRACT

This study aims to determine the effectiveness of play therapy in improving cognitive-behavioral symptoms of

autism. The present research is a pretest-posttest quasi-experimental study design with two experimental and control

groups. The statistical population consists of all children with autistic disorder in Mashhad in the year 2009-2010. The

subjects (30 boy children with autism) were selected from Tabassom educational center for autistic children through

available sampling method and were randomly assigned into two experimental and control groups, each including

15 participants. To this end, a pretest was initially administered for both groups using Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (CARS) and then, play therapy was conducted for twelve 45-minute sessions with the experimental group and

nally, a posttest was implemented. In analyzing the data, analysis of covariance was applied. The research ndings

demonstrated that at the end of play therapy sessions, the experimental group compared to the control group showed

signi cant reduction in total scores obtained in Childhood Autism Rating Scale (P=0.05). In other words, play therapy

is effective in improved cognitive-behavioral symptoms of autistic disorder.

KEY WORDS: PLAY THERAPY, COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL SYMPTOMS, AUTISTIC DISORDER

249

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author:

Received 27

th

Dec, 2016

Accepted after revision 2

nd

March, 2017

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2017: 4.31 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2017. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. Special Issue No 1:249-254 (2017)

INTRODUCTION

We live in an age when children’s disorders and diseases

are considered by families, specialists and health systems

more than any other time. A child who is born has the

highest and fullest growth potential. He is created at his

best and has the readiness and capacity to be trained in

the most appropriate way and achieve the highest per-

fections. Children’s nervous system like adults’ nervous

system has not reached full development since growth

continues and in other words, children are changing and

evolving; thus, their behavior is always changing. Given

250 INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAY THERAPY BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Samira Hatami and Fatemeh Rahmani

that children depend heavily on parents and others and

are immature in terms of physical and mental capabili-

ties, the only thing they can do in the face of pressures

and discomforts is the incidence of behavioral disorders.

Indeed, the child’s behavior is his expressive language.

The more problems the child experiences in associa-

tion with others and expression of his own feelings and

needs, the greater his mental and behavioral disorders

will be (Glus, 1998; translated by Jamalfar, 1998).

Among exceptional children, autistic children have a

highly sensitive place. Fast and accurate detection and

diagnosis and subsequently treatment of such children

are of crucial importance. Man has failed to de nitively

treat this disorder; even in many cases, these patients

are not diagnosed. For this reason, it is often thought

that this disease is not highly prevalent. Parents of autis-

tic children are willing to know why their child is not

able to properly speak and communicate with peers and

people or play with age-appropriate toys. The question

is whether or not the incidence of these disorders is con-

genital. Accordingly, they seek treatment for their child’s

disease (Rafe’ei, 2006).

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Pervasive developmental disorder is a term that is cur-

rently used to refer to severe psychological problems

that appear in childhood. These disorders embrace seri-

ous disturbance in cognitive, social, behavioral and

emotional development of the child, which have broad

consequences and effects on the growth process. In

this group of diseases, social skills, language develop-

ment and behavioral repertoire either have not properly

developed or have been lost in early childhood (Kaplan,

Sadok & Gerb, 1987; translated by Fazel & Karimi, 1996).

Autistic children show impairment in social interac-

tion in several ways. Their nonverbal behaviors indicate

emotional distance which is characterized by avoidance

of making eye contact, strange facial effects and use

of special gestures to control interactions. Unlike most

children who like to play with other children, these chil-

dren avoid establishing relationships with peers. They

resist their parents’ hugging and fondling in childhood.

Autistic children are not able to talk or show too much

delay in language acquisition (Haldgin & Witborn, 1997;

translated by Seyyed Mohammadi, 2007).

Play therapy is also one of the effective methods in

the treatment of children’s behavioral and mental prob-

lems. Playing has a great impact on the child’s growth.

In fact, playing is a natural instrument for the child to

express “himself” and his feelings, establish communi-

cation, describe experiences, reveal the wishes and reach

self-actualization (Landreth, 1985; translated by Arian,

1995).

By reviewing the theoretical background and studies

conducted on the subject, it can be found that although

multiple investigations have been carried out about

variables of the subject and their relationship with one

another, few studies have been conducted on the effect

of play therapy on cognitive-behavioral symptoms of

disorders including autism pervasive developmental dis-

order. Further, in this eld, there is no research that has

directly addressed the effectiveness of play therapy in

improving cognitive-behavioral symptoms of autistic

disorder. Therefore, with regard to the above framework,

the researcher in the present study seeks to answer this

fundamental question as to “whether play therapy is

effective in improving cognitive-behavioral symptoms

of autism”.

RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS

Play therapy is effective in improving cognitive-behav-

ioral symptoms of autistic children.

RESEARCH VARIABLES

Independent variable: In this study, play therapy

is the independent variable.

Dependent variable: Cognitive-behavioral symp-

toms of autistic children are considered as the

dependent variable.

Control variable: In this study, age and gender are

regarded as the control variables. Intervening vari-

able: In this study, mental retardation, hyperactiv-

ity and other associated disorders are considered

as the intervening variables.

De nitions of terms Theoretical de nitions of vari-

ables Theoretical de nition of play therapy: Play ther-

apy is a form of psychotherapy that is used for young

children in response to their limited ability to express

oneself verbally (Levinger, 1994).

Theoretical de nition of cognitive-behavioral

symptoms of autistic disorder: These symptoms com-

prise the inability to mutually communicate with others

from early in life, having fun with objects rather than

humans, compulsive behavior in the face of changes,

impaired verbal communication and cliché and repeti-

tive behaviors (Aksline, 1997; translated by Mozayyani;

Nowzar Adan, 1989).

Theoretical de nition of autism: It is a severe dis-

ability that occurs in the rst 3 years of life and is

caused by the neurological disorder that affects brain

function (Rafe’ei, 2006). Operational de nitions of vari-

ables Operational de nition of play therapy Passive play

therapy techniques which include 13 activities are used

during 12 sessions of 45 minutes for the subjects of the

experimental group.Operational de nition of cognitive-

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAY THERAPY 251

Samira Hatami and Fatemeh Rahmani

behavioral symptoms of autistic disorder. It is the score

obtained by the individual in Childhood Autism Rating

Scale.

Operational de nition of autism: It starts at age 3 and

is characterized by having at least 6 cases of the features

mentioned in DSM-IV-TR. Checklist of Autism in Tod-

dlers (CHAT) can also be used.

Research type: This research is a quasi-experimental

study in which attempt has been made to control the

intervening variables to the extent possible.

Research design: This study is a pretest-posttest

quasi-experimental design with two experimental and

control groups.

RT

1

X

1

T

2

RT

3

T

4

Statistical population and sample: The research sta-

tistical population consists of all children with autism in

Mashhad in the year 2009-2010. The statistical sample

comprises 30 individuals (15 subjects in the experimen-

tal group and 15 subjects in the control group) from

among autistic boy children aged 5 to 13 years in Tabas-

som educational center for autistic children.

COMMUNICATION WITH PEOPLE

1. No evidence of forms of abnormality in commu-

nication with people: The child’s behavior is ap-

propriate to his age. When he is asked to do some-

thing, he may seem a little bit shy, fastidious or

upset; but it not abnormal. -1.5

2. Mildly abnormal communications: The child may

avoid eye contact with adults. He may keep aloof

from adults or become disturbed if he is forced to

interact. He may be greatly shy. He does not re-

spond normally to adults and is more attached to

his parents than the children of his age. -2.5

3. Moderately abnormal communications: The child

sometimes stays away from adults or it seems that

he is unaware of what adults do. Sometimes con-

tinuous and emphatic effort is essential to attract

the child’s attention. -3.5

4. Severely abnormal communications: The child

constantly avoids adults or is unaware of what

adults do. In contact with adults, he is almost nev-

er the initiator. Continuous effort is needed to at-

tract the child’s attention.

IMITATION

1. Appropriate imitation: The child can imitate the

sounds, words and movements according to his age and

skill level. -1.5 2. Mildly abnormal imitation: The child

imitates simple behaviors like clapping or monophonic

sounds. Sometimes he imitates after stimulation or with

little delay. -2.5 3. Moderately abnormal imitation: The

child only sometimes imitates and for this purpose, help

and insistence of adults are needed. He mostly imitates

with little delay. -3.5 4. Severely abnormal imitation: The

child rarely or never imitates the sounds, words or move-

ments unless with the stimulation and help of adults.

EMOTIONAL RESPONSE

1. Emotional responses appropriate to age and situation:

Type and degree of the child’s emotional responses are

appropriate and are determined by changes in his facial

expression, gesture and behavior. -1.5 2. Mildly abnormal

emotional responses: Type and degree of the child’s emo-

tional responses are sometimes appropriate. Reactions are

not usually associated with the objects or events around

him. -2.5 3. Moderately abnormal emotional responses:

Type and degree of the child’s emotional responses are

quite inappropriate. Reactions may be totally limited or

very severe and without any association with the situa-

tions. The child may mimic, laugh or become in exible

while there is no object or event explicitly causing this

issue. -3.5 4. Severely abnormal emotional responses:

Responses are rarely appropriate to the situation. When

the child has a stable temperament, it is very dif cult to

change it. Conversely, the child may show completely dif-

ferent feelings while nothing has changed.

BODY MOVEMENTS

1. Body movements appropriate to the age: The child can

move as easily and quickly as the children of his own

age. -1.5 2. Mildly abnormal body movements: Some

strange states such as clumsiness, repetitive movements,

poor coordination or rarely unusual movements may

exist. -2.5 3. Moderately abnormal body movements:

The child’s behaviors are quite strange and unusual

with regard to his age and include strange nger move-

ments, strange nger position or body gesture, staring

at the body, spontaneous aggression, wiggling, squirm-

ing, repetitive movements of the ngers and walking

on toes. -3.5 4. Severely abnormal body movements:

Severe or persistent movements of the above suggest

very abnormal body movements. These behaviors may

persist despite the efforts to prevent them or involving

children in other activities.

CHANGE ADAPTATION

1. Age-appropriate response to change: If the child nor-

mally notices changes or he is reminded, he accepts with

no insistence. -1.5 2. Mildly abnormal change adapta-

tion: If adults try to change the child’s tasks, he may

do the same activity or apply the same thing. -2.5 3.

Samira Hatami and Fatemeh Rahmani

252 INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAY THERAPY BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Moderately abnormal change adaptation: The child usu-

ally resists changes and tries to do the old jobs so that

it is dif cult to dissuade him. If his xed and daily rou-

tines change, he may become upset and angry. -3.5 4.

Severely abnormal change adaptation: The child shows

severe reactions to change. If he is forced to adapt him-

self to the change, he becomes furious and does not

cooperate and his response is accompanied by turmoil.

IMPLEMENTATION METHOD

To do this research, after coordination carried out by the

University with Mashhad Bureau of Exceptional Educa-

tion, we were introduced to Tabassom educational center

for autistic children. It should be noted that comprehen-

sive diagnostic evaluation of autistic children was done

in two stages:

First stage: Preliminary diagnosis or initial assess-

ment

In this stage, child development screening test is per-

formed. Parents’ observations and information about

child development and its history can greatly help in

this step. Some of the screening tools which collect data

about the child’s social development and communica-

tion skills are as follows:

1. Checklist of Autism in Toddlers (CHAT)

2. Screening Tool for Autism in Two-Year-Olds

(STAT)

3. Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) for

children of 4 years and older

4. PDD assessment Scale/Screening Questionnaire

(ASSQ)

If suspicious signs of a problem or disorder are observed

in the diagnosis phase or initial assessment, the child is

referred for comprehensive diagnostic evaluation.

Second stage: Comprehensive diagnostic evalua-

tion: This evaluation is performed by a group of spe-

cialists including child psychiatrist, neurotourist, occu-

pational therapist and speech therapist. In this stage,

Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R) which is a struc-

tured interview is completed with the help of the child’s

parents or caregiver. Additionally, CARS tool can be

applicable.In this study, 30 children were selected as

the sample through available sampling method. After

randomly assigning the subjects into the experimental

(n=15) and control (n=15) groups, the two groups took

a pretest using Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS).

Play therapy was passively implemented for the subjects

of the experimental group during 12 sessions of 45 min-

utes (3 sessions per week). At the end of play therapy, a

posttest was taken from both groups.

INFERENCE OF DATA

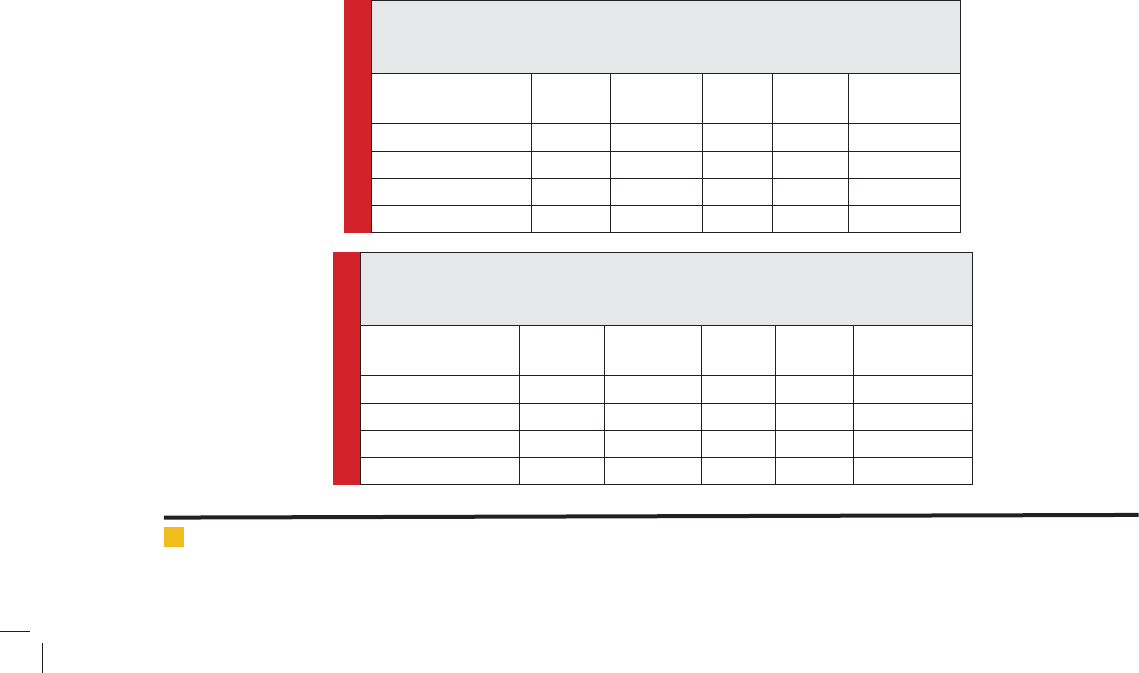

It can be observed in the above table that F coef cient to

compare the mean posttest score of the rst cognitive-

behavioral symptom of autism (communication with

people) in the experimental and control groups (after

controlling the pretest scores) was calculated to be 0.96

which is not statistically signi cant (P

0.05) and thus,

the null hypothesis is accepted and it is concluded that

the implementation of play therapy has no signi cant

in uence on improving the rst component of Child-

hood Autism Rating Scale (communication with people).

Table 1: Results obtained from covariance analysis of the experimental

group with the control group in the rst component of Childhood Autism

Rating Scale (communication with people)

Analysis of

covariance factors

Sum of

squares

Degree of

freedom

Mean

Square

F value Signi cance

level

Pretest 7.14 1 7.14 162.47 0.000

Intergroup 0.04 1 0.04 0.96 0.34

Error 1.18 27 0.043

Total 8.46 29

Table 2. Results obtained from covariance analysis of the experimental group

with the control group in the second component of Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (imitation)

Analysis of

covariance factors

Sum of

squares

Degree of

freedom

Mean

Square

F value Signi cance

level

Pretest 8.10 1 8.10 193.39 0.000

Intergroup 0.08 1 0.08 1.92 0.17

Error 1.31 27 0.04

Total 9.36 29

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAY THERAPY 253

Samira Hatami and Fatemeh Rahmani

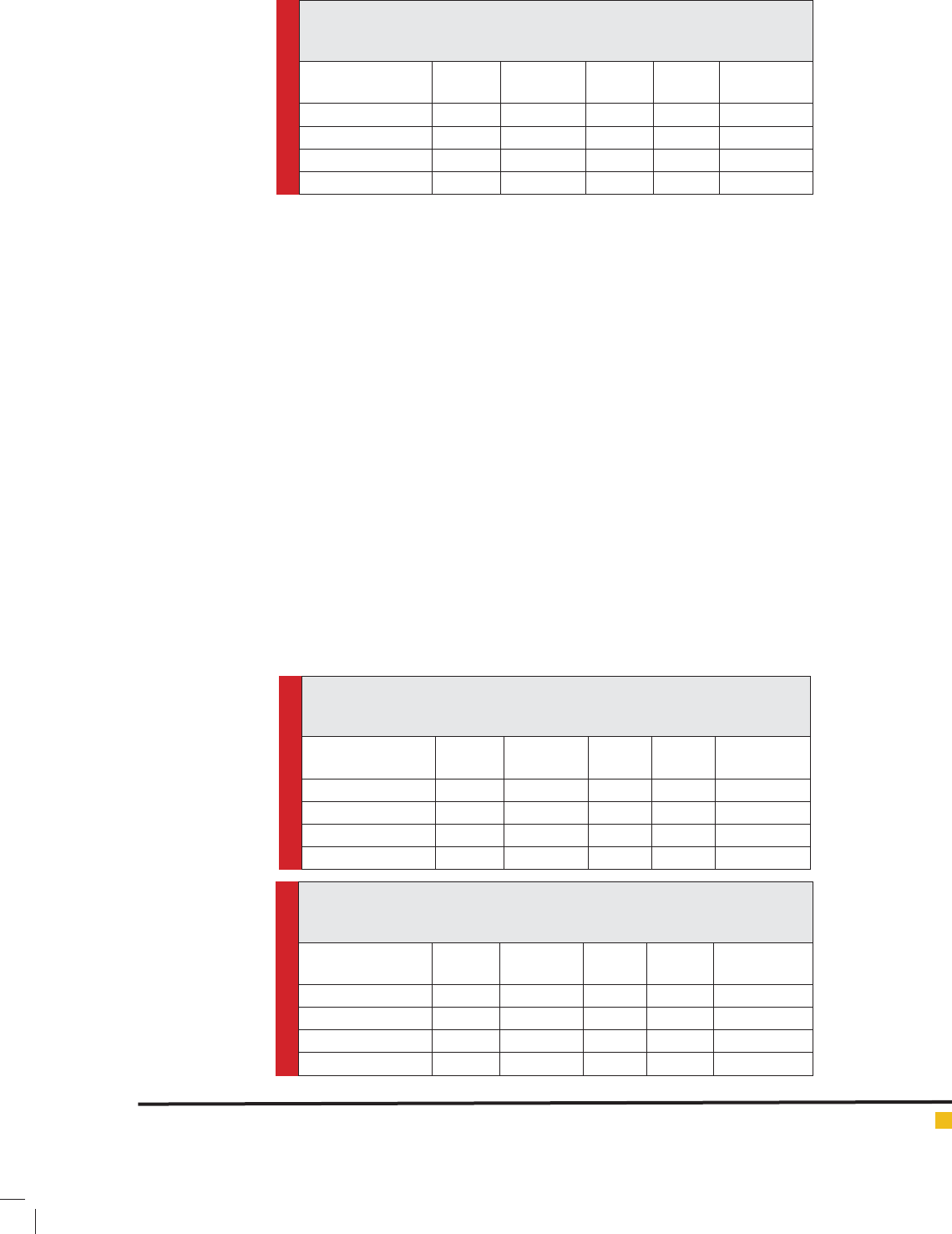

Table 3. Results obtained from covariance analysis of the experimental group

with the control group in the third component of Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (emotional response)

Analysis of

covariance factors

Sum of

squares

Degree of

freedom

Mean

Square

F value Signi cance

level

Pretest 2.98 1 2.98 31.66 0.000

Intergroup 0.003 1 0.003 0.003 0.95

Error 2.54 27 0.094

Total 5.74 29

Table 4. Results obtained from covariance analysis of the experimental group

with the control group in the fourth component of Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (body movements)

Analysis of

covariance factors

Sum of

squares

Degree of

freedom

Mean

Square

F value Signi cance

level

Pretest 5.74 1 5.74 104.24 0.000

Intergroup 1.89 1 1.89 0.000 0.98

Error 1.48 27 0.05

Total 7.24 29

Table 5. Results obtained from covariance analysis of the experimental group

with the control group in the fth component of Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (change adaptation)

Analysis of

covariance factors

Sum of

squares

Degree of

freedom

Mean

Square

F value Signi cance

level

Pretest 6.19 1 6.19 70.56 0.000

Intergroup 0.31 1 0.31 3.60 0.06

Error 2.37 27 0.08

Total 8.57 29

It can be seen in the above table that F coef cient

to compare the mean posttest score of the second cog-

nitive-behavioral symptom of autism (imitation) in the

experimental and control groups (after controlling the

pretest scores) was calculated to be 1.92 which is not

statistically signi cant (P

0.05) and hence, the null

hypothesis is accepted and it is concluded that the imple-

mentation of play therapy has no signi cant impact on

improving the second component of Childhood Autism

Rating Scale (imitation).

It can be seen in the above table that F coef cient to

compare the mean posttest score of the third cognitive-

behavioral symptom of autism (emotional response) in

the experimental and control groups (after controlling

the pretest scores) was estimated to be 0.003 which is

not statistically signi cant (P

0.05) and therefore,

the null hypothesis is accepted and it is concluded that

the implementation of play therapy has no signi cant

impact on improving the third component of Childhood

Autism Rating Scale (emotional response).

It can be observed in the above table that F coef-

cient to compare the mean posttest score of the fourth

cognitive-behavioral symptom of autism (body move-

ments) in the experimental and control groups (after

controlling the pretest scores) was calculated to be 0.000

which is not statistically signi cant (P

0.05) and so,

the null hypothesis is accepted and it is concluded that

the implementation of play therapy has no signi cant

effect on improving the fourth component of Childhood

Autism Rating Scale (body movements).

It can be seen in the above table that F coef cient to

compare the mean posttest score of the fth cognitive-

behavioral symptom of autism (change adaptation) in

the experimental and control groups (after controlling

the pretest scores) was calculated to be 3.60 which is

not statistically signi cant (P

0.05) and thus, the

null hypothesis is accepted and it is concluded that the

implementation of play therapy has no signi cant effect

on improving the fth component of Childhood Autism

Rating Scale (change adaptation).

254 INVESTIGATING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PLAY THERAPY BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Samira Hatami and Fatemeh Rahmani

In the present study, it has been hypothesized that

play therapy is effective in improving cognitive-behav-

ioral symptoms of autistic disorder. With regard to data

analysis in section 4, the research ndings revealed that

after implementing the techniques of play therapy, sig-

ni cant changes have been made in the whole cognitive-

behavioral symptoms of autistic children. Evaluation of

the experimental group scores after the implementation

of play therapy suggested that there is signi cant differ-

ence between autistic children and subjects of the control

group in cognitive-behavioral symptoms and this indi-

cates that this treatment method has had a positive effect

on improving cognitive-behavioral symptoms of autism.

The results obtained from this research are consistent

with the ndings achieved in some other studies in this

regard. Thorp et al., (1995) and also McDonough et al.

(1997) in a study investigated the effects of play therapy

and puppet show on the treatment of autistic children.

The obtained results demonstrated that this method is

effective in the treatment of such children. Forest (2004)

conducted a study and showed that play therapy is an

effective method regarding the children who have expe-

rienced events or problems in life. Sarlak and Rasouli-

yan (1388) have also referred to the effectiveness of

voice therapy in increasing the rate of hearing and thus

auditory responses of autistic children.

Qaderi, Asghari Moqaddam and Sha’eiri (2006) and

Zolmajd, Borjali and Arian (2007) also examined the

impact of play therapy on children’s aggression. The

ndings indicated a reduction in the level of aggression

in these children. Salehi (2009) has studied the effect of

play therapy on reduced oppositional de ant disorder.

The research results revealed that play therapy signi -

cantly reduces the severity of symptoms of oppositional

de ant disorder.

RESEARCH SUGGESTIONS

Application of the ndings of this study in Welfare

Organization, Exceptional Education and other cent-

ers that engage in counseling for children with disorder

and use of play therapy as an effective method in the

treatment of children’s disorders. Establishment of cent-

ers and institutions having specialized and experienced

personnel and all kinds of facilities for the treatment of

these children with an emphasis on play therapy method.

Reassessment of subjects after 3 or 6 months to examine

the effectiveness and stability of results and also evalua-

tion of the sustainability of this treatment method.

REFERENCES

Ahmadayi (Talarizadeh), A. (2003). Cultivation of mental abili-

ties and elimination of learning disorders. Tehran: Mabna.

Bardideh, M. R. (1998). Autism and pseudo autism disorders.

Shiraz: Sasan.

Bahrami, H. (1982). Child Psychology. Tehran: Iran Revolu-

tionary Guards University.

Torkman, M. & Moqaddam, M. (1997). Educational games.

Tehran: Madreseh.

Khodaei Khiyavi, S. (2001). Psychology of play. Tabriz: Ahrar.

Delavar, A. (2001). Research Method in Psychology and Educa-

tional Sciences. Tehran: Virayesh.

Rafe’ei, T. (2006). Autism, evaluation and treatment. Tehran:

Danzheh.

Rezazadeh, M. (2004). The impact of Educational games on

reduced severity of symptoms of attention de cit hyperactivity

disorder. Master’s thesis. Tehran: Faculty of Educational Sci-

ences and Psychology.

Sarlak, N. & Rasouliyan, M. (2009). Voice therapy in the treat-

ment of autistic children. Exceptional Education (92): 52-54.

Seif, A. A. (1998). Change in behavior and behavior therapy:

Theories and methods. Tehran: Dowran.

Sho’arinezhad, A. A. (1998). Psychology of development. Teh-

ran: Payam Noor University.

Qaderi, N., Asghari Moqaddam, M. A. & Sha’eiri, M. R. (2006).

Investigating the ef ciency of cognitive-behavioral play

therapy in the aggression of children with conduct disorder.

Daneshvar rafter, 4 (7): 75, 84.

Qazvininezhad, H. (2006). Generalities of play therapy. Tehran:

Ayizh.

Kendall, F. S. (2003). Childhood disorders. Translated by M.

Kalantari & M. Gohari Anaraki. Esfahan: Jahad Daneshgahi.

(Date of publication in the original language, 1998).

Lot Kashani, F. & Vaziri, Sh. (1997). Child psychopathology.

Tehran: Arasbaran.

Mohammadi, M. R., Mesgarpour, B., Sahimi Izadian, A. &

Mohammadi, M. (2007). Psychological and psycho-pharma-

ceutical tests of children and adolescents. Tehran: Teimour-

zadeh.

Mahjour, S. R. (1991). Psychology of play. Shiraz: Rahgosha.

Milanifar, B. (1999). Psychology of Exceptional Children and

Adolescents. Tehran: Qomes.

Halgin, R. P. & Whitbourne, S. K. (2007). Clinical Perspec-

tives on Mental Disorders (Volume II). Translated by Y. Seyyed

Mohammadi. Tehran: Ravan. (Publication date in the original

language, 1997)