A review on the pharmagnostic evaluation of Meswak,

Salvadora persica

Deepak Kumar Sharma,

1

* K. R. Shah

2

and R. S. Dave

3

1

Department of Chemistry HVHP Institute of Post Graduate Studies and Research, Kadi, Gujarat, India

2

Department of Biotechnology, Pramukh Swami Science and H.D Patel Arts College, Kadi, Gujarat, India

3

Department of Chemistry, Arts, Science & Commerce College, Pilvai, Gujarat, India

ABSTRACT

Due to broad spectrum in physiologic diversity and their wide range of pharmacological activities, plants are playing

an important factor for the pharmaceutical industry. Meswak tree is shrub and botanically known as Salvadora persica

L. It has been used since ancient times as a chewing stick for oral hygiene. Many unique phytochemicals are naturally

present in Miswak, which are described by traditional medicine as a remedy for various disease symptoms with bene -

cial properties. The biological active compounds that are present in plants are referred as phytochemicals. These phyto-

chemicals are derived from different parts of plants such as leaves, barks, seed, seed coat, owers, roots and pulps and

thereby used as sources of direct medicinal agents. Phytochemistry describes the large number of secondary metabolic

compounds present in the plants. The plants are the reservoirs of naturally occurring chemical compounds and of struc-

turally diverse bioactive molecules. The extraction of bioactive compounds from the plants and their quantitative and

qualitative estimation is important for exploration of new biomolecules to be used by pharmaceutical and agrochemical

industry directly or can be used as a lead molecule to synthesize more potent molecules. This review includes the ana-

lytical methodologies in which extraction methods and the process of analysis for bioactive compounds present in the

plant extracts through the different Aaalytical techniques like HPLC, GC, GC, OPLC etc. and the detection of compound

by mean of FTIR, NMR, and MS.

KEY WORDS:

SALVADORA

, PHYTOCHEMISTRY, ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES, MESWAK

734

Biotechnological

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 11(4): 734-742 (2018)

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

Corresponding Authors: dbsikhwal@gmail.com

Received 15

th

Sep, 2018

Accepted after revision 21

st

Dec, 2018

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC / Clarivate Analytics USA

Mono of Clarivate Analytics and Crossref Indexed

Journal Mono of CR

NAAS Journal Score 2018: 4.31 SJIF 2017: 4.196

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, Bhopal India

2018. All rights reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

DOI: 10.21786/bbrc/11.4/26

Sharma, Shah and Dave

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

735

INTRODUCTION

Medicinal plants have been the keystone of traditional

herbal medicine amongst occupant of rural area world-

wide since old time. The therapeutic use of plants cer-

tainly goes back to the Sumerian and the Akkadian

civilizations in about the third millennium BC. Hip-

pocrates (ca. 460–377 BC), one of the ancient authors

who described medicinal natural products of plant and

animal origins, listed approximately 400 different plant

species for medicinal purposes. According to the World

Health Organization, a medicinal plant is the plant in

which one or more of its organs, contains substances

that can be used for therapeutic purposes, or which

are precursors for chemo-pharmaceutical compounds.

Medicinal plant will have chemical components that

are medically active in its parts including leaves, roots,

rhizomes, stems, barks, owers, fruits, grains or seeds,

which are employed in the control or treatment of a

disease condition. These chemical compounds or bioac-

tive components (non-nutritional) are often referred to

as phytochemicals (‘phyto-‘from Greek - phyto meaning

‘plant’) or phytoconstituents and are responsible for pro-

tecting the plant against microbial infections or infesta-

tions by pests (Doughari, et al. 2009) In present medical

world oral hygiene is one of the most important daily

routine practices for keeping the mouth and teeth clean

and prevents many health problems, (Halawany et al.

2012).

Recently, there have been considerable interest in

exploring the medicinal properties of S. persica. Metha-

nol, ethyl acetate, and diluted acetone extracts ofS. per-

sicawere screened for in vitro activity against someCan-

dida species with the extract of J. regia L. (Naumi et

al. 2009) The S. persica plant contain different ingredi-

ent which are helpful in the treatment of osteoporosis,

(Fouda et al. 2017). The aqueous extract of S. persica

leaves possesses analgesic activity and decreases car-

rageenan-induced inflammation in rat paw, (Ramadan

et al.2016). Another study has revealed that there are

5-O-caffeoylquinic acid and 4,5-O-Dcaffeoylquinic acid

present as the major phenolic compounds in the root of

S. persica while the stem is rich in 5-O-caffeoylquinic

acid, 3,5-O-Dcaffeoylquinic acid, catechin, and epicat-

echin, (Aumeeruddya et al. 2017). A high content of

5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, naringenine, and some alka-

loids, including caffeine, theobromine, and trigonelline

was also reported from the bark. A new sulphur-con-

taining imidazoline alkaloid, persicaline, along with ve

known compounds was identi ed in S. persica which

have different phytochemical activities, (Mohamed

Farag et al. 2018).

Several studies have probed into the biological pro le

of this plant and a wealth of literature has emerged and

published. In this direction we aimed to explore the up

to date data review regarding S. persica. On the basis of

this background, therefore, the purpose of this piece of

study is to provide baseline information of the effective-

ness ofS.persicastick extract in different aspects. The

phytochemical bio-application of S. persica in various

elds have also been systematically reviewed. Lastly,

possible future directions of research and priority are

also discussed.

HISTORY

According to ancient Greek and Roman literatures from

the 3500 BC, the evolution of the toothbrush may be

traced from chewing sticks that were used by Babyloni-

ans and to toothpicks that were chewed to help clean the

teeth and mouth, (Wu et al. 2001). During the old days,

the laws of Manu of ancient Vedic India stipulated that

the teeth be cleaned as part of the daily hygienic ritu-

als, (Hyson et al. 2003). This review includes the history

and the use of “Meswak” as an oral tool, as well as the

biological effects of S. persica extracts. Chewing sticks

are considered the most popular among all of the dental

care tools for their simplicity, availability, low cost and

their traditional and/or religious value (Halawany et al.

2012, Riggs el at. 2012).

Medical books of ancient India, Susruta Samhita and

Charaka Samhita, have also stressed on oral hygiene

using herbal sticks, (Dahiya et al. 2012). There are vari-

ous biological properties, including signi cant antibac-

terial, (Al-sieni et al. 2013, Rasouli et al. 2014) antifun-

gal, (Almas et al 1999) and anti-plasmodial effects in the

extract of miswak. During the 2nd century BC, the Greek

sophist, Alciphron, recommended a toothpick to clean

the ‘‘ brous residue’’ that remained between the teeth

after meals. The Greek word, karphos, Alciphron used

to describe the toothpick, is roughly translated to ‘blade

of straw’. The Romans had also used toothpicks from the

mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus). The Gospel of Buddhism

mentions Buddha receiving a ‘‘tooth stick from the god,

Sakka’’. The Talmud mentions ‘‘quesem’’, a splinter or

wooden chip that was ‘‘divided at one end by chewing

and biting’’ and used like a toothbrush.

COMMON NAME

Salvadora persica is commonly known as tooth brush

tree but it does also have various names in different

languages, in Arabic it is used to be called “Miswak”

whereas in Hindi it is known a “Meswak” or “Pillu”. The

name of any plant varies as per the geographic areas. S.

persica is well known plant in India and has many local

names which include “Gudphala” in Sanskrit, “Uka” or

“Ukaay” or “Oamai” in Tamil, “Gonimara”, “Kankhira”

Sharma, Shah and Dave

736 A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

or “Genumar” in Kanada and “Gunnangi” in Telegu.

In the western-northern area of India S. persica grows

in large number. In Gujarat people know it as “Pilludi”

or Pilu” or “Kharijal” whereas Rajasthani language has

a name “Jaal” for it. In other languages it has vener-

able names, “Khabbar” in Sindhi, “Arak” in Assamese,

“Peelu” in Punjabi, “Khakan” in Marathi. In Dutch it is

known as “Zahnbürstenbaum”, “Misvak a

g

˘acı” in Turk-

ish, “Kerriebos” in Namibia, “Asawaki, kighir” in Nigeria

and “Chigombo” or “Iremito” or “Mkayo” in Tanzania.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLANT

Traditionally rheumatism, leprosy, gonorrhoea, ulcers,

scurvy, tumours and dental diseases can be treated from

S. persica (Miswak) (Almas et al. 1995, Jindal et al.

1996). Dr. Laurent Garcin proposed the term Salvadora,

(Juan Salvadory Bosca, 1598–1681) while as persica

was oriented from Persia and L. is used to indicate Carl

Linnaeus (1707–1778), the father of modern taxonomy.

As a shrub the miswak pant has long branches, often

pendulous or semiscandent, glabrous or pubescent and

the leaves are sub succulent; blades coriaceous, landeo-

late to elliptic, occasionally orbicular, 1–3–10 cm long,

1–2–3 cm wide, rounded to acute at apex, cuneate to

subcordate at base. Flowers are small, greenish–white

with lateral and terminal panicles up to 10 cm long and

petals up-to 3 mm long. Drupes red or dark red purple

when ripe. (Malik S et al. 1987) Besides its medicinal

potentialities, it is also suitable in agroforestry systems

as a wind break and helps in land reclamation (Gururaja

GR et al. 2004, Bhatia B et al. 2000). The ripe fruits of

this tree are sweet and edible (locally called as Piloo)

and consumed by rural/tribal population. The seeds of

Salvadora yield a pale-yellow solid fat, rich in lauric and

myristic acid content which is used in making soaps,

illuminants, varnishes, paints as well as in food industry.

It is recognized as nonconventional oil seed tree crop.

TAXONOMIC POSITION

The genus Salvadora belongs to family ‘salvadoraeceae’.

It comprises three genera (i.e. Azima, Dobera and Salva-

dora) and 10 species distributed mainly in the tropical

and subtropical region of Africa and Asia. It belongs to

‘Magnoliophyta’ division which is further classi ed in

different classes in which Salvadora belong to ‘Magnoli-

opsida’. The order of plant is ‘Brassicales’.

USE AND PHYTOCHEMICALS

In Middle Eastern, some Asian and African cultures

chewing sticks are prepared from the roots and twigs

of S. persica. To prepare this type of sticks the stings or

roots are cut into pieces of 10-to 25-cm long. The sticks

of Miswak can usually be used 3–10 times daily con-

sidered as an inexpensive and an ef cient oral hygiene.

(AI-Bagieh NH et al. 1988) The Primary Health Care

Approach (PHCA) principles entirely consider the use

of Miswak. (Hyson JM el at. 2003) The use of chewing

sticks as an oral hygiene tool like Miswak, where it is

traditionally grown is encouraged and recommended by

the World Health Organization (WHO). (WHO et al. 1987)

In addition Miswak is also recommended for the teeth

whitening, the memory improving tool, the breath fresh-

ener, calming the bile, drying up the phlegm, the gums

strengthening, sharpening the vision and increasing the

appetite, (Almas et al. 2001). Antimicrobial substances

such as sulfur can be extracted from its roots and stems,

moreover Trimethylamine, benzyl isothiocyanate, Sal-

vadorine, beta cholesterol, tannins, saponines, sodium

chloride, potassium chloride, vitamin C, avonoids and

sterols are associated with anti-bacterial effects. Besides

this, the signi cant amounts of added silica can help

to remove plaque mechanically, (Almas et al.1995). In

this plant uoride is also found in measurable quanti-

ties, (Darout et al. 2000) which is easily dissolved and

released in water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PROCEDURE FOR SEARCHING INFORMATION

Relevant literature survey was done by scienti c web-

sites and tabs i.e Google Scholar, Scienti c journal.

Information was also obtained from books and e-arti-

cles. The scienti c name of the plant was validated using

The Plant List. Published review papers on S. persica

were used as guidelines to design the present study

and also to add missing data to ensure a more compre-

hensive and up-to-date review is obtained. The refer-

ence lists of review and research papers were searched

for further relevant information. Regarding the search

methodology, the following keywords were searched:

“Salvadora persica plant extraction”, (Google = 68,300

search results, Articles = 4,640).

PLANNING, DESIGN AND DESCRIPTION

OF SECTIONS

This review consists of different nine Sections cover-

ing the traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacologi-

cal properties, and bio-applications of S. persica. The

third subsection of seventh section highlights about the

extraction and separation of bioactive compounds of

Miswak plant. Section 8 and 9 include the separation

of phytochemicals in S. persica plant through different

extraction methods. The sections reviewed about the

phytochemicals and bioactivity of different compounds

Sharma, Shah and Dave

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

737

from the plant extract. The detailed antimicrobial activ-

ity of S. persica has been displayed in the section 10,

lastly, section 11 provides an overview of the potential

applications of S. persica in various elds.

PLANT MATERIAL

First the fresh plant/plant parts can be collected ran-

domly from the semi-arid or xerophytic region. The

sticks of plant are dried at 55

0

C by use of an oven for

three to four days and then cut into slices then ground

into a ne powder using a mixture grinder. The extract

of plant Miswak can be prepared by adding 40 g of the

Miswak powder to 200 ml of solvent in which water,

ethanol and hexane are preferred, in a closed container

and stored at room temperature for 48 h. The solvents

are then ltrated through a Whatman No. 1 lter paper

and allowed to evaporate at 40

0

C in an oven for 72 h.

The dried extracts are considered 100% pure and used

to prepare different concentrations by adding the same

solvents in an amount of 100, 250 and 500 g/ml. differ-

ent commercial toothpaste brands can be used to control

for all of the antimicrobial tests by making the concen-

tration of 100 g/ml by allowing to dry and ground. 250

mg of dried extract is dissolved to prepare the Miswak

mouth wash by using of 1 L of distilled water. (Moham-

mad Abhary et al. 2016)

As scrutinizing the aimed review article, it is observed

that after the collection of plant extraction is car-

ried out by different methods according to the nature

of phytochemical which are present in plant. As the

review on Miswak, some common method of extrac-

tion includes cold extraction and solvent extraction

using Soxhlet apparatus. At present a common Univer-

sal Extraction System (Buchi) is used for the purpose of

extraction.

PLANT EXTRACTION

Cold extraction method

It is reviewed that several of extraction is done by this

method because of low costing and high productivity

with ef ciency. During the process of cold extraction,

Measurable weight of dried powder is taken and respec-

tive solvents is added into conical ask then allow at

room temperature for thirty-minute then after it is kept

for seven days and during this period shaking is allowed

after each twenty-four hours for seven days. Finally

lter the extract through Whatman lter paper under

vacuum and dry it at room temperature in watch glass

dish. Note down the weight of each dish prior to drying

of the extracts and after drying too. The difference was

calculated by the weight of the extract. (Harborne et al.

1973).

Solvent extraction method

Recently the Universal Extraction System (Buchi) is used

for solvent extraction. First the dried plant powder taken

various parts placed in glass thimble for extraction pur-

pose with the use of various solvents. For each extract

the procedures are carried out for 10 cycles, and the tem-

perature is adjusted just below the boiling point of the

respective solvents. The resulting solvent extract is l-

tered, concentrated in vacuum concentrator and used to

determine the presence of phyto constituents (

Harborne

et al. 1973)

Supercritical uid extraction (SFE)

Supercritical uid chromatography (SFC) provides a

useful alternative to gas chromatography and liquid

chromatography for some plant samples which involves

use of gases as mobile phase at a temperature and pres-

sure exceeding its critical point, usually CO

2

is used and

compressing them into a dense liquid under these condi-

tions the mobile phase is neither a gas nor a liquid. The

turbid liquid is then pumped through a cylinder contain-

ing the material which to be extracted. From there, the

extract- hampered liquid is pumped into a separation

chamber where the extract is separated from the gas and

the gas is recovered for re-use. CO

2

is commonly used

because its low critical temperature, 31 °C, and critical

pressure, 72.9 atm, are relatively easy to achieve and

maintain. Solvent properties of CO

2

can be manipulated

and adjusted by varying the pressure and temperature.

The advantages of SFE are, no solvent residues left in it

as CO

2

evaporates completely, (Patil et al. 2010).

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE)

The combination of microwave and traditional solvent

extraction is simply termed as microwave extraction.

Microwave-assisted extraction is considered as the heat-

ing of solvents and plant tissue using microwave which

increases the kinetic of extraction (

Delazar et al 2012).

To remove the minute microscopic traces of moisture

present in plant cell, the extraction is heated in dried

plant material. As a result of the heating up of this mois-

ture inside the plant cell due the evaporation of moisture

occurs and generates tremendous pressure on the cell

wall. Due to the pressure the cell wall is pushed from

inside and the cell wall ruptures. Thus, from the ruptured

cells the exudation of active constituents occurs, hence

increasing the yield of phytoconstituents, (Gordy et al.

1953 and Goldman et al. 1963).

IDENTIFICATION OF PHYTOCHEMICALS

The separation of bioactive compound which are present

in the plant extract with different polarities is a chal-

lenging task for the process of identi cation and charac-

Sharma, Shah and Dave

738 A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

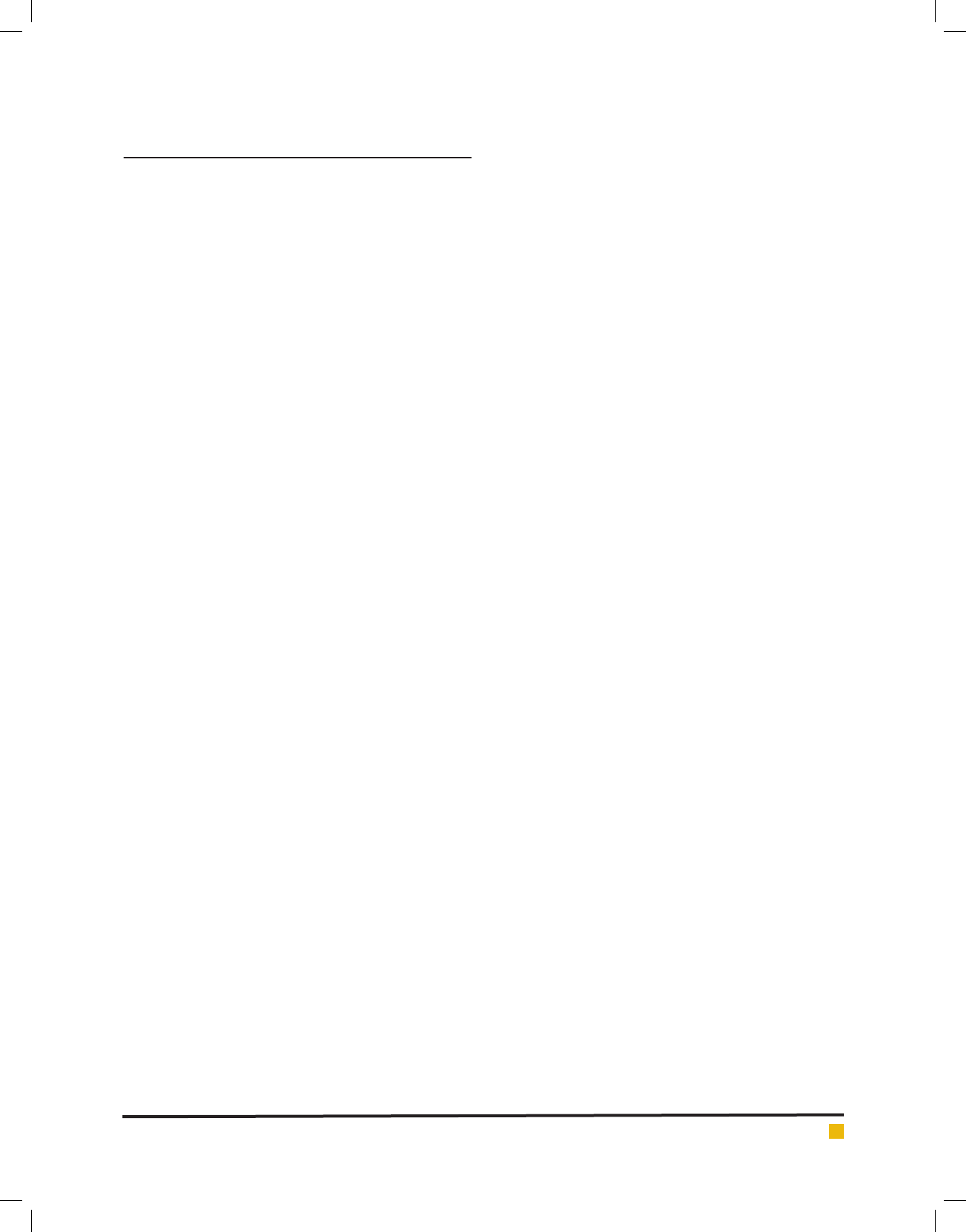

Name of Compound Chemical Structure Molecular

Weight g/mol

Molecular

Formula

PubChem

CID

Benzaldehyde 106.124 C

7

H

6

O 240

Trimethyl amine 59.112 C

3

H

9

N 1146

Benzyl isothiocyanate 149.211 C

8

H

7

NS 2346

Salvadoraside 744.74 C

34

H

48

O

18

101630443

Salvadoside 372.32 C

13

H

17

NaO

9

S 23664985

Cholesterolbeta-epoxide 402.663 C

27

H

46

O

2

108109

Sharma, Shah and Dave

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

739

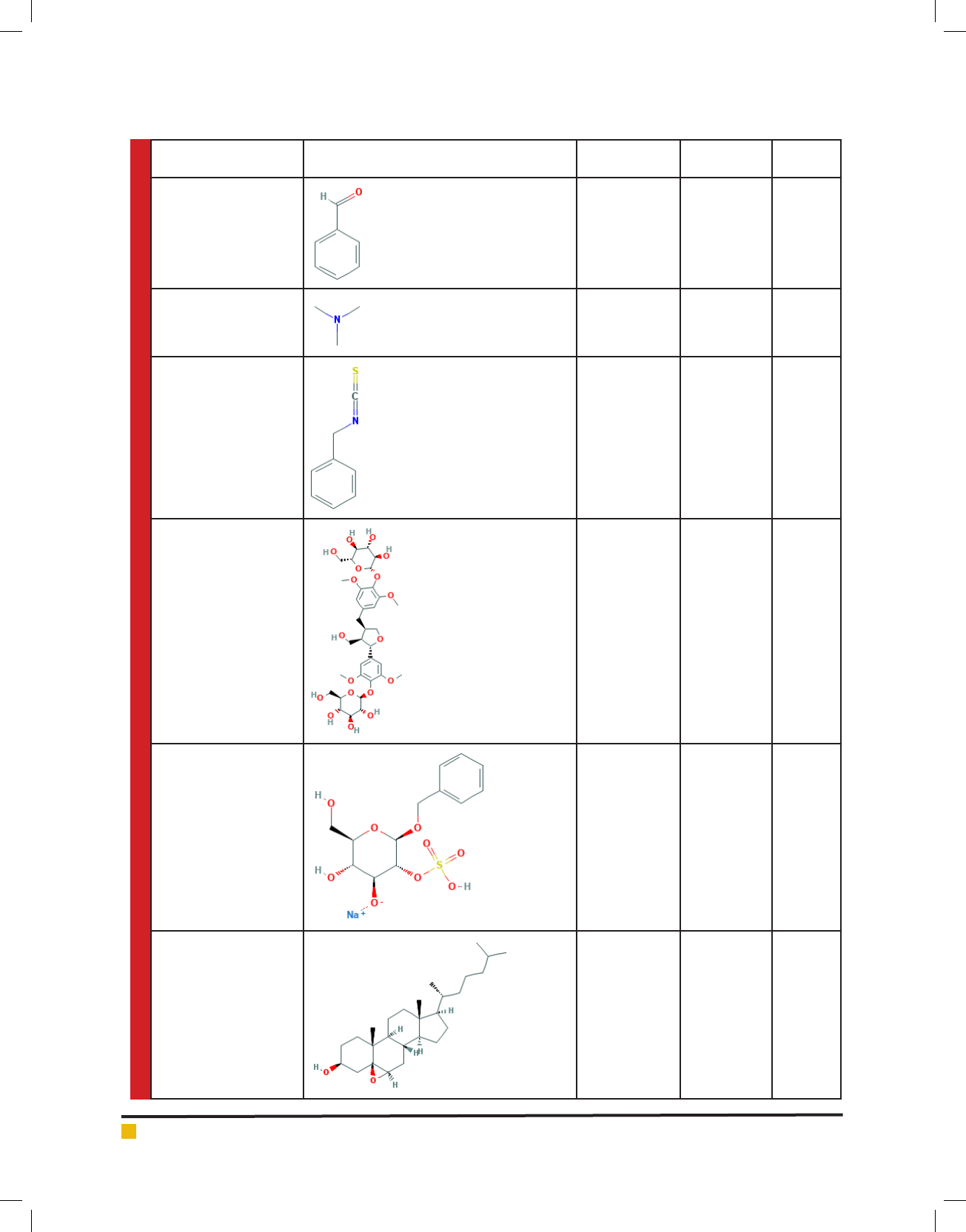

Thymol 150.221 C

10

H

14

O 6989

Theobromine 180.167 C

7

H

8

N

4

O

2

5429

N-Benzyl benzamide 211.264 C

14

H

13

NO 73878

Decane 142.2 C

10

H

22

15600

Stigmasterol 412.702 C

29

H

48

O 5280794

9-Desoxo-9-x-acetoxy-

3,8,12-tri-O-acetylingol

536.618 C

28

H

40

O

10

537583

Sharma, Shah and Dave

740 A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

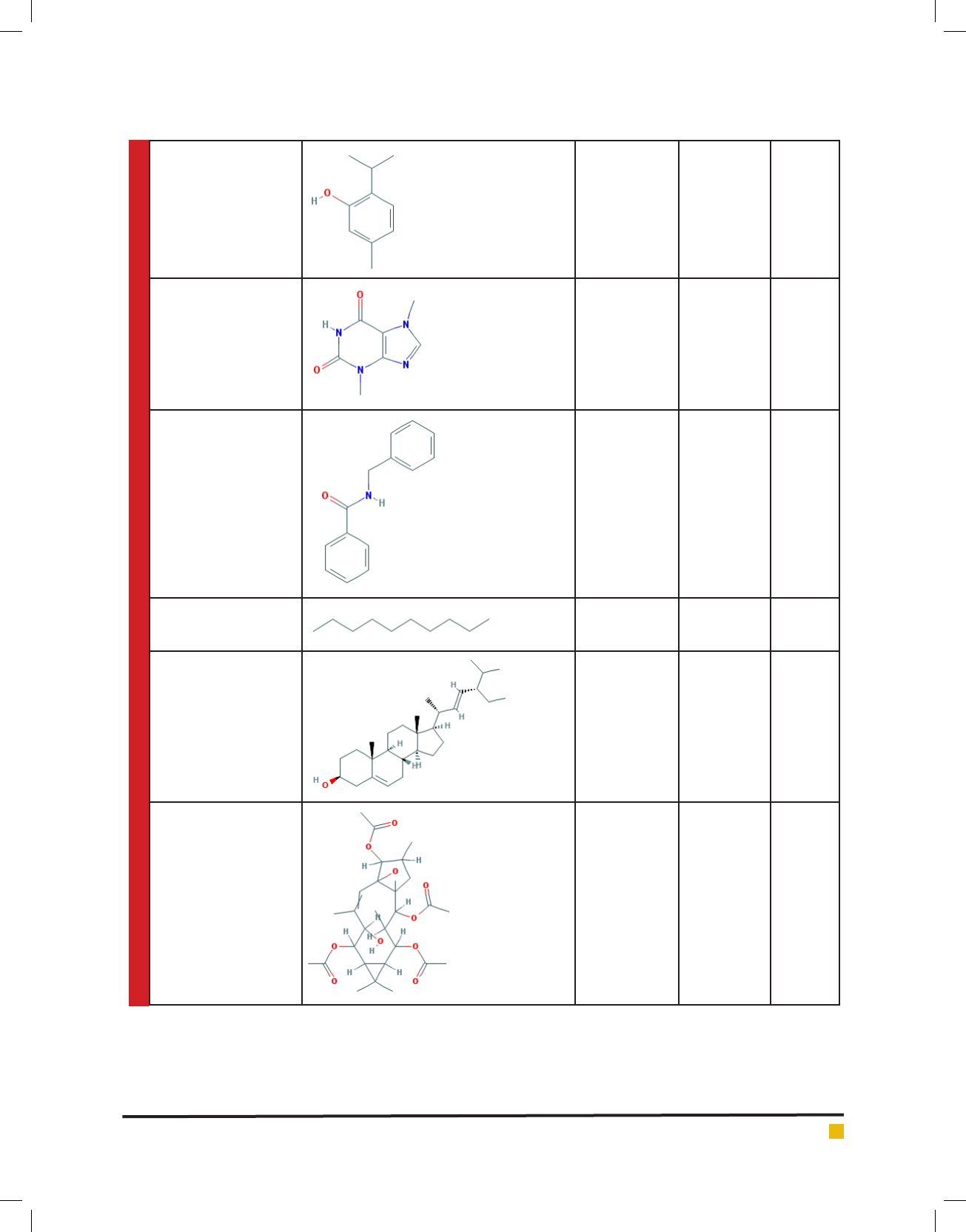

SpiculisporicAcid 328.405 C

17

H

28

O

6

316426

terization of bioactive compounds. It is a common prac-

tice to use TLC, HPTLC, paper chromatography, column

chromatography, Gas chromatography, OPLC and HPLC,

should be used to obtain pure compounds in isolation

of bioactive compounds. The pure compounds are then

used for the determination of structure and biological

activity, (Sasidharan et al. 2011).

Physicochemical and Phytochemical Studies

Phytochemical studies include extractive values, total

ash, acid insoluble ash, total sugar, starch, tannin, and

phenols can be calculated from the shade-dried and

powdered (60 mesh) plant material. (Peach K et al. 1955,

Ayurvedic Pharmacopeoeia of India. Part I et al. 2001,

2004). The Antioxidant Activity of the plant extracts

and standard was assessed on the basis of the radical

scavenging effect of the stable DPPH (2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐

picryl‐hydrazyl‐hydrate) free radical. (Verma et al 2012,

Gupta et al. 2015).

Methanol was used to make working solutions of

the test extracts. Ascorbic acid was used as the stand-

ard in solutions ranging from 1 to 50 μg/ml. In metha-

nol 0.002% DPPH solution is prepared. Then 2 ml of

this solution was mixed with 2 ml of sample solutions

(ranging from 25 μg/ml to 500 μg/ml) and the standard

solution to be tested separately. These solution mixtures

were kept in the dark for 30 min and optical density was

measured at 517 nm using a Shimadzu spectrophotom-

eter against methanol. The blank used was 2 ml of meth-

anol with 2 ml of DPPH solution (0.002%). The optical

density was recorded and percentage of inhibition was

calculated using the equation: % of inhibition of DPPH

activity = (A–B) /A × 100; where A is optical density of

the blank and B is optical density of the sample.

HPTLC STUDIES

Air dried (45-55°C) powdered stem and twig of S. persica

(2.0 g) in triplicate were extracted separately with 3 X 20

ml methanol. Extracts were concentrated under vacuum

and re dissolved in methanol, ltered and nally made

up to 100 ml with methanol prior to HPTLC analysis.

Reagents used were from Merck (Germany) and standard

ferulic acid was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Stein-

heim), (Verma et al 2012, Gupta A et al. 2015).

Antimicrobial effects

Different antimicrobial activity was performed which

can An in vitro study showed that the aqueous extract

of S. persica miswak had an inhibitory effect on the

growth of Candida albicans that may be attributed to

its high sulfate content (al-Bagieh, N. et al. 1995). Some

studies investigated the derivatives of S. persica mis-

wak using three different laboratory methods, and dem-

onstrated strong antimicrobial effects on the growth of

Streptococcus sp. and Staphylococcus aureus. (Al La ,

et al. 1995) In addition, some showed that Enterococcus

faecalis is the most sensitive microorganism affected by

the use of S. persica miswak, and noted no signi cant

difference in the antimicrobial effects of freshly cut and

1-month-old miswak. A comparison of the alcoholic and

aqueous extracts of S. persica miswak revealed that the

alcoholic extract had more potent antimicrobial activity

than did the aqueous extract (Al-Bagieh, et al. 1997).

Aqueous extract of plant inhibited all the microor-

ganisms, showing greater activity on Streptococcus spe-

cies. Methanolic extract was resisted by L. acidophilus

and P. aeruginosa. At highest concentration tested (200

mg/ml), the aqueous extract was more ef cient than the

methanolic extract but were less ef cient than the posi-

tive control streptomycin and amphotericin B. (Al-Bayati

et al. 2008) Miswak extract displayed greater reduction

in both S. mutans and Lactobacillus cariogenic bacte-

ria counts. Reduction of microbial count in females was

more for both microorganisms as compared to males,

(Bhat et al. 2012). Ethanol extract was more effective

than the aqueous extract in inhibiting the S. mutans, L.

acidophilus, E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa micro-

organisms. The aqueous extract did not display any

inhibitory effect on P. aeruginosa. (Mohammed, et al.

Sharma, Shah and Dave

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

741

2013). The miswak extracts showed comparable or

slightly stronger activity compared to some toothpastes.

The aqueous extract exhibit antibacterial activity on M.

bovis (Fallah et al., 2015).

All solvent-extracts inhibited the S. aureus, S.

mutans, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, S. salivarius, L. aci-

dophilus microorganisms. Methanol extract was more

effective than the other extracts. (Kumar et al., 2016)

S. persica aqueous extract showed higher activity than

methanol extract against S. aureus while the opposite

effect was observed against E. coli. Compared to C.

mopane and D. cinerea, S. persica was most effective

against S. aureus but was least effective against E. coli,

(Mudzengi et al., 2017).

CONCLUSION

Our literature review concludes that the use of S. per-

sica miswak as an oral hygiene aid is effective. Descrip-

tive and experimental studies have provided consider-

able evidence that the S. persica plant and its extracts

exert bene cial effects on the oral tissues and help to

maintain good oral hygiene. It is encouraging to note

the large number of studies and clinical trials that have

examined the effects of S. persica miswak and the value

that people have attached to it since ancient times. The

use of S. persica miswak alone or in combination with

conventional toothbrushes, when performed judiciously,

will result in superior oral health and hygiene. It is to

be noted that there had been earlier attempts to summa-

ries the medicinal potential of S. persica, even though

with a different or a less broad ethnopharmacological

focus. However, this review can be considered as the

rst attempt to broaden and critically assess scienti c

evidence on the ethnopharmacology of S. persica. It is

obvious from this review that S. persica can be regarded

as an important traditionally used medicinal plant har-

boring a panoply of bioactive compounds, pharmaco-

logical properties, and modern applications in emerg-

ing elds of interest. It is anticipated that this review

article will open new avenues for research and stimulate

further studies that will ll research gaps highlighted

above.

REFERENCES

Abdel-Motaal Foudaa, Amany Ragab Youssef (2017) Anti-

osteoporotic activity ofSalvadora persicasticks extract in an

estrogen de cient model of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis and

Sarcopenia, Volume-3, 132-137

Almas K. (2001) The effect of extract of chewing sticks (Sal-

vadora persica) on healthy and periodontal involved human

dentin A SEM study. Indian J Dent Res 12:127-132.

Al-Bayati, F.A., Sulaiman, K.D. (2008) In vitro antimicrobial

activity of Salvadora persica L. extracts against some isolated

oral pathogens in Iraq. Turk. J. Biol. 32 (1), 57–62.

AI-Bagieh NH, Weinberg ED. (1988) Benzylisothiocyanate:

a possible agent for controlling dental caries. Microbios Lett

39:143–51.

Al-Bagieh, N., Almas, K. (1997) In vitro antibacterial effects of

aqueous and alcohol extracts of miswak (chewing sticks). Cairo

Dent. J. 13, 221–224

Al-Bagieh, N., Idowu, A., Salako, N.O. (1994). Effect of aqueous

extract of miswak on the in vitro growth of Candida albicans.

Microbios 80 (323), 107–113.

Al-sieni AI. (2013) The antibacterial activity of traditionally

used Salvadora persica L. (miswak) and Commiphora gileaden-

sis (palsam) in Saudi Arabia. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern

Med. 11(1): 23-7.

Almas K, AI-Bagieh NH (1999) The antimicrobial effects of

bark and pulp extracts of meswak Salvadora persica Biomed

Lett 60:71–5.

Almas K, Al-La TR. (1995) The natural toothbrush. World

Health Forum 16:206-210.

Al La , T., Ababneh, H. (1995) The effect of the extract of the

miswak (chewing sticks) used in Jordan and the Middle East on

oral bacteria. Int. Dent. J. 45, 218–222.

Anonymous (2007) Ayurvedic Pharmacopeoeia of India. Part

I, Vol I. Department of Health, Ministry of Health and Fam-

ily Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi; 2004. p. 152-

165.

Anonymous (2007a) Indian pharmacopoeia, Government of

India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Controller of

Publications, New Delhi; 2007. p. 191.

Anonymous (1984) Of cial methods of Analysis (AOAC), 4th

edn. Association of Of cial Chemists, Inc. U.S.A; 1984. p. 187-

8.

Anonymous. (1972) The wealth of India - Raw materials (New

Delhi, CSIR), 1972; 9: 193-195.

Aumeeruddya, M.Z.; Zenginb, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F. A

review of the traditional and modern uses of Salvadora persica

L. (Miswak): Toothbrush tree of Prophet Muhammad. J. Eth-

nopharm. 2017, 213, 409–444.

Bhat, P.K., Kumar, A., Sarkar, S., (2012) Assessment of immedi-

ate antimicrobial effect of miswak extract and toothbrush on

cariogenic bacteria-A clinical study. J. Adv. Oral. Res. 3 (1)

13–18.

Bhatia B, Sharma HL (2000) Fuelwood production and waste-

land reclamation, Botanica 2000; 14: 84-93.

Dahiya P, Kamal R, Luthra RP, Mishra R, Saini G. (2012) Mis-

wak: a periodontist’s perspective. J Ayurveda Integr Med

3(4):184–7.

Darout IA, Christy AA, Nils Skaug, Egeberg PK. (2000) Identi-

cation and quanti cation of some potentially antimicrobial

anionic components in miswak extract. Indian J Pharmacol.

32: 11-14.

Sharma, Shah and Dave

742 A REVIEW ON THE PHARMAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF MESWAK,

SALVADORA PERSICA

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Delazar A, Nahar L, Hamedeyazdan S, Sarker SD. (2012) Micro-

wave-assisted extraction in natural products isolation. Meth-

ods Mol Biol. 864:89-115

Doughari, J.H.; Human, I.S, Bennade, S. & Ndakidemi, P.A.

(2009). Phytochemicals as chemotherapeutic agents and anti-

oxidants: Possible solution to the control of antibiotic resistant

verocytotoxin producing bacteria. Journal of Medicinal Plants

Research. 3(11): 839-848.

E.Noumi, M.Snoussi, H.Hajlaoui, E.Valentin, A.Bakhrouf.,

(2009). Antifungal properties ofSalvadora persicaandJuglans

regiaL. extracts against oralCandidastrains. European Jour-

nal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases,

E. Riggs, C. van Gemert, M. Gussy, E. Waters, N. Kilpatrick

(2012) Re ections on cultural diversity of oral health pro-

motion and prevention, Global Health Promot. 19 (1) 60–63,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1757975911429872.

Fallah, M., Fallah, F., Kamalinejad, M., Malekan, M.A.,

Akhlaghi, Z., Esmaeili, M., (2015). The antimicrobial effect of

aquatic extract of Salvadora persica on Mycobacterium bovis

in vitro. Int. J. Mycobacteriology 4, 167–168.

Goldman R. (1962) Ultrasonic Technology. Van Nostrand Rein-

hold, New York. 1962.

Gordy WWV, Smith RF Trambarulo. (1953) Microwave Spec-

troscopy. Wiley, New York. 1953.

Gupta A, Verma A, Kushwaha P, Srivastava S, Rawat AKS.

(2015) Phytochemical and Antioxidant Studies of Salva-

dora persica L. Stem & Twig. Indian Journal of Pharmaceu-

tical Education and Research | Vol 49 | Issue 1 | Jan-Mar,

2015

Gururaja GR, Nayak AK, Chinchmalatpure AR, Nath A, Babu

VP. (2004) Growth and Yield of Salvadora persica, A facul-

tative halophyte grown on saline black soil (Vertic Haplus-

tept), Arid Land Research and Management 18(1): 165-

168.

Harborne JB. (1973) Phytochemical methods. Chapman and

Hall Ltd., London. 49-88

H. Ahmad, K. Rajagopal, Biological activities of Salvadora

persica L. (Meswak), Med. Aromat. Plants 2 (4) (2013), http://

dx.doi.org/10.4172/21670412.1000129.

H.S. Halawany (2012) A review on Miswak (Salvadora persica)

and its effect on various aspects of oral health, Saudi Dent. J.

24 (2012) 63–69.

Hyson JM. (2003) History of the toothbrush. J Hist Dent

51(2):73–80.

Jindal SK, Bhansali R, Satyavir R. (1996) Salvadora tree - A

potential source of non-edible oil, In: Proc of All India seminar

on rabi oil seed crop (Jodhpur, CAZRI); 1996

Kumari, A., Parida, A.K., Rangani, J., Panda, A., (2017). Antiox-

idant activities, metabolic pro ling, proximate analysis, min-

eral nutrient composition of Salvadora persica fruit unravel

a potential functional food and a natural source of pharma-

ceuticals. Front. Pharmacol. 8 (61). http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/

fphar.2017.00061.

Malik S, Ahmed SS, Haider SI, Muzaffer A. (1987) Salvadori-

cine - a new indole alkaloid from the leaves of Salvadora per-

sica, Tetrahedron Lett 28: 163-164.

Mohammad Abhary , Abdul-Aziz Al-Hazmi. (2016) Antibacte-

rial activity of Miswak (Salvadora persica L.) extracts on oral

hygiene. Journal of Taibah University for Science 10 513–520

Mohammed, S.G., (2013). Comparative study of in vitro anti-

bacterial activity of miswak extracts and different toothpastes.

Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 8 (1), 82–88.

Mohamed Farag, Wael M. Abdel-Mageed, Omer Basudan and

Ali El-Gamal, (2018), Persicaline, A New Antioxidant Sulphur-

Containing Imidazoline Alkaloid from Salvadora persica Roots,

Molecules 23, 483; doi:10.3390/molecules2302048

Mudzengi, C.P., Murwira, A., Tivapasi, M., Murungweni, C.,

Burumu, J.V., Halimani, T., (2017). Antibacterial activity of

aqueous and methanol extracts of selected species used in

livestock health management. Pharm. Biol. 55 (1), 1054–1060.

Noumi E, Snoussi M, Hajlaoui H, Valentin E, Bakhrouf A (2010)

Antifungal properties of Salvadora persica and Juglans regia

L. extracts against oral Candida strains. Eur J Clin Microbiol

Infect Dis 29: 81-88.

Patil PS, Shettigar R.(2010) An advancement of analytical

techniques in herbal research J Adv Sci Res. 1(1):08-14.

Peach K,Tracy MV.(1955) Modern Methods of Plant Analysis.

Vol III and IV Springer, Heidelberg p. 258-61.

Ramadan, K.S., Alshamrani, S.A., (2016.) Phytochemical anal-

ysis and antioxidant activity of Salvadora persica extracts. J.

Basic Appl. Res.2, 390–395

Rasouli GAA, Rezaei A, Hosein MSS, Yaghoobee S, Khorsand

A, Kadkhoda Z, (2014) et al. Inhibitory activity of Salvadora

persica extracts against oral bacterial strains associated with

periodontitis: An in-vitro study. Journal of Oral Biology and

cranio facial research 4: 19-23.

Sasidharan S, Chen Y, Saravanan D, Sundram KM, Yoga Latha

L.(2011) Extraction, isolation and characterization of bioactive

compounds from plants’ extracts. Afr J Tradit Complement

Altern Med. 2011; 8(1):1-10.

S. Dutta, A. Shaikh (2012) The active chemical constituent and

biological activity of Salvadora persica (Miswak), Int. J. Curr.

Pharmaceut. Rev. Res. 3 (1) ISSN: 0976-822X.

Verma S, Gupta A, Kushwaha P, Khare V, Srivastava S, Rawat

AKS. (2012)Phytochemical Evaluation and Antioxidant Study

of Jatropha curcas Seeds. Pharmcog J. 4(29): 5-54.

WHO (1987) Preventive methods and programmes for oral dis-

eases. World Health Organization. Technical Report Series 713,

Geneva; 1987.

Wolf W. (1966) A history of personal hygiene – customs, meth-

ods and instruments – yesterday, today, tomorrow. Bull Hist

Dent 14(4):54–66.

Wu, C., Darout, I., Skaug, N. (2001). Chewing sticks: timeless

natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. J. Periodontal. Res. 36

(5), 275–284.