Ergonomic effects on workers of selected healthcare

areas of King Abdulaziz Medical City, National Guard

Hospital, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

Fayz Al Shahry,

1

Wejdan Mohammed Alhuwail

2

, Ghadah Mohammed Alshehri

2

, Jihan Ali

Al-Motairi

2

, Smily Jesupriya Victor Paulraj

3

*, Fatma Othman

4

and Galib Algamdi

5

1

Assistant Professor. CAMS, KSAU-HS, Consultant Neurorehabilitation Service, King Abdulaziz Medical City,

2

Student, Occupational Therapy, CAMS, KSAU-HS, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

3

Senior lecturer, CAMS, KSAU-HS, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

4

Assistant Professor CAMS, KSAU-HS, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

5

Occupational Therapy Program Manager CAMS, KSAU-HS, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

Ergonomics’ is composed of two words which are ‘ergo’ a Greek word meaning work, and ‘nomics’ which means

study. Ergonomics factors that contribute to the health are inappropriate lighting, tools design, chair design, heavy

lifting and repetitive motion and others. These factors can cause musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). The aim of this

study was to assess ergonomic effect on workers of ultrasound and microbiology areas in King Abdulaziz Medical

City, (KAMC)-Riyadh. The second objective of this study was to identify the ergonomic factors and the presence of

work related injuries, also to compare awareness of ergonomics of work sites of health workers. This study was a cross

sectional quantitative study conducted at KAMC,National Guard Hospital (NGH), the sample size for workers in radi-

ology department was 27, and the sample size for workers in the laboratory was 27. Two questionnaires distributed

among laboratory and radiology workers constructed of questions and demographic data were adapted for our study

to determine the effect of ergonomics, the most common physical problems that workers experience in their worksta-

tion, and the awareness of ergonomic among the health care workers 18 participants (40.0% of the total) from the

Microbiology-technicians were completed the questionnaire and were 27 participants (60.0%) form the Ultrasound-

sonographers completed the questionnaire. There was an ergonomic effect on gender for microbiology technicians

(p-value was 0.043). Moreover, the ultrasound-sonographers had a signi cant association between gender and pain

595

Medical

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 11(4): 595-602 (2018)

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

Corresponding Authors: shahryf@hotmail.com

Received 1

st

Aug, 2018

Accepted after revision 23

rd

Nov, 2018

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC / Clarivate Analytics USA

Mono of Clarivate Analytics and Crossref Indexed

Journal Mono of CR

NAAS Journal Score 2018: 4.31 SJIF 2017: 4.196

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, Bhopal India

2018. All rights reserved.

Online Contents Available at:

http//www.bbrc.in/

DOI: 10.21786/bbrc/11.4/9

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

596 ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

related to work (p value < 0.001). Awareness however, in microbiology technicians, was found to be 83% who knew

the meaning of ergonomics and 85% in ultrasound sonographers. In conclusion, there was a signi cant effect of

ergonomic on sonographers and microbiology technician. The study showed a good level of knowledge and aware-

ness about ergonomics, however, still there is a quiet high percentage of them who did not receive health education

on ergonomics and also a high percentage who aren’t implementing ergonomics. There is a need for educational and

implementation empowerment programs in this regard.

KEY WORDS: ERGONOMIC, ULTRASOUND, MICROBIOLOGY, OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY, MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

INTRODUCTION

‘Ergonomics’ is composed of two words which are ‘ergo’

a Greek word meaning work, and ‘nomics’ which means

study, Tayya et al. (1997) Pao et al. (2001) have de ned

ergonomics as a branch of science which analyses the

optimal relationship between workers and their environ-

ment. It is also described as a system that the work-

ers interact with the work environment, the tasks and

the workplace, (Brooks 1998). Ergonomics signi cantly

developed during World War II, and now includes design,

medicine, and computer science, (Goyal et al., 2009) as it

includes a variety of conditions that can affect workers

in different aspects such as health and comfort. Besides,

it also has factors that are contributing to the health

such as lighting, tools design, chair design, heavy lift-

ing and repetitive motion and others. These factors can

cause injuries and problems related to muscles, tendons

or nerves which can lead to musculoskeletal disorders

(MSDs), (Jaffar et al., 2011, Mcatamney et al., 2017).

Musculoskeletal disorders MSDs are injuries and dis-

orders that affect the nerves and soft tissues which are

muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints. According to Yelin

et al. (1999) the majority of the old workers were disabled

due to MSDs, which were also observed among female

care givers. Therefore, poor ergonomics have an impact

on the worker’s health and can lead to occupational health

injuries. According to Lee, ergonomics is promoting com-

patibility between humans and systems, (Lee 2017).

Considering the workers’ limitations and capabilities

by tting environments, and tasks to improve the pro-

ductivity and safe work performance reduce costs due

to work injuries. There are many types of jobs which

require moderate to heavy physical work such as health

care workers, engineers, food industry workers, manual

workers, and of ce workers and other service staff.

Inappropriate workplace design, tools and equipment

machine lead to fatigue, frustrate, and hurt the workers.

The most extreme risk factors which affect the workers

on the worksite are the uncomfortable static position,

repetitive motion, vibration, heavy lifting, temperature,

and lighting. Many studies have shown that work inju-

ries and pain caused by risk factors of ergonomics result

from frequent bending, twisting, heavy physical activi-

ties, heavy (manual) lifting and whole-body vibration,

(Estryn-Behar et al. 1990, Kuiper et al. 1999 and Lee

2017).

One of the most arduous professionals that require over-

load on the body, forced position, and long working hours

are working in health care. Doctors, Nurses, Radiologists,

Dentists and other groups in the healthcare professions

show a high incidence of work-related injuries and pain

result from a singular (acute) event to gradual events of

repetitive movement which lead to handling patients and

equipment. Several studies are showing high-risk factors

of ergonomics among healthcare workers. The primary

factors which can increase musculoskeletal injuries and

induce pain among health care workers are load (weight

and size of materials, the force needed to push or pull, a

position of handholds, and a shape of handles) and posture

(disadvantageous positions of the arms and legs, forward

bend and twist of the trunk) and environment (inappro-

priate oor conditions, insuf cient equipment, inadequate

lighting and thermal conditions, and time pressure). Ergo-

nomics have a high impact on the worker, and poor ergo-

nomics may lead to MSDs. The job of health care workers

and other professionals demand a tremendous physical

load to improve the productivity of healthcare and hence

adequate quality; the ergonomics prevents the risk fac-

tors and work-related injuries. Proper of ce ergonomics

contribute to increase workers’ effectiveness and reduce

musculoskeletal injuries that associated with of ce work-

ing. Recent studies pointed out that poor ergonomics of

the above areas lead to MSDs and pain on the workers.

Work in radiology area demands physical tasks such

as patient’s transfer and using imaging equipment and

computer-related task. Accordingly, improved ergonom-

ics of the radiology department will contribute to reduce

the risk of work-related injuries and provide the safety

when dealing with patients, (Siegal et al. 2010, Ruess

et al. 2003). In regards to laboratory work, it needs a

prolonged standing position. Because of that laboratory

healthcare workers are more exposed to MSDs and poor

ergonomics can lead to pain in the different area of the

body, (Agrawal et al. 2015).

There is a paucity of data on the ergonomics of places

involving patient care, sites of diagnosis of diseases such

as radiology and laboratories. Hence the present study

was planned and proposed so that the evidence created

from the study will give light to the ergonomic effects

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS 597

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Male Female

Microbiology-technicians (N) 4 14

Percentage (%) 22.2 77.8

Years of experience (mean) 2.67

Ultrasound-sonographers ( N) 4 23

Percentage (%) 14.8 85.2

Years of experience (mean) 10.22

on workers of selected healthcare areas. This study was

aimed to assess the ergonomic effect on workers of ultra-

sound and microbiology technicians of areas in KAMC-

Riyadh, and to identify the ergonomic factors and the

presence of work-related injuries, it also compared the

ergonomical awareness of the workers.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional quantitative study conducted at

National Guard Hospital (NGH), in Riyadh over 6-months

period from Aug to Nov 2017. The study was approved

by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah Inter-

national Medical Research Center (KAIMRC). The study

included technicians from two different areas. The rst

area is radiology; the inclusion criteria of radiologist

workers were a technician working at Ultrasound areas

(which include sonographers works in general Ultra-

sound, Mammogram areas, Echo areas, and OB-GYN

areas), including all ages and both genders. The exclusion

criteria were the other areas such as Magnetic Resonance

Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT). The other

area is a laboratory, the inclusion criteria were microbiol-

ogy technician, including all ages and both gender. The

exclusion criteria were workers in other areas of labora-

tory such as hematology. With a population of 60 techni-

cians, 50% margin of error of 95% of con dence level,

the required sample size was calculated as 53. Selection

of samples based on the departments. The sample size for

workers in the radiology department is 18, and the sample

size for workers in the laboratory is 27.

A self-developed questionnaire was used to collect the

data from the workers. The questionnaires constructed of

yes or no questions (microbiology department 37 ques-

tions and radiography department 30 questions) and

demographic data was adapted for our study to determine

the most common physical problems that workers experi-

ence in their workstation, the effect of ergonomics, and

the awareness of ergonomic among the healthcare work-

ers. The procedure of the study done after identi cation of

the subjects and the consent form was obtained from the

participants before enrolling in the study. The question-

naires were distributed randomly among laboratory and

radiology workers. All the data collected were analyzed

by SPSS version 21 software, and descriptive statistics

were used to summarize the data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

STUDY POPULATION

We identi ed 45 microbiology-technicians and Ultra-

sound-sonographers. The Microbiology-technicians

were 18 participants (40.0%) completed the question-

naire, with a mean age of 26 years (SD = 3.97). The

Ultrasound-sonographers were 27 participants (60.0%)

completed the questionnaire, with a mean age of 35

years (SD = 7.17) (see Table 1 for further information).

Ergonomic Effects on Health Care Workers

Ergonomic Effects on Microbiology-technicians

A signi cant association between gender and pain

related to work (p-value was 0.043). We found that 50%

of male and 92% of female have pain or discomfort

related to work. We reveals that the most common pain

positions among both genders were lower back (16%),

followed by Feet heel (14%), Neck and shoulder blade

(12%), Shoulders and headache (10%), dry eyes (9%),

eye strain (7%), depression and wrist (5%). We found

that (60%) of both genders reported that the pain started

at the end time of the workday (p-value was 0.017).

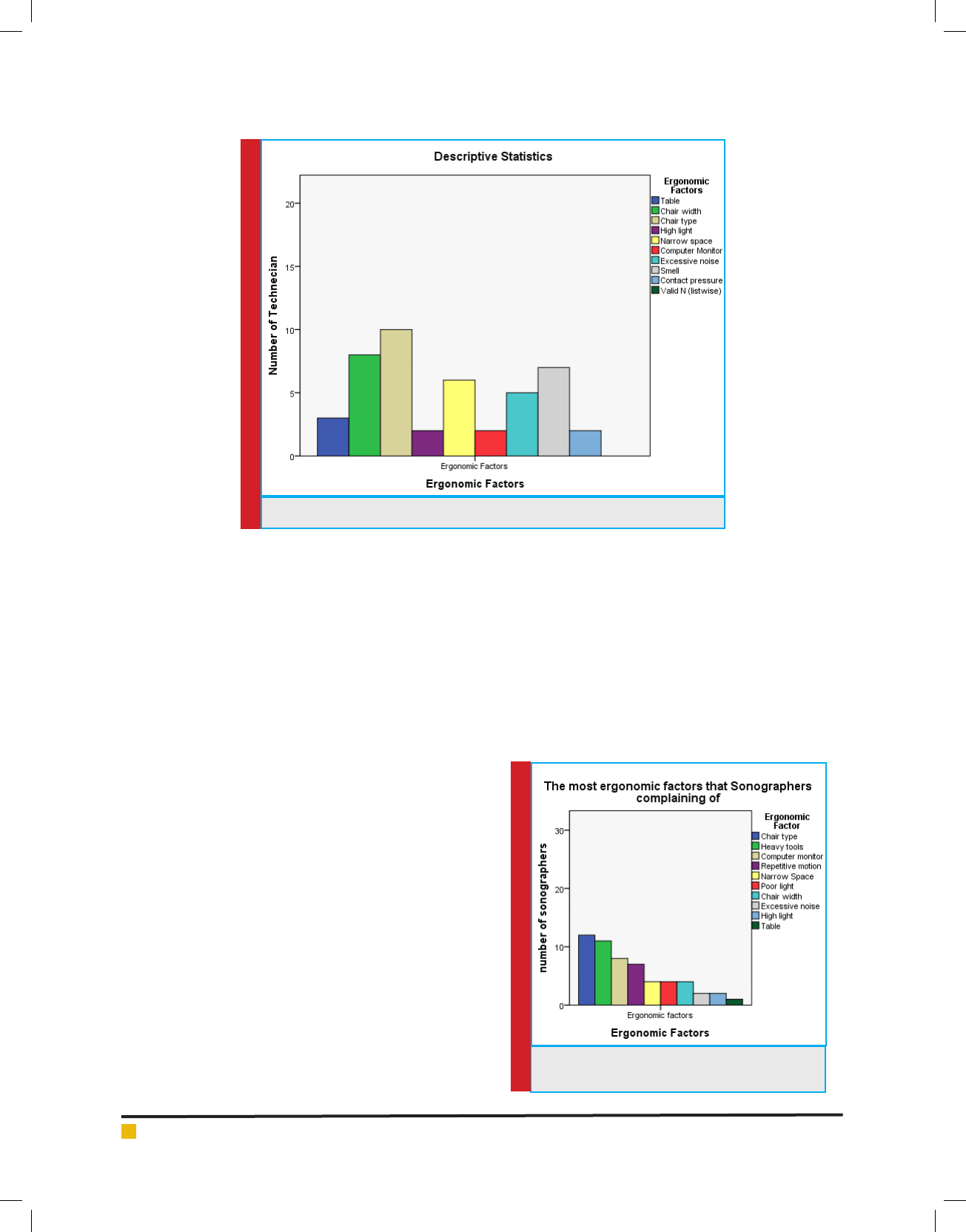

Table 2 & gure 1 shows that most common activities

of daily living that affected by work-related pain were

social activities and sleep (33%), family demands (27%),

work productivity and health maintenance (16%). The

results show that, the most common factor the partici-

pants were complaining of was chair type (55%), fol-

lowed by chair width (44%), smell (38%), narrow space

(33%), excessive noise (27%), table (16%), high light and

computer monitor and contact pressure (11%). Regard-

ing the techniques and changes that technician used to

decrease the pain related to work, we found that most

of them applying stretching exercise (50%), massage

(44%), and the rest either take painkillers, smoking or

Table 2. Activities that affected by work injuries on

microbiology technicians

n Total Pearson

Chi-Square

p-value

Social activity 6 18 .643ª 0.432

Sleep 6 18 .643ª 0.423

Family demands 5 18 .020ª 0.888

Work productivity 3 18 .257ª 0.612

Health maintenance 3 18 4.114ª 0.043

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

598 ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

FIGURE 1. The most ergonomic factors that microbiology complaining

nothing. None of them try to visit Occupational therapy

clinics to get help and education about some techniques

and changes that help to decrease and eliminate pain

and injuries related to work. As a solution to reduce and

eliminate pain related to work, we found that most of

technician suggest to add regular short breaks (50%),

decrease the work hours (33%), increase the number of

technicians (33%), add regular stretching exercise (33%),

made changes in the workplace (22%), and training and

education about proper ergonomics (22%).

Ergonomic Effects on Ultrasound-sonographers.

A signi cant association between gender and pain

related to work (p-value < 0.001). We found that 75% of

the male and 86% of the female have pain or discom-

fort related to work. Fig 2 reveals that the most com-

mon pain positions among both genders were shoulders

(17%), followed by upper back (12%), Neck (11%), shoul-

der blade and lower back (10%), foot heel and dry eyes

(8%), ngers (7%), wrist (6%), and elbow-forearm (5%).

We found that (77%) of both genders reported that the

pain started at the end time of the workday. Table 3

shows that most common activities of daily living that

affected by work-related pain were family demands

(48%), work productivity (40%), social activities (37%),

sleep (33%), and health maintenance (18%). The results

show that, the most common factor the participants were

complaining of was chair type (44%), followed by heavy

tools (40%), computer monitor (29%), repetitive motion

(25%), narrow space and poor light and chair width

(14%), excessive noise and high light (7%), and table

(3%) (Figure 2). Regarding the techniques and changes

that sonographers used to decrease the pain related to

work, we found that most of them doing massage (62%),

stretching exercise (55%), ask for sick leave and go to

physician (14%), and go to physiotherapy clinics (7%).

None of them try to visit Occupational therapy clinics

to get help and education about some techniques and

changes that help to decrease and eliminate pain and

injuries related to work. As a solution to minimize and

eliminate pain related to work, we found that most of

technicians suggest having training and education

FIGURE 2. The most ergonomic factors that

sonographers complaining

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS 599

Table 3. Activities that affected by work injuries on

sonographers

N Total Pearson

Chi-Square

p-value

Family demands 13 27 .006ª 0.088

Work productivity 11 27 .167ª 0.683

Social Activities 10 27 2.902ª 0.936

Sleep 9 27 .147ª 0.720

Health maintenance 5 27 1.067ª 0.302

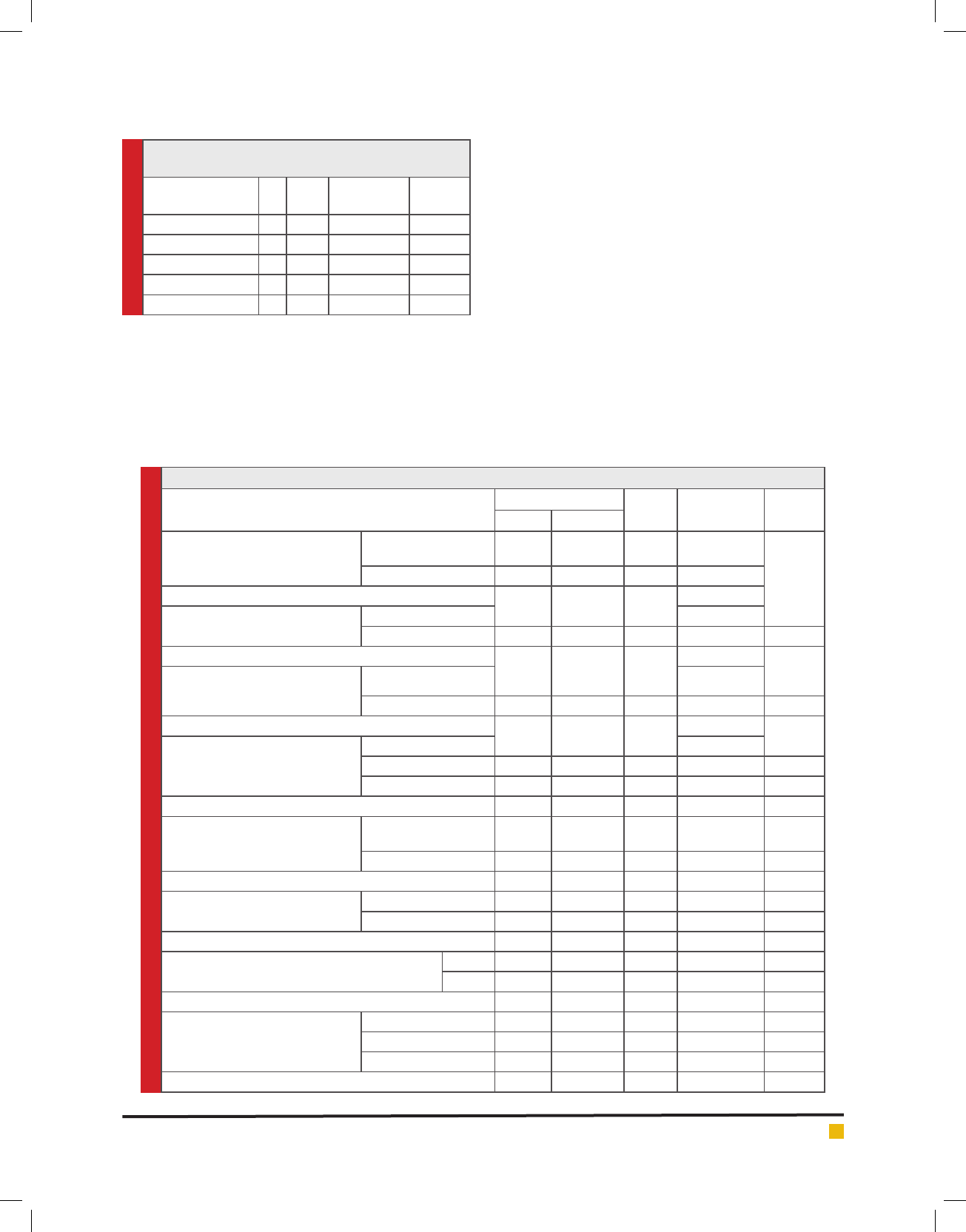

Table 4. Awareness of Ergonomics

Gender Total Pearson Chi-

Square

p-value

Male Female

Microbiology-technicians

Know the meaning of ergonomics No 1 2 3 .257ª .612

Yes 3 12 15

Total 4

1

14

1

18

2

Poor ergonomics lead to health risk No

Yes 3 13 16 1.004ª .316

Total 4

1

14

8

18

9

Educated about proper posture No

Yes 3 6 9 1.286ª .257

Total 4

2

14

5

18

7

Implement proper body mechanics No

Yes 1 7 8

not applicable 1 2 3 .815ª .665

Total 4 14 18

Ultrasound-sonographers

Know the meaning of ergonomics No 1 3 4

Yes 3 20 23 .386ª .534

Total 4 23 27

Poor ergonomic lead to health risk No 1 4 5

Yes 3 19 22 .131ª .718

Total 4 23 27

Education about proper posture

Yes

No 2 7 9

2 16 18 .587ª .444

Total 4 23 27

Implement proper body mechanics No 1 5 6

Yes 1 14 15

Not applicable 2 4 6 2.436ª .296

Total 4 23 27

about proper ergonomics (62%), increasing the number

of sonographers and adding regular stretching exercise

(59%), adding regular short breaks (40%), decreasing the

work hours (25%), and made changes in the workplace

(18%).

3.3. Awareness

Regarding the awareness in Microbiology technician, we

found that 83% who know the meaning of ergonomics,

88% who think poor ergonomics lead to health risk, 50%

who get an education about proper posture and body

mechanics, and 44% who implemented the appropriate

posture and body mechanics. In Ultrasound sonogra-

phers, we found that 85% who know the meaning of

ergonomics, 81% who think poor ergonomics lead to

health risk, 66% who get an education about proper pos-

ture and body mechanics, and 55% who implemented

the proper posture and body mechanics. (see Table 4 for

further information).

The current study ndings showed that there are

signi cantly higher feelings of pain and discomfort in

female compared to male participants. This nding is

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

600 ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

by what had been previously reported in the literature,

where the current human results concerning sex differ-

ences in experimental pain indicate greater pain sen-

sitivity among females compared with males for most

pain modalities. Additionally, many previous studies

con rmed differences between genders and documented

that women are more likely to experience musculoskel-

etal pain, (Cook et al., 2000, Ranasinghe et al., 2011).

In line with the study of Kaliniene et al. (2016), the

current study showed that low back pain was the high-

est prevalent type of pain among the studied cohort.

Additionally, a similar study conducted in Nigeria, and

the authors found a high preponderance of upper and

lower back pain Kayoed et al. (2013). The predominant

involvement of the back, as observed in the current

study, also is in agreement with reports of studies carried

out in Roma, British Columbia, and United States, (Pike,

et al. 1997, Mirk,et al 1999). Additionally, shoulder pain

was among the most reported pain positions in the cur-

rent study and in that of Kaliniene et al. (2016).

The current study nding highlighted the point that

the lack of attention to ergonomics could lead to dam-

age to the healthcare workers mainly in the form of mus-

culoskeletal pain, stress injuries and eye strain which

can lead to increase the workers’ fatigue and decrease

their productivity, and this is in accordance with what

has been reported in the literature, (Hills et al., 2012). It

has been demonstrated that MSDs are highly relevant

in the context of work and that the current economic

and social implications of these conditions are sizeable

and often underestimated. There are some types of jobs

and speci c sectors including home care and nursing,

represent a heightened risk of developing or aggravating

MSDs. The converse of work environments that aggra-

vate MSDs is that work context can also contribute to

improvements in MSD outcomes mainly through ergo-

nomic design and job duty adjustment, (Summers, et al.,

2015).

In sonography, surveys done among American and

Canadian sonographers in 1997 showed that the inci-

dence of MSDs was 84%; however, this incidence had

increased to 90% (Evans et al., 2009). An ergonomic

workstation in sonography according to Baker and

workers should include an ergonomic task chair, the

chair should be easy to operate and be adjustable from a

settled position, has a different lift, vinyl upholstery that

is antimicrobial, a foot ring, special casters, and detailed

instructions on its use for different types of studies,

however, then they reported that the ergonomic features

of the examination room equipment are only as good as

the workers willingness to use them, (Baker et al., 2015)

.

The effectiveness key of these features is changing

the worker work postures so that they maintain neutral

postures for the majority of each examination. Comfort-

able work postures can make any ultrasound worksta-

tion ergonomic, increase worker comfort, reduce injury

risk, and impact the quality of patient care Baker et al.

(2015). In the Nigerian study published in 2013, the most

signi cant proportion of the participants reported that

the use of chairs of low height and scanning chair both

precipitated and aggravated their symptoms and feeling

with pain, and they recommended the use of chairs and

scanning tables of ideal heights that can decrease risks

to musculoskeletal disorders associated with Ultrasonog-

raphy, (Kayoed et al., 2013). The current study partici-

pants reported that their primary complaint and width.

For ultrasound practitioners, to empower safe working

practices the room should was from the chairs type be of

an adequate size, (Tayyari et al., 1997) with lighting that

does not cause glare on the monitor and heating that is

suitable for the working conditions, (Baker et al., 2015

and Harrison et al., 2015).

This is in line with what the current respondents

reported that narrow space is one of the common fac-

tors of their complaint. Massage and stretching exercises

were the most common techniques and changes that

sonographers in the current study used to decrease the

pain related to work. Harrison and Harris (2015) in their

review concluded that there are many factors involved

in the prevention or the reduction of work-related MSDs

for ultrasound practitioners. These factors include ergo-

nomic issues, management of workload, psychosocial

factors, physical factors and general tness levels. Sun-

ley et al. (2006) highlighted that ergonomics education

for staff is essential to ensure that they are aware of best

practice guidelines, ways of risk reduction to themselves

and others and how to report and monitored pain and

injury to ensure a long and healthy career, (Sunley et al.,

2006). In the current study, results indicated that there is

a shortage in ergonomics education; additionally, a high

percentage of the respondents show their wish to receive

education and training about ergonomics.

As per the results of several studies, the effects of

occupational MSD interventions have been particu-

larly strong when using a multi-branched intervention

approach, combining physical exercise with another

component, like worksite ergonomic changes, (Dawson

et al., 2007, Holtermann et al., 2010). Unfortunately,

none of the participants in the current study tried to

visit occupational therapy clinics to get help and educa-

tion about some techniques and changes that help to

decrease and eliminate pain and injuries related to work.

For healthcare workers, the previous study has shown

that social, environmental factors such as work demands

and social support are related to report MSDs, (Sorensen

et al., 2011), which is almost the same with our study

ndings. Taken together with the evidence from previ-

ous interventions, these ndings support intervention

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS 601

strategies that incorporate targeted changes to the phys-

ical and social work environment along with worker

education.

For tackling MSDs at work, several preventive strate-

gies can be taken. These prevention strategies primar-

ily include risk assessment, and technical/ergonomic,

organizational and person-oriented intervention. The

secondary prevention strategy involves the identi ca-

tion and health monitoring of workers at risks, while the

tertiary prevention strategy comprises a return to work

actions, Mirk et al., 1999, EU-OSHA 2008. Suggestions

of the current study respondents regarding a solution to

decrease and eliminate pain related to work were within

the context of those prevention strategies with adding

regular short breaks being the highest scored sugges-

tion. In line with this nding, a previous study identi ed

that lack of rest breaks and use of facilities that are not

ergonomic were the main contributing factors to work-

related MSDs Kayoed et al. (2013).

Some studies on sonographers have also linked reg-

ular breaks and reduced workload to reduced muscu-

loskeletal symptoms, Schoenfeld et al. (1999). On the

other hand, the work of Schoenfeld et al. (2013) did not

nd reduced scanning frequency to be associated with

reduced symptoms among sonographers. Microbiology

technicians participated in the current study showed

a right awareness level with the term “ergonomics,” a

result which is better compared to the Nigerian research

about awareness and knowledge of ergonomics among

medical laboratory scientists, in which awareness of

ergonomics and knowledge of gains of its right applica-

tion was reduced, Oladeinde et al. (2015).

Additionally, it is better than what recorded elsewhere

among computer users and manufacturing workers, (Loo

et al., 2012, Shantakumari et al., 2012). The strengths

of this study include that the data about ergonomics is

scarce in Saudi Arabia, and to the best of our knowl-

edge, this is the rst study in Saudi Arabia that assesses

the ergonomic effects on workers of selected healthcare

areas. Second, healthcare workers especially those who

participate in interventional procedures such as labo-

ratory and radiology are well known and more prone

to have musculoskeletal pain. Third, the data come

from one of the biggest national hospitals in Riyadh.

This study has some limitations including mainly the

small sample size in microbiology technicians, and the

participants were only from one healthcare institution.

The results of this study may be further enhanced in the

future by increasing the sample size.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there is a signi cant effect of ergonomic

on sonographers and the laboratory technicians. The

study showed a good level of knowledge and awareness

about ergonomics; however, still, there is a quite high

percentage of them who did not receive health education

on ergonomics and also a high percentage who aren’t

implementing it. There is a need for educational and

implementation empowerment programs in this regard.

REFERENCES

Agrawal Parul R, Maiya Arun G, Kamath V, Kamath A. (2015)

Musculoskeletal Disorders among Medical Laboratory Profes-

sionals-A Prevalence Study. Journal of Exercise Science and

Physiotherapy. 10(2):77.

Baker JP, Cof n CT. (2013) The importance of an ergonomic

workstation to practicing sonographers. J Ultrasound Med.

Aug; 32(8):1363–75.

Bergische Universität Wuppertal, pp. 72 Available at: www.

dguv.de/content/prevention/campaigns/msd/review/ap_4_e.pdf

Brooks A. (1998) Ergonomic approaches to of ce layout and

space planning. Journal of Facilities.; 16(3/4):73-78.

Cook C, Limerick BR, Chang S. (2000) The prevalence of neck

and upper extremity musculoskeletal symptoms in computer

mouse users. Int J Ind Ergon.; 26:347–56.

Dawson AP, McLennan SN, Schiller SD, Jull GA, Hodges PW,

Stewart S. (2007) Interventions to prevent back pain and back

injury in nurses: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. Oct;

64(10):642–50.

Estryn-Behar M, Kaminski M, Peigne E, Maillard M, Pelletier

A, Berthier C et al. (1990) Strenuous working conditions and

musculo-skeletal disorders among female hospital workers.

International Archives of Occupational and Environmental

Health; 62(1):47-57.

EU-OSHA - European Agency for Safety and Health and

Work, (2008) Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: pre-

vention report, Publications Of ce of the European Union,

Luxembourg,pp.106.Availableathttps://osha.europa.eu/en/

publications/reports/en_TE8107132ENC.pdf/view.

Goyal N, Jain N, Rachapalli V. (2009) Ergonomics in radiology.

Clinical Radiology.; 64(2):119-126.

Harrison G, Harris A. (2015) Work-related musculoskeletal dis-

orders in ultrasound: Can you reduce risk? Ultrasound. Nov;

23(4):224–30.

Hills DJ, Joyce CM, Humphreys JS. (2012) A national study of

workplace aggression in Australian clinical medical practice.

The Medical Journal of Australia. Sep 17; 197(6):336–40.

Holtermann A, Mortensen OS, Burr H, Søgaard K, Gyntelberg

F, Suadicani P. (2010) Physical work demands, hypertension

status, and risk of ischemic heart disease and all-cause mortal-

ity in the Copenhagen.

Jaffar N. (2011) A Literature Review of Ergonomics Risk Fac-

tors in Construction Industry. Procedia Engineering.; 20:89-97.

Kaliniene G, Ustinaviciene R, Skemiene L, Vaiciulis V, Vasilav-

icius P.(2016) Associations between musculoskeletal pain and

work-related factors among public service sector computer

Fayz Al Shahry et al.

602 ERGONOMIC EFFECTS ON WORKERS OF SELECTED HEALTHCARE AREAS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

workers in Kaunas County, Lithuania. BMC Musculoskelet Dis-

ord. 07; 17(1):420.

Kayoed I. Oke and A. A. Adeyekun. (2013) Patterns of Work-

related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Sonographers in

selected Health Facilities in Nigeria. Journal of Applied Medi-

cal Sciences, vol. 2, no. 4, 67-76

Kevin Evans, Shawn Roll, Joan Baker .(2009) Work-Related

Musculoskeletal Disorders (WRMSD) Among Registered Diag-

nostic Medical Sonographers and Vascular Technologists: A

Representative Sample. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonog-

raphy. Nov 1; 25(6):287–99.

Kuiper J, Burdorf A, Verbeek J, Frings-Dresen M, van der Beek

A, Viikari-Juntura E. (1999) Epidemiologic evidence on man-

ual materials handling as a risk factor for back disorders:a sys-

tematic review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonom-

ics.; 24(4):389-404.

Lee K. (2017) Ergonomics in total quality management: How

can we sell ergonomics to management? Journal of Ergonom-

ics.; 48:5,547-558.

Loo HS, Richardson S, Alam S. (2012) Ergonomics issues in

Malaysia. J Soc Sci. 8:61–5.

Magnavita N, Bevilacqua L, Mirk P, Fileni A, Castellino N.

Work-related musculoskeletal complaints in sonologists. J

Occup Environ Med. 1999 Nov; 41(11):981–8.

Mcatamney L, Corlett E. (2007) Ergonomic workplace assess-

ment in a health care context. Institute for Occupational Ergo-

nomics, University of Nottingham.; 35(9):965-978.

Michaelis, M., IPP-aMSE (2009) Identi cation and prioriti-

sation of relevant prevention issues for work-related mus-

culoskeletal disorders (MSD) - Work package 4 - Prevention

approaches: evidence-based effects and prioritised national

strategies in other countries,

Mirk P, Magnavita N, Masini L, Bazzocchi M, Fileni A. (1999)

Frequency of musculoskeletal symptoms in diagnostic medi-

cal sonographers. Results of a pilot survey]. Radiol Med. Oct;

98(4):236–41.

Mirk, P L. Magnativa, M. Bazzocihi and A. Fileni. (1999) Fre-

quency of musculoskeletal symptoms in diagnostic medical

sonographers. Review of a pilot survey. Radiol. Med., 98(4),

236-41

Oladeinde BH, Ekejindu IM, Omoregie R, Aguh OD. (2015)

Awareness and Knowledge of Ergonomics among Medical

Laboratory Scientists in Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. Dec;

5(6):423–7.

Pao T, Kleiner B. (2001) New developments concerning

the occupational safety and health act. Managerial Law;

43(1/2):138-146.

Pike, J. Russo, Berkowitz, J.P. Baker and V.A. Lessoway. (1997)

The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and related work

and personal factors among diagnostic medical sonographers.

J Diag Medical Sonography, 13(5), 219-227.

Ranasinghe P, Perera YS, Lamabadusuriya DA, Kulatunga S,

Jayawardana N, Rajapakse S, et al. (2011) Work related com-

plaints of neck, shoulder and arm among computer of ce

workers: a cross-sectional evaluation of prevalence and risk

factors in a developing country. Environmental Health.;

10:70.

Ruess L, O’Connor S, Cho K, Hussain F, Houuard W, Slaughti

R et al. (2003) Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Cubital Tunnel

Syndrome: Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Four

Symptomatic Radiologists. American Journal of Roentgenol-

ogy.; 181:37-42.

Schoenfeld A, Goverman J, Weiss DM, Meizner I. (1999) Trans-

ducer user syndrome: an occupational hazard of the ultra-

sonographer. Eur J Ultrasound. Sep; 10(1):41–5.

Shantakumari N, Eldeeb RA, Sreedharan J, Gopal K. (2012)

Awareness and practice of computer ergonomics among uni-

versity students. Int J Med Health Sci.; 1:16–20.

Siegal D, Levine D, Siewert B, Lagrotteria D, Affeln D, Denner-

lein J et al. (2010) Repetitive Stress Symptoms Among Radiol-

ogy Technologists: Prevalence and Major Causative Factors.;

7:956-960.

Sorensen G, Stoddard AM, Stoffel S, Buxton O, Sembajwe G,

Hashimoto D. (2011) The role of the work context in multiple

wellness outcomes for hospital patient care workers. J Occup

Environ Med. Aug; 53(8):899–910.

Summers, K., Jinnet, K. & Bevan, S. (2015). Musculoskeletal

disorders, workforce health and productivity in the United

States. The Work Foundation. London, pp 40.

Sunley K. (2006) Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal

Disorders In Sonography. London: Society of Radiographers,

Tayyari F, Smith J .Occupational Ergonomics: principle and

application. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. P. 4-214.

Yelin E, Trupin L, Sebesta D. (1999) Transitions in employment,

morbidity, and disability among persons ages 51–61 with mus-

culoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal conditions in the US,

1992–1994. Arthritis & Rheumatism.; 42(4):769.