Biotechnological

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 11(2): 263-269 (2018)

Nutritional assessment of different date fruits (

Phoenix

dactylifera L.

) varieties cultivated in Hail province,

Saudi Arabia

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi

1

, Amir Mahgoub Awadelkarem

2

, A.B.M. Sharif Hossain

1

, Nasir A

Ibrahim

1,3

, Mohammad Fawzi

1

and Syed Amir Ashraf

2

*

1

Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Hail, P.O.Box 659, Hail 81421, Saudi Arabia

2

Department of Clinical Nutrition, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia

3

Department of Biochemistry and Physiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Albutana, Sudan

ABSTRACT

Date fruits are an imperative crop, especially cultivated in the hot-arid regions of the world having extraordinary

nutritional and therapeutic value. In this study, we performed nutritional pro ling and mineral analysis of different

varieties of date fruits cultivated in north-western region of Saudi Arabia. Among the sample tested, we found that

moisture contents was highest in Helwah Hail (23.83 ± 0.49%) and Berhi (23.20 ± 0.10%). Moreover, ash and protein

content was found to be more in Ajwah (2.50 ± 0.53%) and Hamra (4.34 ± 0.06%) respectively. Similarly, total bre

percentage of the tested sample varied from 4.35 ± 0.05% to 5.13 ± 0.12% and monosaccharaides was found highest

in Helwah Hail and Deglet Shewaish. However, mineral analysis showed that Ajwah date fruits, Asilah, Nabtat Saif

and Barni had high amount of calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium respectively. The present nding helps in

understanding the nutritional status and signi cance of different date varieties cultivated in north-western region of

Saudi Arabia (Hail Region). However, lesser known varieties can be improved through better horticulture practices as

a valuable product. Further, this study reveals that, the consumption of these date fruits would have several nutri-

tional health effects.

KEY WORDS: NUTRIENT ANALYSIS, PROXIMATE ANALYSIS, DATE FRUITS, HAIL PROVINCE, MINERALS

263

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: s.amir@uoh.edu.sa

Received 10

th

Jan, 2018

Accepted after revision 19

th

March, 2018

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC / Clarivate Analytics USA and

Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2018: 4.31 SJIF 2017: 4.196

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, Bhopal India

2018. All rights reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

DOI: 10.21786/bbrc/11.1/11

264 NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

INTRODUCTION

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L., family Arecaceae)

is one of the oldest fruit trees on the earth and is closely

associated with the life of the human beings in the Mid-

dle East countries including the Kingdom of Saudi Ara-

bia (Al-Abdoulhadi et al., 2011). Saudi Arabia is con-

sidered as the mother country of date palm trees and is

second largest producer of date fruits in the world, with

more than 300 types of dates, each with its own taste

and texture, but only around 50–60 cultivars are used

commercially. In 2013, date production in Saudi Arabia

reached 1,065, 032 tons, from 3·7 million trees (Assirey

2015; Allbed et al., 2017). However, few studies have

also showed that the Kingdom occupies the rst rank in

the world in terms of average per capita consumption

of dates per year, which reached 34.8 kg/year in 2003

(Al Shreed et al., 2012). Date fruits have great impor-

tance in human nutrition owing to their rich content

of essential nutrients which include carbohydrates sugar

ranging from 65% to 80% on dry weight basis mostly

of inverted form (glucose and fructose). Fresh varieties

have a higher content of inverted sugars, the semi dried

varieties contain equal amount of inverted sugars and

sucrose, while dried varieties contain higher sucrose,

(Aldjain et al., 2011; Hamad et al., 2015).

The nutritional value of dates is due to their high

sugar content as well as other important micro and

macro nutrients such as potassium (2.5 times more than

bananas), calcium, magnesium and iron. Other impor-

tant components are proteins, fat, vitamins, dietary ber,

fatty acids, polyphenols, antioxidant and amino acids,

(Chandrasekaran et al., 2013). In addition, date fruit

has been recommended in folk remedies for the treat-

ment of various diseases like diabetes, obesity, cancer

and heart diseases. Recently, it has been found that date

fruit might be of bene t in glycemic and lipid control of

diabetic patients and have also been identi ed as having

antioxidant and anti-mutagenic properties due to their

high levels of poly-phenolic compounds and vitamins

(Vayalil, 2012; Parvin et.al., 2015; Khalid et al., 2016).

In appreciation of its fruits, the date tree is referred to

as the sacred tree, the tree of life, and the bread of the

desert (Ghnimi et al., 2017).

With the increase in obesity and overweight among

Saudi nationals, especially young males and females due

to the life style and food habits, healthier balanced food

may be one of the solutions to this problem (Al-Haz-

zaa et al., 2012). Date fruits are a perfect food that can

provide the necessary minerals. Moreover dates can be

given to children instead of chocolates that contain var-

ious fats and additives that may subject them to health

problems. Dates have longer shelf life and can be stored

safely even at the high temperature of the Arabian Pen-

insula. Dates don’t require cooking or processing. All

of these advantages make dates one of the best food

stuff to be consumed (Taha et al., 2015). Considering the

nutritional facts and importance of date fruits studying

their nutritional quality is increasingly being recognized

as a worthy and important task. Our objective was to

evaluate the nutritional status and mineral composi-

tion of various varieties of Dates fruit cultivated in Hail

Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sample collection and preparation: Thirty two varieties

(Nabtat Saif, Khlas, Hamra, Ajwah, Shaishi, Barni, Sab-

bakah, Seghae, Roshodyyah, Nabtat Ali, Umm-Hamam,

Meskany, Rezazy, Asailah, Gasbah, Shaqraa, Menei ,

Sultanah, Wannanah, Umm Kebar, Dhahesyyah, Helwah,

Helwah Hail, Helwah Baqqa, Shebeby, Umm-Khashab,

Fankha, Berhi, Maktoomy, Sukkari, Deglet Shewaish

and Majhoolah) of date palm fruits were collected from

local markets and date fruits farms of Hail Province,

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Subsequently, samples were

washed with distilled water and the seeds were removed.

Later on, samples were grinded into uniform mixture

and stored in air tight containers until further analysis.

Determination of moisture and ash content: Two

grams sample were placed into the petri-dish and dried

in an oven at 105°C for three hours. The dried sample

was cooled in a desiccator for 30 min and weighed to

a constant weight. The percentage loss in weight was

expressed as percentage moisture content on dry weight

basis. However, determination of ash contents were per-

formed in triplicates and percentage residual weight was

expressed as ash content (Bashir et al., 2015).

Determination of total protein and fat percentage:

2g samples taken into thimble and placed into Soxhlet

apparatus for the determination of fat content using

petroleum ether (60 to 80°C) for 5 hours. Moreover,

determination of total proteins was performed by using

Kjeldahl method (AOAC, 2006).

Determination of total ber: From the pounded sample,

2.00 g were used in triplicates for estimating the crude

bre by acid and alkaline digestion methods using 20%

H

2

SO

4

and 20% NaOH solutions (AOAC, 2006).

Carbohydrate determination: Carbohydrate content

was calculated using the following formula: Available

carbohydrate (%) = 100 – [protein (%) + Moisture (%) +

Ash (%) + Fibre (%) + Crude Fat (%)](Bashir et al., 2015).

Determination of mineral contents: One gram of dried

sample and 50 ml of 20% Nitric acid (HNO3) were added

to Erlenmeyer ask. The mixture was heated to 70–85

0

C

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS 265

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

for 48 h. During heating period the volume of the ask

was maintained at the same level by intermittently add-

ing 20% nitric acid. After the completion of digestion

the content of Erlenmeyer ask was ltered using Nal-

gene lter (Thermo scienti c) unit. The ltrate was col-

lected in 100 ml volumetric ask and allowed to cool.

After cooling the volume was made up to 100 ml using

deionized water (Milli Q) and analyzed with ICP-MS. For

the sample preparation all the glassware was washed

with deionized water and rinsed three times with 20%

nitric acid (Ahmad et al., 2017).

Statistical analysis: All the experiments were carried

out in triplicates. The data were analyzed statistically

with SPSS-17 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago,

IL, USA). Mean was statistically compared by Duncan’s

multiple range test at P <0.05% level.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Date fruits have huge scope and potential for use as food

or as healthy food products because of an important

source of nutrition as well as economic signi cance.

Proximate analysis of date fruits are considered impor-

tant in grading, preservation, storage and processing of

dates. The average proximate composition and mineral

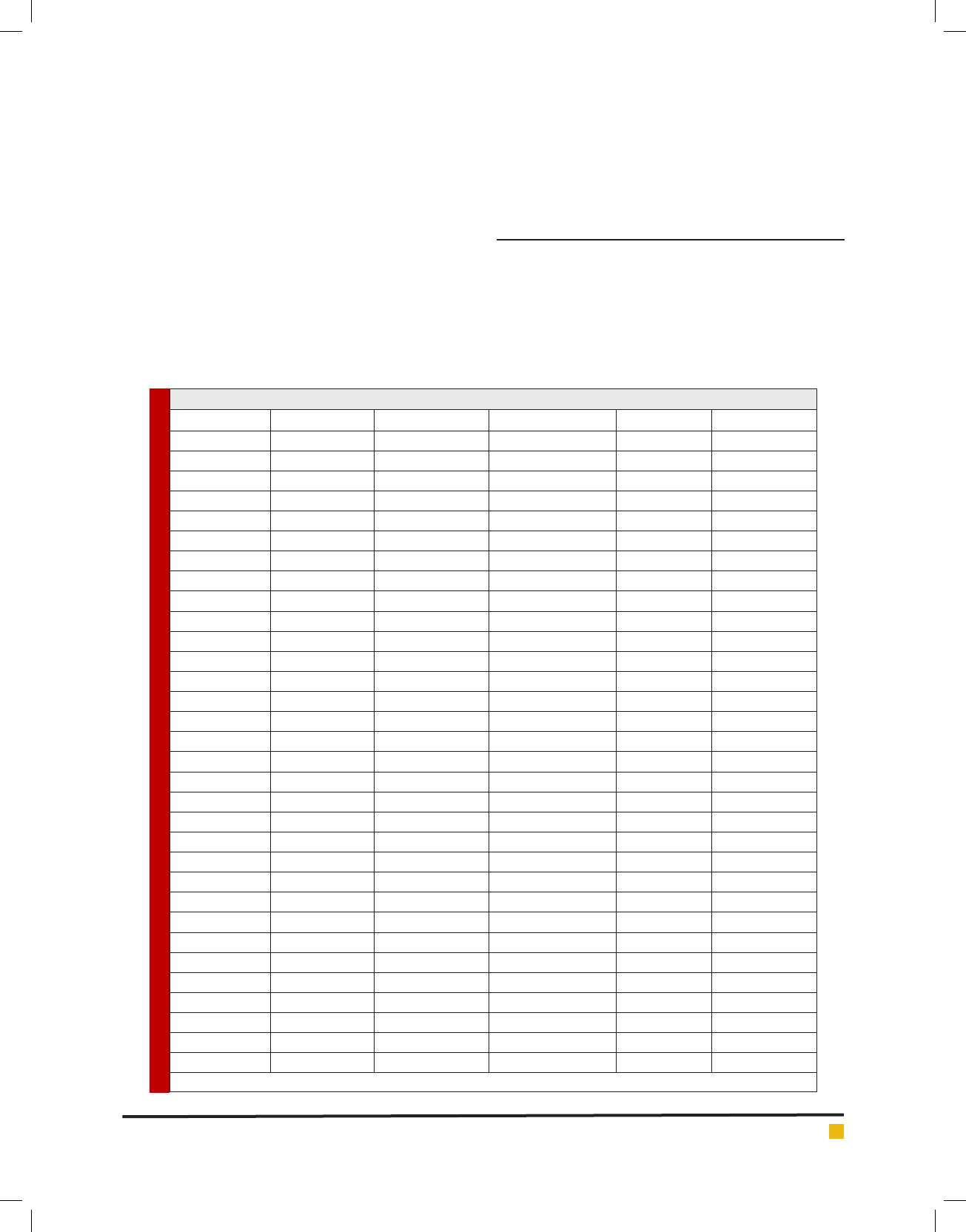

analysis of date fruits are presented in Tables 1,2 & 3.

Table 1. Proximate composition of date fruits

Sample Name Moisture (%) Ash (%) Fat (%) Protein (%) Total Fibre (%)

Nabtat Saif 18.03g ± 0.25 1.95 abcdef ± 0.19 0.43 abcd ± 0.025 2.70 def ± 0.10 4.52 bc ± 0.08

Khlas 18.73 gh ± 0.21 1.31 ab ± 0.09 0.45 abcdef ± 0.050 2.90 ghi ± 0.10 4.40 ab ± 0.10

Hamra 10.36 a ± 0.33 1.84 abcdef ± 0.55 0.55 ghij ± 0.500 4.34 q ± 0.06 4.35 a ± 0.05

Ajwah 14.56 d ± 0.59 2.50 ef ± 0.53 0.42 abc ± 0.015 3.15 kl ± 0.05 4.62 cd ± 0.08

Shaishi 15.97 ef ± 0.45 1.76 abcdef ± 0.05 0.52 efghij ± 0.085 3.29 lm ± 0.01 4.66 cde ± 0.04

Barni 11.23 ab ± 0.21 2.27 cdef ± 0.72 0.49bcdefghi ± 0.030 2.95 hij ± 0.05 4.39 ab ± 0.01

Sabbakah 14.87 de ± 0.35 2.51 f ± 0.34 0.42 abcd ± 0.040 3.25 klm± 0.05 4.65 cde ± 0.05

Seghae 12.43 c ± 0.11 2.14 bcdef ± 0.51 0.50 cdefghij ± 0.020 2.64 cde± 0.06 4.87 fghij ± 0.03

Roshodyyah 18.70 gh ± 0.30 2.15 bcdef ± 0.47 0.46 abcdef ± 0.060 2.29 a ± 0.04 4.95 hijk ± 0.05

Nabtat Ali 15.63 def ± 0.15 2.04 abcdef ± 0.46 0.48bcdefgh ± 0.020 2.60 cd ± 0.10 4.85 fghi ± 0.05

Umm-Hamam 18.50 gh ± 0.10 1.24 a ± 0.15 0.39 a ± 0.135 2.50 bc ± 0.10 4.95 hijk ± 0.05

Meskany 19.50 hi ± 0.40 1.54 abcd ± 0.41 0.58 j ± 0.080 3.39 mn ± 0.01 4.80 efgh ± 0.20

Rezazy 11.97 bc ± 0.86 2.47 ef ± 0.57 0.49 bcdefghi ± 0.010 2.88 fgh ± 0.01 4.88 ghij ± 0.02

Asailah 16.20 f ± 0.61 1.67 abcde ± 0.15 0.45 abcdef ± 0.050 2.34 ab ± 0.05 4.95 hijk ± 0.05

Gasbah 22.06 lmn ± 0.05 1.54 abcd ± 0.30 0.43 abcde ± 0.030 2.72 defg ± 0.11 4.69 cdef ± 0.21

Shaqraa 22.13 lmn ± 0.49 1.68 abcdef ± 0.27 0.47 abcdefg ± 0.030 2.75 defg ± 0.05 4.86 fghi ± 0.04

Menei 22.57 mn ± 0.21 1.48 abcd ± 0.57 0.49 bcdefghi ± 0.035 3.75 p ± 0.05 4.85 fghi ± 0.05

Sultanah 21.53 klm ± 0.95 1.43 abc ± 0.06 0.50 cdefghij ± 0.060 3.08 ijk ± 0.07 4.90 ghij ± 0.10

Wannanah 20.47 ijk ± 1.13 1.40 ab ± 0.10 0.47 abcdefg ± 0.030 3.53 no ± 0.12 4.90 ghij ± 0.10

Umm Kebar 22.83 no ± 1.98 1.56 abcd ± 0.37 0.41 ab ± 0.020 3.68 op ± 0.17 4.90 ghij ± 0.20

Dhahesyyah 18.89 gh ± 0.11 1.67 abcde ± 0.46 0.46 abcdef ± 0.010 3.58 op ± 0.18 4.80 efgh ± 0.00

Helwah 18.57 gh ± 0.32 2.31 def ± 0.40 0.49 bcdefghi ± 0.010 3.30 lm ± 0.10 4.72 defg ± 0.08

Helwah Hail 23.83 o ± 0.49 1.87 abcdef ± 0.65 0.56 hij ± 0.060 2.95 hij ± 0.05 4.80 efgh ± 0.20

Helwah Baqqa 21.07 jkl ± 1.53 1.69 abcdef ± 0.35 0.51 defghij ± 0.015 2.80 efgh ± 0.20 4.85 fghi ± 0.05

Shebeby 19.47 hi ± 0.15 1.59 abcd ± 0.42 0.46 abcdef ± 0.015 3.20 kl± 0.20 5.13 k ± 0.12

Umm-Khashab 21.53 klm ± 0.31 1.80 abcdef ± 0.26 0.57 ij ± 0.050 2.70 def ± 0.10 4.78 defgh ± 0..07

Fankha 18.10 g ± 0.71 1.83 abcdef ± 0.48 0.52 fghij ± 0.000 2.70 def ± 0.10 5.00 ijk ± 0.10

Berhi 23.20 no ± 0.10 1.50 abcd ± 0.00 0.45 abcdef ± 0.010 2.96 hij ± 0.06 4.93 hij ± 0.07

Maktoomy 15.17 def ± 0.55 1.59 abcd ± 0.17 0.39 a ± 0.010 3.15 kl ± 0.15 5.03 jik ± 0.02

Sukkari 20.13 ij ± 1.70 1.85 abcdef ± 0.83 0.42 abcd ± 0.010 2.75 defg ± 0.15 4.95 hijk ± 0.10

Deglet Shewaish 14.40 d ± 0.10 1.55 abcd ± 0.13 0.49 bcdefghi ± 0.010 2.65 cde± 0.05 5.05 ik ± 0.05

Majhoolah 15.03 def ± 0.40 1.58 abcd ± 0.58 0.46 abcdef ± 0.006 3.10 jk ± 0.10 4.95 hijk ± 0.05

Means bearing different superscript letters are signi cantly different at p < 0.05.

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

266 NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

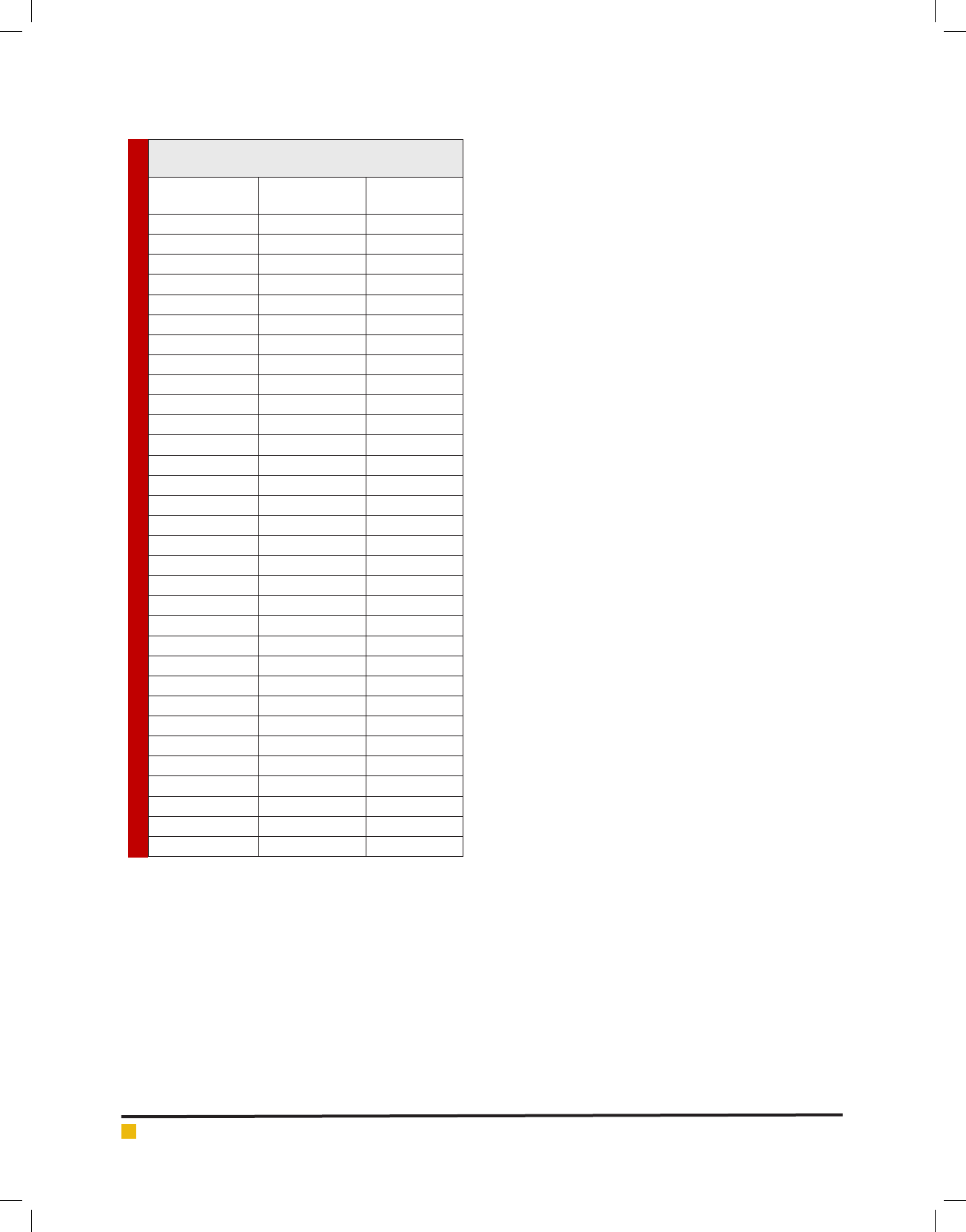

Table 2. Carbohydrate and monosaccharide sugar

analysis of date fruits

Sample Name Monosaccharide

(%)

Carbohydrate

(%)

Nabtat Saif 36.13 ef ± 0.66 72.23 i ± 0.35

Khlas 42.25 h ± 0.77 72.05 hi ± 0.05

Hamra 45.28 ij ± 0.82 78.69 m ± 0.34

Ajwah 45.29 ij ± 0.82 74.23 j ± 0.65

Shaishi 36.17 ef ± 0.66 73.83 j ± 0.37

Barni 36.13 ef ± 0.66 77.37 l ± 1.07

Sabbakah 48.39 k ± 0.88 74.23 j ± 0.09

Seghae 43.92 i ± 0.80 77.39 l ± 0.39

Roshodyyah 37.53 f ± 0.68 71.71 ghi ± 0.26

Nabtat Ali 43.92 i ± 0.80 74.12 j ± 0.42

Umm-Hamam 37.53 f ± 0.69 72.36 i ± 0.01

Meskany 37.53 f ± 0.69 70.12 ef ± 0.31

Rezazy 40.51 g ± 0.73 77.56 l ± 0.86

Asailah 43.92 i ± 0.80 74.11 j ± 0.51

Gasbah 39.97 g ± 0.73 68.24 cd ± 0.17

Shaqraa 34.89 de ± 0.63 68.07 bcd ± 0.61

Menei 56.68 n ± 1.03 66.94 ab ± .010

Sultanah 46.18 j ± 0.83 68.58 d ± 1.06

Wannanah 50.77 l ± 0.92 69.10 de ± 0.90

Umm Kebar 50.77 l ± 0.92 67.12 abc ± 2.25

Dhahesyyah 39.44 g ± 0.71 70.88 fgh ± 0.28

Helwah 27.36 a ± 0.49 70.54 fg ± 0.52

Helwah Hail 56.62 n ± 1.02 66.39 a ± 0.01

Helwah Baqqa 40.51 g ± 0.73 68.75 d ± 1.66

Shebeby 53.62 m ± 0.97 70.42 f ± 0.11

Umm-Khashab 32.65 c ± 0.59 68.72 d ± 0.41

Fankha 36.13 ef ± 0.66 72.19 i ± 0.11

Berhi 48.39 k ± 0.88 66.92 ab ± 0.06

Maktoomy 34.38 d ± 0.62 74.59 jk ± 0.51

Sukkari 43.92 i ± 0.81 69.94 ef ± 0.71

Deglet Shewaish 56.67 n ± 1.03 75.76 k ± 0.04

Majhoolah 30.66 b ± 0.56 75.09 jk ± 0.25

Moisture and ash contents: Our results showed that, the

moisture content in all the evaluated sample varies from

(10.36

a

± 0.33 - 23.20

no

± 0.10). Hamra date varieties

had lowest moisture percentage among the selected vari-

eties. Which indicates that, hamra date have low water

content and could be good for long term storage com-

pared to other cultivars. The low moisture content would

not be more inclined to decay, since nourishments with

high dampness substance are more inclined to perish-

ability. It might be pro table in perspective of the speci-

men timeframe of realistic usability (Shaba et al., 2015).

However, Berhi had highest moisture content among the

evaluated verities. Similarly, previous studies have been

reported moisture content 10%- 25%.

This indicates

that, our results were in accordance with the previous

studies (Rehman et al., 2012; Al-Harrassi et al., 2014).

The ash content of the selected varieties was found to

be in the range of 1.31% ± 0.09 - 2.50% ±0.53. Ghnimi

S et al., 2017 reported ash content of date fruits in the

range of 1.4 % - 2.3%. However, earlier studies reported

ash content of various date fruits varieties ranging from

0.9 % - 2.0 % (Al-Harrasi et al., 2014). This results was

in agreement with our obtained quanti cation.

Total protein and fat content: Total protein content

was determined and it was found that, among the tested

sample Hamra date had highest amount of protein 4.34

%

± 0.06. However, Roshodyyah had lowest amount of

protein 2.29%

a

± 0.04. Statistically it was found that,

all the samples were signi cantly different at p < 0.05.

High content of protein in hamra varieties suggest that,

it could be of good potential for nutritional bene ts.

Moreover, earlier studies reported average protein con-

tent of fresh and dried dates is 1.50 - 2.14%, respec-

tively (Kazi et al., 2015). On the other hand our result

showed that, tested samples had results ranging from

2.29-4.34. Our results were in accordance with previous

studies (Al-Harrasi et al., 2014). Fat content was found

to be signi cantly different at p < 0.05. The fat content

in several date fruits varieties ranged from 0.3% -0.6%.

Similarly, previous studies reported percentage of fat in

accordance with our results (Assirey 2015; Khalid et al.,

2016).

Total bre content: Table 1 showed that, the percent-

age of total bre was adequate and ranged from 4.39%

- 5.13 %. Total bre content for all the varieties of date

fruits found to be signi cantly different at p < 0.05.

However, Shebeby variety had signi cantly higher (p <

0.05) than the other varieties. Moreover, Barni was sig-

ni cantly lower (p < 0.05) than the rest of the selected

varieties. Al-Harrasi 2014 reported average total bre

content in date fruits was 2.5%, this was lower than our

reported values. This could be due to environmental as

well as duration of fruits collection. On the other hand,

few studies suggested that, the total average ber could

be from 5%- 8% (Nasir et al., 2015).

Total carbohydrate content and monosaccharide con-

tent: Our result showed that, all the samples were sig-

ni cantly different at p < 0.05 as presented in table 2.

Moreover, highest carbohydrate contents were found in

Hamra dates and were signi cantly higher (p < 0.05)

than the other varieties. In addition to that, Helwah

dates had low amount of carbohydrates than rest of the

varieties. On the other hand monosaccharide sugar was

found to be highest in Helwah Hail followed by Deglet

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS 267

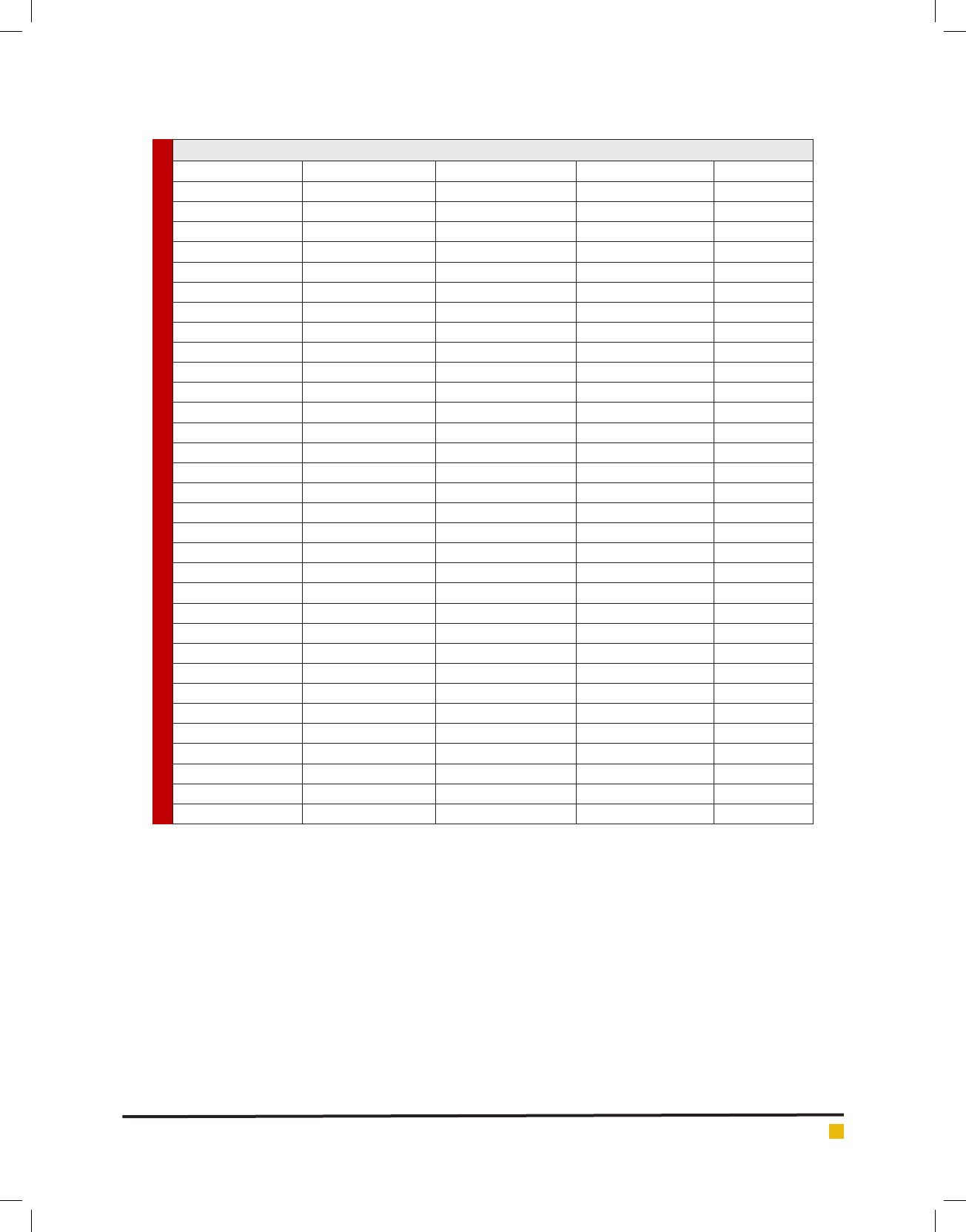

Table 3. Mineral analysis of date fruits

Sample Calcium (%) Magnesium (%) Sodium (%) Potassium (%)

Nabtat Saif 0.0122i ± 0.00021 0.0051e ± 0.00012 0.0538 s ± 0.00100 0.72 n ± 0.013

Khlas 0.0102g ± 0.00021 0.0061f ± 0.00012 0.0355 m ± 0.00062 0.43 d ± 0.008

Hamra 0.0091 f ± 0.00015 0.0122 k± 0.00021 0.0517 r ± 0.00095 0.76 o ± 0.014

Ajwah 0.0182n ± 0.00032 0.0040 d ± 0.00006 0.0203 f ± 0.00038 0.53 g ± 0.009

Shaishi 0.0162m ± 0.00032 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0172 d ± 0.00032 0.56 ij ± 0.010

Barni 0.0132j ± 0.00026 0.0030 c ± 0.00006 0.0385 o ± 0.00068 0.96 u ± 0.017

Sabbakah 0.0152l ± 0.00026 0.0030 c ± 0.00006 0.0172 d ± 0.00032 0.78 p ± 0.014

Seghae 0.0142k ± 0.00026 0.0061 f ± 0.00012 0.0182 e ± 0.00032 0.78 p ± 0.014

Roshodyyah 0.0122i ± 0.00021 0.0040 d ± 0.00006 0.0223 h ± 0.00042 0.53 gh ± 0.009

Nabtat Ali 0.0112 h± 0.00021 0.0071 g ± 0.00010 0.0436 u ± 0.00079 0.81q ± 0.014

Umm-Hamam 0.0091f ± 0.00015 0.0051 e ± 0.00012 0.0203 f ± 0.00038 0.40 c ± 0.007

Meskany 0.0091 f ± 0.00015 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0213 g ± 0.00036 0.47 e ± 0.008

Rezazy 0.0142 k ± 0.00026 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0406 p ± 0.00074 0.67 m ± 0.012

Asailah 0.0091f ± 0.00015 0.0152 l ± 0.00026 0.0294 k ± 0.00053 0.46 e ± 0.008

Gasbah 0.0061c ± 0.00012 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0122 b ± 0.00021 0.19 a ± 0.003

Shaqraa 0.0071d ± 0.00010 0.0051 e ± 0.00012 0.0152 c ± 0.00026 0.55 i ± 0.010

Menei 0.0102g ± 0.00021 0.0030 c ± 0.00006 0.0152 c ± 0.00026 0.58 j ± 0.010

Sultanah 0.0081e ± 0.00015 0.0102 i ± 0.00021 0.0172 d ± 0.00032 0.52 g ± 0.009

Wannanah 0.0040b ± 0.00006 0.0061f ± 0.00012 0.0213 g ± 0.00036 0.48 e ± 0.009

Umm Kebar 0.0071d ± 0.00010 0.0061 f ± 0.00012 0.0203 f ± 0.00038 0.49 f ± 0.009

Dhahesyyah 0.0112h ± 0.00021 0.0010 a ± 0.00000 0.0385 o ± 0.00068 0.60 k ± 0.010

Helwah 0.0102g ± 0.00021 0.0030 c ± 0.00006 0.0284 j ± 0.00053 0.52 g ± 0.009

Helwah Hail 0.0152l ± 0.00026 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0406 p ± 0.00074 0.70 n ± 0.013

Helwah Baqqa 0.0102g ± 0.00021 0.0020 b ± 0.00006 0.0254 i ± 0.00047 0.53 gh ± 0.009

Shebeby 0.0081e ± 0.00015 0.0071g ± 0.00010 0.0182 e ± 0.00032 0.55 hi ± 0.009

Umm-Khashab 0.0102g ± 0.00021 0.0102i ± 0.00021 0.0426 q ± 0.00079 0.41 c ± 0.007

Fankha 0.0030 a ± 0.00006 0.0081 h ± 0.00015 0.0294 k ± 0.00053 0.63 l ± 0.011

Berhi 0.0071d ± 0.00010 0.0122 k ± 0.00021 0.0375 n ± 0.00068 0.64 l ± 0.011

Maktoomy 0.0122 I ± 0.00021 0.0030 c ± 0.00006 0.0324 l ± 0.00059 0.53 g ± 0.009

Sukkari 0.0081e ± 0.00015 0.0081 h ± 0.00015 0.0294 k ± 0.00053 0.25 b ± 0.004

Deglet Shewaish 0.0091f ± 0.00015 0.0071 g ± 0.00010 0.0294 k ± 0.00053 0.47 e ± 0.008

Majhoolah 0.0102 g± 0.00021 0.0051e ± 0.00012 0.0112 a ± 0.00021 0.55 i ± 0.010

Shewaish dates 56.67% and 56.62%, respectively. High

amount of monosaccharide sugar could be due to fresh-

ness of the sample. However, Majhoolah had 30.66%

monosaccharide sugar, this was signi cantly lower (p <

0.05) than the other varieties. Similarly, it was observed

that, earlier reports suggested total carbohydrate content

as well as monosaccharide sugar ranged from 50-70%,

this was in accordance with our results (Al-Harrasi et al.,

2014; Assirey, 2015; Khalid et al., 2016).

Mineral Analysis: Results of mineral analysis (calcium,

magnesium, sodium and potassium) showed that, all the

date varieties are rich source of minerals. Moreover, our

result showed that, all the date varieties were signi -

cantly different at p p < 0.05 as presented in table 3. In

addition to that, we found that, calcium was highest in

Ajwa dates , when compared with other selected vari-

eties. However, Fankha dates had lowest calcium con-

centration 0.0030%. In case of magnesium, Asailah was

found to have 0.0152% followed by lowest concentra-

tion of magnesium in Shaishi and some of ther varie-

ties of dates. Sodium was quanti ed highest in Nabtat

Saif 0.0538% followed by 0.0122% in Gasbah dates.

In addition to that, potassium was found be highest in

Barni dates 0.96%. Similarly, all the quanti ed minerals

reported were in accordance with earlier studies (Nasir

et al., 2015; Parvin et al., 2015; Shaba et al., 2015).

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

268 NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

CONCLUSION

Dates fruits are an extremely famous and oldest food

known to human beings and it has been proven to con-

tain high levels of carbohydrate, proteins, vitamins,

crude bers and essential minerals. Therefore, dates not

only delicious with sweet taste and a eshy mouth feel

but also considered as an almost ideal food that provides

a wide range of essential nutrients with many potential

health bene ts. Our study revealed baseline informa-

tion on different date varieties grown in Hail region of

Saudi Arabia. The results showed that, ash and protein

content was highest in Ajwah (2.50 ± 0.53) and Hamra

(4.34 ± 0.06) dates, respectively. Similarly, monosac-

charaides sugar content was found highest in Helwah

Hail and Deglet Shewaish. Mineral analysis showed

that Ajwah date fruits, Asilah, Nabtat Saif and Barni

had high amount of calcium, magnesium, sodium and

potassium respectively. However, lesser known varieties

grown in this region can be improved through better

horticulture practices as a valuable product and results

obtained from the investigation in this study may help

in expanding the utilization of these date palm varieties

for commercial gain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Sheikh Ali Al-Jumaiah

Chair for Sustainable Development in Agricultural Com-

munities, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any con ict of interest.

REFERENCES

AOAC (Association of Of cial Analytical Chemists) (2006).

Of cial Methods of Analysis, 18th edn. (Gaithersburg, S. edn).

AOAC Press, Washington DC., USA.

Al-Abdoulhadi, I.A., Al-Ali, S., Khurshid K., Al-Shryda F., Al-

Jabr A.M., Abdallah A.B. (2011). Assessing fruit characteris-

tics to standardize quality norms in date cultivars of Saudi

Arabia. Indian Journal of Science and Technology. 4(10):1262-

1266.

Assirey E.A.R. (2015). Nutritional composition of fruit of 10

date palm,(Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars grown in Saudi

Arabia. Journal of Taibah University for Science 9:75–79.

Allbed, A., Kumar, L., and Shabani, F. (2017). Climate change

impacts on date palm cultivation in Saudi Arabia. Journal of

Agricultural Science. 1-16. doi:10.1017/S0021859617000260.

Al-Shreed, F., Al-Jamal, M., Al-Abbad, A., Al-Elaiw, Z., Abdal-

lah A. B., and Belaifa, H. (2012). A study on the export of Saudi

Arabian dates in the global markets. Journal of Development

and Agricultural Economics. 4(9):268-274.

Al-Harrasi, A., Rehman, N., Hussain, J., Khan, A. L. Al-Rawahi,

A. Gilani, S. A., Ali, L. (2014). Nutritional assessment and anti-

oxidant analysis of 22 date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) varieties

growing in Sultanate of Oman. Asian Paci c Journal of Tropi-

cal Medicine. (Suppl 1): S591-S598.

Aldjain, I.M., Al-Whaibi, M. H., Al-Showiman, S. S. & Sid-

diqui, M. H. (2011). Determination of heavy metals in the fruit

of date palm growing at different locations of Riyadh. Saudi

Journal of Biological Sciences. 18:175–180. doi:10.1016/j.

sjbs.2010.12.001.

Al-Hazzaa, H. M., Abahussain, N. A. Al-Sobayel, H.I., Qahwaji,

D. M., and Musaiger, A.O. (2012). Life style factors associated

with overweight and obesity among Saudi adolescents. Public

Health. 12: 354.

Ahamad S. R., Al-Ghadeer, A. R., Ali, R., Qamar, W., Aljarboa,

S. (2016).

Analysis of inorganic and organic constituents of

myrrh resin by GC–MS and ICP-MS: An emphasis on medici-

nal assets. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 25: 788-794.

Bashir, A., Ashraf, S.A., Khan M. A., and Azad, Z.R.A.A. (2015).

Development and compositional analysis of protein enriched

soybean-pea-wheat our blended cookies. Asian Journal of

Clinical Nutrition. 7: 76-83.

Chandrasekaran, M., Bahkali, H. A. (2013). Valorization of date

palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit processing by-products and

wastes using bioprocess technology – Review. Saudi Journal

of Biological Sciences. 20:105–120.

Hamad, I., AbdElgawad, H., Al Jaouni S., Zinta G., Asard,

H., Hassan, S., Hegab, M., Hagagy N., and Selim, S. (2015).

Metabolic analysis of various date palm fruit (Phoenix dac-

tylifera L.) cultivars from Saudi Arabia to assess their nutri-

tional quality. Molecules. 20:13620-13641. doi:10.3390/mol-

ecules200813620.

Ghnimi, S., Umer, S., Karim, A., Kamal-Eldin, A. (2017). Date

fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): An underutilized food seeking

industrial valorization. NFS Journal 6:1–10.

Khalid, S., Ahmad, A., Masud, T., Asad, M. J., and Sandhu, M.

(2016). Nutritional assessment of Ajwa date esh and pits in

comparison to local varieties. The Journal of Animal & Plant

Sciences. 26(4):1072-1080.

Nasir, M. U., Hussain, S., Jabbar, S., Rashid, F., Khalid, N.,

Mehmood, A. (2015). A review on the nutritional content,

functional properties and medicinal potential of dates. Science

Letters. 3(1):17-22.

Parvin, S., Easmin, D., Sheikh, A., Biswas, M., Jahan, M. G. S.,

Islam, M. A., Shovon, M.S. (2015). Nutritional analysis of date

fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in perspective of Bangladesh.

American Journal of Life Sciences. 3(4): 274-278.

Rehman Z, Salariya A.M, Zafar, S.I. (2012). Effect of process-

ing on available carbohydrate content and starch digestibil-

ity of kidney beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Food Chemistry.

73:351–355.

Ahmed Ali Alghamdi et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT DATE FRUITS 269

Shaba, E. Y., Ndamitso, M. M., Mathew, J. T., Etsunyakpa, M.

B., Tsado, A. N., and Muhammad, S. S. (2015).

Nutritional and

anti-nutritional composition of date palm (Phoenix dactyl-

ifera L.) fruits sold in major markets of Minna Niger State,

Nigeria. African Journal of pure and applied Chemistry. 9 (8):

167-174.

Taha, K.K., and Al Ghahtani F.M. (2015). Determination of the

elemental contents of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) from

Kharj Saudi Arabia. World Scienti c News. 6: 125-135.

Vayalil PK. (2012). Date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera Linn.): an

emerging medicinal food. Critical Review of Food Science and

Nutrition. 52: 249-271.