Medical

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 10(3): 341-345 (2017)

Assessment of short term prognosis in patients with

upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Saeid Hashemieh (MD)

1

, Ramtin Moradi (MD)

2

, Davood Karimi Hosseini (MD)

3

and

Habib Malek Pour (MD)

1

*

1

Department of Internal Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences

2

Mashhad Azad University School of Medicine

3

Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, USA

ABSTRACT

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a medical emergency. There is no precise information of its prevalence

and prognosis in patients. The aim of present study was to investigate the prognostic factors of UGIB in patients. In

this prospective observational study 75 patients with UGIB referred to Hospital. Demographic and clinical data of

them were recorded and analyzed. Mortality rate in rst hospitalization was 16% and in one-month follow up was

4%. There was no signi cant association between age and gender with duration of hospitalization and one-month

prognosis (p>0.05). Mortality was associated with acute abdomen and orthostatic hypotension I admission time, pep-

tic ulcer in endoscopic evaluation, active bleeding, ICU admission and need to second endoscopy (p<0.05). Erosive

gastritis, need to emergent surgery and use of NSAIDs signi cant increase of mortality rate (p<0.05). It seems admis-

sion time signs and symptoms, hemodynamic and coagulation status, endoscopic results and need to re-endoscopic

evaluation are more prognostic factors in patients with UGIB.

KEY WORDS: SHORT TERM PROGNOSIS, UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL, BLEEDING

341

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author:

Received 27

th

June, 2017

Accepted after revision 27

th

Sep, 2017

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2017: 4.31 Cosmos IF: 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2017. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at:

http//www.bbrc.in/

DOI: 10.21786/bbrc/10.3/1

INTRODUCTION

The UGIB bleeding occurs frequently and is a common

cause of hospitalization or inpatient bleeding. Such

bleeding results in substantial patient morbidity, mor-

tality and healthcare expense. Ulcer disease is the most

common cause of severe UGIB, causing about 40-50%

of cases and UGIB is the most common complication of

peptic ulcer disease (Kovacs and Jensen, 2008). The ini-

tial management of the patient with UGIB should include

evaluation of severity of the hemorrhage, patient resusci-

tation, a brief medical history and physical examination,

342 ASSESSMENT OF SHORT TERM PROGNOSIS IN PATIENTS WITH UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Saeid Hashemieh et al.

and consideration of possible interventions (Lin et al.

2005). This lack of evidence is re ected in the literature.

In databases and in product monographs for corticoster-

oids, peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding may or may

not be described as possible adverse effects (de Abajo

etal. 2013).

GI bleeding, bleeding peptic ulcer and perforation

are feared complications of peptic ulcer disease, associ-

ated with considerable morbidity and mortality (Lanas

etal. 2011). In clinical recommendations, an association

between corticosteroid use and peptic ulcer has been

described as unlikely, and the value of antiulcer prophy-

laxis has been questioned due to a low bleeding risk

(Martinek etal. 2011). Non-steroidal anti-in ammatory

drugs (NSAID) use and Helicobacter pylori infection are

the most important risk factors for peptic ulcer disease.

Bleeding or perforation is also seen as complications to

stress ulcers among patients with critical illness in inten-

sive care units. GI bleeding and perforation are assumed

to occur when ulcers erode into underlying vessels (Hal-

liday etal. 2010). It is reported a high late as well as early

mortality for upper GI bleeding, with very poor longer

term prognosis following bleeding due to malignancies

and varices. Aetiologies with the worst prognosis were

often associated with high levels of social deprivation

(Roberts etal. 2012).

The aetiology of hemorrhage can be broadly con-

sidered to be non-variceal or variceal in origin. In the

upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage accounts for85%

of presentations, the major causative lesion being pep-

tic ulcer disease, followed by erosive diseases such as

oesophagitis, gastritis and duodenitis (Jairath & Barkun,

2012). Risk factors for developing upper gastrointesti-

nal hemorrhage include old age, socio-economic disad-

vantage, co-morbidities such as chronic renal disease,

Helicobacter pylori infection and several pharmaceuti-

cal agents including NSAIDS, aspirin, cyclo-oxygenase

(COX) 2 inhibitors and anticoagulants. The remaining

presentations (10–15%) are secondary to variceal hem-

orrhage in patients with liver cirrhosis (Holcomb etal.

2015).

Coagulopathy exacerbates bleeding and should be

corrected with blood products. Massive bleeding man-

dates emergency endoscopy. Emergency endoscopy

is performed as soon as the patient is stabilized after

initial resuscitation. In patients with exigent bleed-

ing, endoscopy can be performed during resuscitation

(Button et al. 2011). Local studies indicate that as the

incidence of upper GI bleeding has increased over time

(Hearnshaw et al. 2010). There is also current interest

in whether prognosis for emergency disorders varies

according to the day of admission, the size of hospi-

tal and the distance travelled to hospital although lit-

tle has been reported about these for upper GI bleed-

ing (Shaheen etal. 2009). So, the main objective of this

study was to establish short term prognosis in patients

with UGI bleeding in 1 month follow-up period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This prospective observational study was done to assess

short term prognosis in 75 patients with upper gastro-

intestinal bleeding referred to the Imam Husein Hospita,

(Tehran, Iran) during the 2015-16. The demographic

information was collected using check list based on

patient’s background, Para clinic information, hos-

pitalization and follow-up data. Correlation between

sex, gender, age, disease and medication background,

gastrointestinal disorder, smoking or alcohol drinking,

blood factors (hemoglobin, PT, PTT, INR and platelet)

and endoscopic ulceration are determined at the arrival

and after 1 month. Data is analyzed by repeated measure

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 16.0

for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For treat-

ment showing a main effect by ANOVA, means com-

pared by Tukey–Kramer test. P<0.05 was considered as

signi cant differences between treatments.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

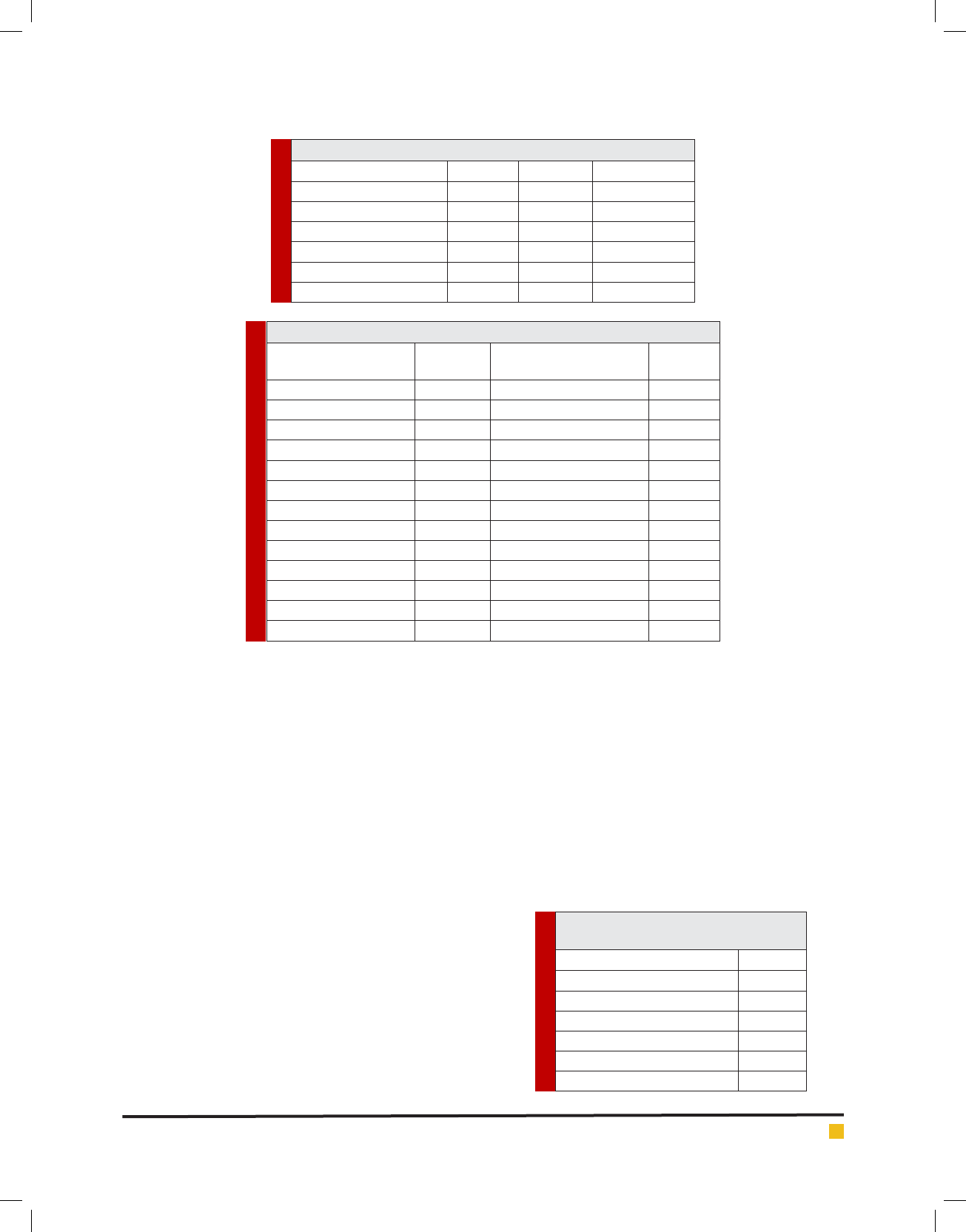

As seen in the current study, among 75 patients, 54 male

(72%) and 21 women (28%) were include into the study.

The mean age of the patients was 61.2 ± 18.6 years old

(P=0.4).in this study, 37 (49.3%) had hematoma while 46

(61.3%) had melena, 11 (14.7%) Hematochezia and 27

(36%) with active bleeding were referred to the hospi-

tal. In the initial investigation the mean blood pressure

and diastolic pressures were 116.1±19.2 and 69.8±23.4

mmHg, respectively. Mean heart rate was 81.2±27.7/

min. the clinical results of the patients included into the

study is presented in table 1. According to the data, the

man HB at the beginning and end of the study were 9.3

± 2.9 and 9.8 ± 2.01 mg/dl, respectively. The mean PT,

PTT and INR were 14.7 ± 8.7, 31.9 ± 25.2 and 1.5 ± 1.4,

respectively.

The patient’s distribution based on disease back-

ground is presented in table 2. According to the data,

Hypertension and Cardiovascular disease were the most

frequent among them. Also, ulcer was the prominent

digestive disease 27 (36%). For family background for

gastrointestinal disease, GI cancer 4 (5.3%) was the most

report.

Based on the endoscopic observation, clean base

and gastritis were the more problem 23 (30.7%) and 22

(29.3%) in the patients.

In this study, 4 patients (5.3%) needed for urgency

surgery and 33 (44%) for packed cell. During the study,

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS ASSESSMENT OF SHORT TERM PROGNOSIS IN PATIENTS WITH UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING 343

Saeid Hashemieh et al.

Table 1. The clinical results of the patients included into the study

Factor Minimum Maximum Mean ± Sd

Hb (at arrival) (mg/dl) 2.9 16 9.3 ± 2.9

Hb (after treatment) (mg/dl) 6.8 15.7 9.8 ± 2.01

PT 1.3 50 14.7 ± 8.7

PTT 1 120 31.9 ± 25.2

INR 1 9.3 1.5 ± 1.4

Platelet 31500 479000 213200 ± 111800

Table 2. The patients distribution based on disease background

Factor

N (%)

Family background for

Gastrointestinal disease

N (%)

Disease background Ulcer 2 (2.7)

Diabetes 31 (41.3) Gastrointestinal cancer 4 (5.3)

Hyperlipidemia 17 (22.7) Intestinal ulcers 2 (2.7)

Hypertension 41 (54.7) Medication Background

Cardiovascular disease 41 (54.7) NSAID 20 (26.7)

Cirrhosis 8 (10.7) SSRI 13 (17.3)

Hepatitis 5 (6.7) Warfarin 10 (13.3)

Digestive disorders Steroid 2 (2.7)

Ulcer 27 (36) Opioid therapy

Intestinal ulcers 8 (10.7) Alcohol 16 (21.3)

Gastrointestinal cancer 6 (8) Opiates 31 (41.3)

Gastrointestinal bleeding 8 (10.7) Smoking 5 (6.7)

Methadone 1 (1.3)

Table 3. The endoscopic observation in the

patients

Endoscopic results N (%)

Pigmented ulcer Pigmented ulcer 2 (5.3)

Clean base 23 (30.7)

Gastritis 22 (29.3)

Tearing 2 (2.7)

Gastric varices 7 (9.3)

Visiblessle ulcer 8 (10.7)

16 patients needed for hospitalization (21.3%) in the

ICU. 6 (8%) of them had bleeding and 11 (14.7%) sub-

sequent endoscopy. Hospitalization period was 5.5±2.5

days and 12 deaths during hospitalization and 3 deaths

in 1 month follow-up were reported. After a month fol-

low-up, digestive signs 32 (50.8%), bleeding 32 (50.8%),

sever moral 2(3.1%), re-endoscpoy 2(3.1%), re-hospital-

ization 2(3.1%), and death 3(3.4%) were recorded. No

signi cant difference detected between sex, age, family

background, medication, Hematochezia, hematoma and

melena before and after the study (P>0.05). No signif-

icant difference observed in group aged <60 and >60

years old in mentioned factors (P>0.05).

According to the results, a signi cant correla-

tion observed between blood pressure and bad moral

(P<0.001), GI bleeding (P=0.018), alcohol (P=0.04),

Opium administration (P=0.000), NSAIDs (P=0.036),

ulcer incidence in primary endoscopy (P=0.003), Gas-

tritis (P=0.008), emergency surgery (P=0.000), ICU care

(P=0.000), re-bleeding (P=0.010) and need for subse-

quent endoscopy (P=0.000). A correlation exist between

opium administration in 1 month follow-up and endo-

scopic ulcer (P=0.07). A signi cant correlation reported

between death and peritonitis (P=0.046), hypotension

(P=0.053), gastric ulcer in endoscopy (P=0.04), bleeding

(P=0.023), ICU care (P=008) and no differences found in

re-endoscopy (P=027), NSAIDs (P=056), gastritis (P=073)

and emergency surgery (P=053).

According to the results, mortality rate in rst hos-

pitalization was 16% and in one-month follow up was

4%. There was no signi cant association between age

and gender with duration of hospitalization and one-

month prognosis. Mortality was associated with acute

abdomen and orthostatic hypotension I admission time,

peptic ulcer in endoscopic evaluation, active bleeding,

ICU admission and need to second endoscopy. Erosive

gastritis, need to emergent surgery and use of NSAID

s

344 ASSESSMENT OF SHORT TERM PROGNOSIS IN PATIENTS WITH UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Saeid Hashemieh et al.

signi cant increase of mortality rate. It seems admission

time signs and symptoms, hemodynamic and coagula-

tion status, endoscopic results and need to re-endoscopic

evaluation are more prognostic factors in patients with

UGIB.

In a study, Lanas etal. (2011) on 2660 patients (64.7%

men; mean age 67.7 years) signi cant differences reported

on across countries in bleeding continuation ⁄ re-bleed-

ing (range: 9–15.8%) or death (2.5–8%) at 30 days were

explained by clinical factors (number of comorbidities, age

> 65 years, history of bleeding ulcers, in-hospital bleed-

ing, type of lesion or type of concomitant medication).

Other factors (country, size of hospital, pro le of team

managing the event, endoscopic and/or pharmacological

therapy received) were not able to affect these outcomes

(Loper do etal. 2009). Risk factors that have been previ-

ously identi ed to be predictive of bleeding continuation

and re-bleeding include presence of comorbidities out-

comes (Loper do etal. 2009) endoscopy-observed high-

risk stigmata of bleeding; worse health status at admis-

sion; bleeding from a peptic ulcer ( Viviane and Alan,

2008) a nding of bright blood during rectal examination

and in nasogastric tube aspirate; smoking; failure to use

PPIs postendoscopy; postendoscopy use of intravenous

or low molecular-weight heparins and low endoscopist

experience (Travis etal. 2008).

A number of these previously identi ed predictive

factors were con rmed in UGIB (i.e. presence of comor-

bidities, bleeding from a duodenal ulcer), and a number

of new predictors of bleeding continuation⁄ re-bleeding

were characterized: older age (>65 years), presentation

with haematemesis and a history of UGIB at baseline

(Button etal. 2011). Previously characterized predictors

of mortality include older age; presence of, and increas-

ing number of, comorbidities; continued bleeding and

⁄ or re-bleeding and a nding of bright blood in the

nasogastric tube aspirate (Marmo etal. 2010). The pre-

dictive validity of older age and the presence of comor-

bidities were con rmed in UGIB; in fact, the presence of

comorbidities was by far the strongest predictor of mor-

tality in this patient population. Other factors identi ed

to be signi cantly predictive of mortality in this study

were presentation with clinical symptoms of acute upper

GI bleeding and alcohol abuse (Shaheen etal. 2009).

The overall rate of deaths due to GI complications

and the rate of deaths associated with NSAID/aspirin

use reported are lower than some frequently quoted

estimates from previous studies, despite the fact that

our gures include both upper and lower GI complica-

tions and also refer to low-dose aspirin use (Hawkey and

Langman, 2003).

There are a number of reasons that may account

for some of the discrepancies observed in the studies:

variation in prescribing practice by country; differences

in the extent of NSAID use and in the co-prescription

of gastroprotective drugs; decreasing GI complication

rates; and differences in study methodologies. Our data

would imply a lower NSAID consumption in Spain com-

pared with other countries. However, the annual NSAID

prescription rates in Spain are relatively high (35.4 mil-

lion) (Van Leerdam etal. 2003) and are proportionally

greater than rates reported in the United Kingdom and

50% of those reported in the United States (70 million),

despite Spain’s smaller population. In addition, the rate

of NSAID use among adults in Spain (20.6%) is simi-

lar than that determined in the United States (Estudio,

2000). Upper GI bleeding is one of the most important

emergency disorders with high rates of mortality during

the acute phase. Longer term increased risk of mortality

is partly due to very poor prognosis for malignancy and

variceal etiologies; although it also re ects an impact of

high levels of social deprivation and chronic co-morbid

disease among people with upper GI bleeding (Roberts

etal. 2012).

Survival over the three years was substantially poorer

than in the general population for most etiologies of

bleeding, with the possible exception of ‘complications

of analgesics, antipyretics and anti-in ammatory drugs’

and duodenal ulcers, which were both less prevalent

among deprived quintiles than most of the other eti-

ologies. Relative survival was worse for duodenal ulcer

than for gastric ulcer in the rst few months after admis-

sion, but it was better than for gastric ulcer bleeds in the

longer term. This nding is consistent with a large sin-

gle-center study of surgery for peptic ulcer which found

increased longer term mortality for gastric ulcer but not

for duodenal ulcer (Stae¨l von Holstein etal. 1997). In

conclusion it seems admission time signs and symp-

toms, hemodynamic and coagulation status, endoscopic

results and need to re-endoscopic evaluation are more

prognostic factors in patients with UGIB.

REFERENCES

Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, et al. 2011 Hospitalized

incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding

from1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther 2011; 33: 64–76.

Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, Goldacre MJ, Akbari A,

Dsilva R, Macey S, Williams JG 2011. Hospitalized incidence

and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999

to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33:

64–76

Carmona L. Estudio 2000 EPISER. Madrid: Spanish Society of

Rheumatology; 141–54.

De Abajo FJ, Gil MJ, Bryant V, et al.2013 Upper gastrointesti-

nal bleeding associated with NSAIDs, other drugs and interac-

tions: a nested case-control study in a new general practice

database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69:691–701.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS ASSESSMENT OF SHORT TERM PROGNOSIS IN PATIENTS WITH UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING 345

Saeid Hashemieh et al.

Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Doyle LW.2010 Early (<8 days)

postnatal corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease

in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001146.

Hawkey CJ, Langman MJ 2003 .Non-steroidal anti-in amma-

tory drugs: Overall risks and management. Complementary

roles for COX-2 inhibitors and proton pump inhibitors. Gut

52(4):600–8.

Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF,

Palmer KR. 2010 Use of endoscopy for management of acute

upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: results of a nation-

wide audit. Gut 59: 1022–9.

Holcomb, J.B., Tilley, B.C., Baraniuk, S. etal. (2015) Transfu-

sion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a

1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the

PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313, 471–82.

Kovacs TOG, Jensen DM. 2008 The short-term medical man-

agement of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Drugs 68 (15): 2105-2111.

Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Polo-Tomas M, etal. 2011 The

changing face of hospitalisation due to gastrointestinal bleed-

ing and perforation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33:585–91.

Lin HJ, Lo WC, Cheng YC, etal. 2006 Role of intravenous ome-

prazole in patients with high- risk peptic ulcer bleeding after

successful endoscopic epinephrine injection: a prospective,

randomized, comparative trial. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 500-5.

Loper do S, Baldo V, Piovesana E, etal. 2009 Changing trends

in acute upper-GI bleeding: a population-based study. Gastro-

intest Endosc 70: 212–24.

Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, etal. 2010 Predicting mortality

in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeders: validation of

the Italian PNED score and prospective comparison with the

Rockall score. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1284–91.

Martinek J, Hlavova K, Zavada F, etal. 2010 A surviving myth—

corticosteroids are still considered ulcerogenic by a majority of

physicians. Scand J Gastroenterol 45:1156–61.

Roberts SE, Button LA, Williams JG (2012) Prognosis follow-

ing Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. PLoS ONE 7(12): e49507.

doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0049507

Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. 2009 Weekend versus

weekday admission and mortality from gastrointestinal hem-

orrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 7: 303–10.

Stae¨l von Holstein C, Anderson H, Ahsberg K, Huldt B (1997)

The signi cance of ulcer disease on late mortality after partial

gastric resection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 33–40.

Travis AC, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR.2008 Model to predict

rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for non-variceal

upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol

23: 1505–10.

Van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, etal. 2003 Acute

upper GI bleeding: Did anything change? Time trend analysis

of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between

1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol;98(7):1494–9.

Viviane A, Alan BN. 2008 Estimates of costs of hospital stay

for variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in

the United States. Value Health 11: 1–3.