Biotechnological

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 10(2): 187-191 (2017)

PCR based analysis of Haemobartonellosis (

Candidatus

mycoplasma haematoparvum

and

Mycoplacma

haemocanis

) and its prevalence in dogs in Isfahan, Iran

Sayed Reza Hosseini,

1

Arman Sekhavatmandi

2

and Faham Khamesipour

3,4

1

Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Shahrekord Branch, Islamic Azad University,

Shahrekord, Iran

2

Graduated of Veterinary Medicine, Shahrekord Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrekord, Iran

3

Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran

4

Department of Pathobiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

ABSTRACT

The present study was conducted to determine prevalence of Candidatus mycoplasma haematoparvum and Myco-

placma haemocanis in dogs in Isfahan (Central province of Iran). Total 294 dogs were the materials of the study.

To determine molecular and haematological parameters, 2 ml blood with and without anticoagulant were taken

according to technique from vena cephalica antebrachii. Candidatus mycoplasma haematoparvum and Mycoplacma

haemocanis was detected in blood smears preparations of 26 (8.82%) by Geimsa staining and (20.06%) by PCR. Based

on the 16S rDNA sequence, a speci c PCR assay was developed.

KEY WORDS: HAEMOBARTONELLOSIS, DOGS, IRAN, PCR

187

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: borji_milad@yahoo.com

Received 21

st

March, 2017

Accepted after revision 21

st

June, 2017

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2017: 4.31 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2017. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

INTRODUCTION

The organisms formerly known as Haemobartonella and

Eperythrozoon spp. are small, pleomorphic bacteria that

parasitize red blood cells of a wide range of vertebrate

animals. Haemobartonellosis, infectious anaemia of

dogs is caused by Candidatus mycoplasma haematopar-

vum and Mycoplacma haemocanis, an anaplasma spe-

cies belonging to the rickettsia family. The infection is

characterized by extreme fatigue, depression, anorexia,

weight loss and anaemia and may cause death (Lumb,

2001; Neimark et al., 2001; Torkan et al., 2014).

The pathogen can be identi ed as small coccoids,

rings or strings on erythrocyte membrane or free in

188 PCR BASED ANALYSIS OF HAEMOBARTONELLOSIS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Hosseini, Sekhavatmandi and Khamesipour

plasma in Giemsa staining of blood smears (Murray

et al., 1995; Lumb, 2001).Mode of transmission has not

been clearly identi ed but bloodsucking arthropods like

ticks were the suspected vectors. Another possible mode

of transmission is close ghting among dogs. Intrauter-

ine and lactation-related transmission was also reported

(Neimark et al., 2002; Jane et al., 2005).Acute disease

presents with fever, anorexia, weight loss, jaundice,

apathy, adenopathy, motor incoordination and spleno-

megaly (North, 1978; Sykes et al., 2004). Chronic dis-

ease has atypical symptoms like anaemia, weight loss,

paraplegia, dehydration, hyperesthesia and depression

(Saykes et al., 2008). Latent form of the infection has

also been described (Pitulle et al., 1999).Diagnosis of

haemobartonellosis depends on clinical and hematologi-

cal ndings together with microscopic examination of

blood smears and speci c serological and PCR testing

for the pathogen (Lappin et al., 2006). Various antibiot-

ics were reported to be effective in the treatment of hae-

mobartonellosis. Haemobartonellosis was rst described

in 1953 in the United States (Splitter et al., 1956) but the

number of studies about incidence and prevalence of the

disease and the risk factors in transmission remains lim-

ited after 50 years (Kemming et al., 2004). In addition,

studies examining Candidatus mycoplasma haematopar-

vum and Mycoplacma haemocanis infection have not

been came across in this country except for one study

(Foley et al., 2001).Therefore, this study was planned to

investigate prevalence of Candidatus mycoplasma hae-

matoparvum and Mycoplacma haemocanis infection in

dogs.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study population consisted of 294 dogs (140 females,

154 males). To determine molecular and haematological

parameters, 2 ml blood with and without anticoagulant

were taken according to technique from V. cephalica. The

dogs were clinically examined and blood samples with

and without anticoagulant were drawn into tubes for

haematological and molecular analysis. Prepared blood

smears were stained with Geimsa method and examined

under light microscope according to the literature (Foley

et al., 2001).

Blood was processed for DNA extraction as described

by d’Oliveira et al. (1995). Brie y, 200: L of thawed

blood was washed 3-5 times by mixing with 0.5 mL PBS

(137mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 8.1mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM

KH2PO4, pH 7.4), each time followed by centrifugation

at maximum speed (13,000 rpm) for 5 min. After the

nal wash, the cell pellet was resuspended in 100: L of

lysis mixture (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 0.5%

Tween 20, and 100: g/mL of proteinase K). This mixture

was incubated overnight at 56ºC, followed by 10 min of

boiling to inactivate the Proteinase K and kept at -20ºC

until needed for PCR for ampli cation of the 16S rRNA

gene (Dean et al., 2008).

The DNA samples from cattle blood were used in PCR

reactions (Reverse line blot-PCR) to amplify any Ana-

plasma (or even any Ehrlichia) 16S rRNA gene present.

One primer set was used to amplify a 309-328 bp frag-

ment being part of the V1 region of the16S rRNA gene.

The forward primer was (EF416566) (5’-GAAACTAA-

GGCCATAAATGACGC -3’) for Mycoplacma haemocanis

and (HQ918288) (5’-ACGAAAGTCTGATGGAG-

CAATAC-3’) for Candidatus mycoplasma haematopar-

vum whereas the reverse primer was (5’- ACCTGTCAC-

CTCGATAACCTCTAC-3’) for Mycoplacma haemocanis

and (5’-TATCTACGCATTCCACCGCTAC-3’) for Candida-

tus mycoplasma haematoparvum. The 1xPCR reaction

constituents in a nal volume of 25: L were as follows:

1xPCR buffer (Invitrogen), 3.0 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen),

200: M each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, 100: M dTTP (ABgene)

and 100: M dUTP (Amersham), 1.25 U of Taq polymerase

(Invitrogen), 0.1U of UDG (Amersham), 25 pmol of each

primer and 2.5: L of template DN A. This was over laid

with about 12.5: L of mineral oil. Positive control DNA

(E. canis) from Molecular Biology Laboratory, Makerere

University and negative control (reaction constituents

without DNA) tests were included. The reactions were

performed using a three phase touchdown program as

previously described (Barker et al., 2009; Brinson et al.,

2001). The possible presence of ectoparasites on the dogs

was also looked for carefully. Statistical analyses were

done using SPSS for Windows.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Clinical signs including temperature, pulsation and

respiration rates were in normal ranges. Some of the

infected cats had anorexia and weight loss. Microscopic

examination revealed Candidatus mycoplasma haema-

toparvum and Mycoplacma haemocanis in 26 (8.82%)

cats. The animals had no ectoparasites on them. Baseline

haematological and biochemical ndings did not differ

after the treatment. Appearance of Candidatus myco-

plasma haematoparvum and Mycoplacma haemocanis in

Geimsa staining of blood smears is presented. According

to the results sex had no effect on the infection of the

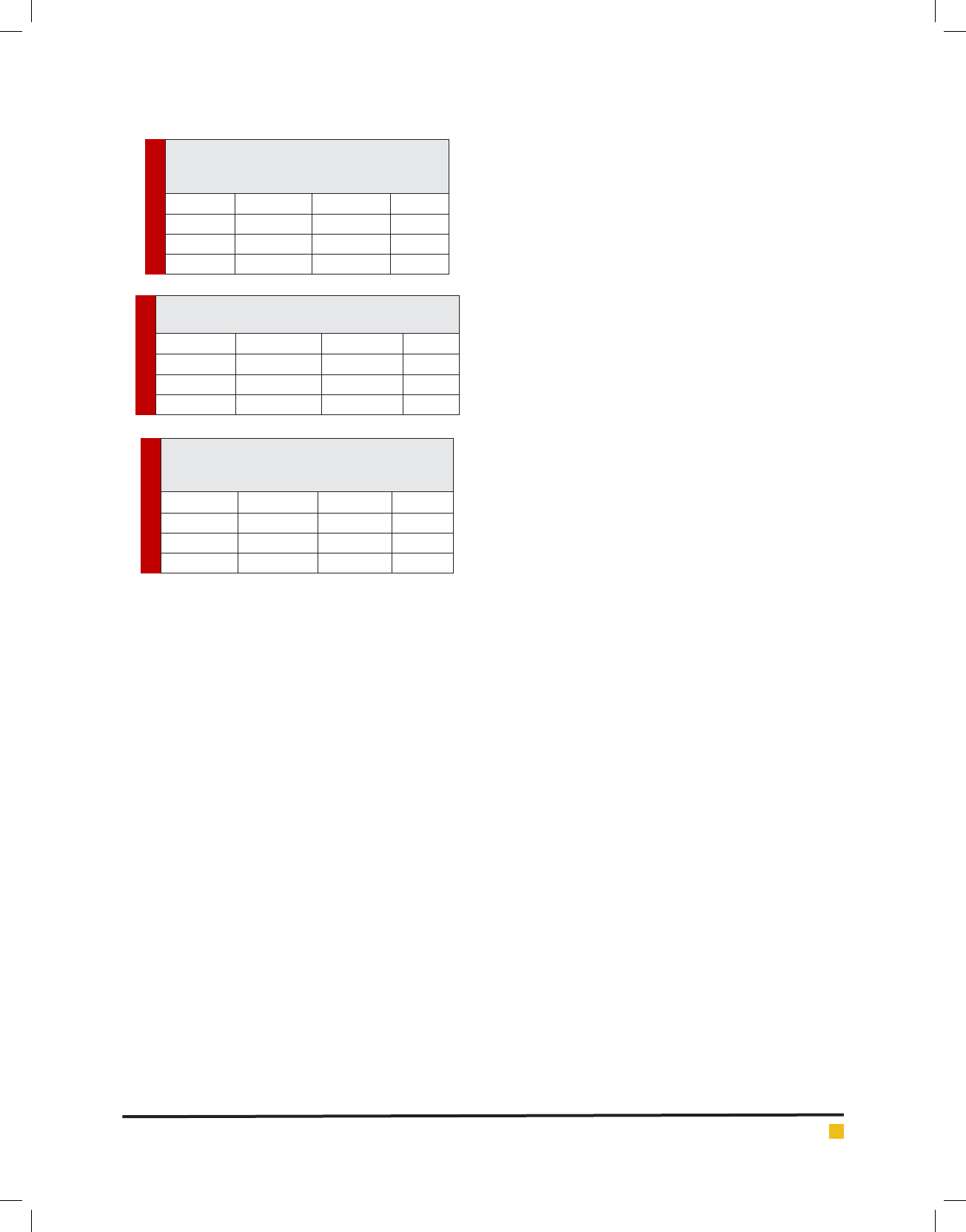

dogs (P > 0.05) (Tables1, 2 and 3).

In this study, we used histological methods and novel

molecular techniques to determine the regional preva-

lence and identity of Candidatus mycoplasma haema-

toparvum and Mycoplacma haemocanis. Of 294 samples,

66 supported ampli cation of parasite rRNA by PCR. 25

samples were then examined in parallel by microscopic

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS PCR BASED ANALYSIS OF HAEMOBARTONELLOSIS 189

Hosseini, Sekhavatmandi and Khamesipour

examination and PCR. One samples positive by initial

microscopic examination were not ampli ed by PCR.

Thirty-nine PCR-positive samples did not contain sarco-

cysts on initial microscopic examination, but additional

sections from these samples revealed sarcocysts in an

additional 12 samples. The partial sequence analysis of

the16S rRNA gene (both sequences had 150 bp) indi-

cated a homology of 100% between the PCR amplicons

of the positive samples and Candidatus Mycoplasma

haematoparvum.

The infection was most probably transmitted by

ectoparasites (Wood et al., 2006). In conclusion, a rate of

haemobartonellosis of 22.45% was determined in dogs

and it is believed that haemobartonellosis should always

be suspected in dogs presented to veterinary clinics with

non-speci c symptoms. In addition, serological investi-

gations should also be done in future studies to docu-

ment the prevalence of the disease in this country.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been increas-

ingly applied to detect these pathogens in both blood and

tick vectors instead of microscopy. Although a number

of publications report the use of PCR, most publications

are based on 6 original methods for all pathogens (Roura

et al.,2005; Sykes et al., 2005; Bauer et al., 2008; Sasaki

et al., 2008;). Many reports summarised compare PCR

detection with serology to demonstrate assay speci city.

However, the most suitable detection method depends

upon whether antigen or antibody detection is relevant

for the particular investigation, detection of parasites,

or current infection, prevalence studies or evidence of

exposure to parasites.

Although PCR is more sensitive than light microscopy

(Kemming et al., 2004), this method complicated post-

PCR detection methods to further enhance the sensitivity

and con rm the speci city of the PCR technique such as

PCR-ELISA and PCR-probe hybridisation. A quanti able

PCR technique referred to as real time PCR (also known

as 5’ Taq nuclease assays, uorogenic probe assays, or

TaqMan_ assays), are increasingly applied for the detec-

tion and identi cation of animal pathogens and do not

require post PCR electrophoresis or processing steps

(Gentilini et al.,2009).

Real time assays exploit the 5’ nuclease activity of

Taq DNA polymerase cleaving a dual labelled uores-

cent probe which has annealed to a speci c sequence

between two primers (Francino et al., 2006; Peters et

al., 2008; Wengi et al., 2008). To date, the applications

of real time PCR for the detection of tick borne disease

pathogens have been described for Theileria spp. and

Anaplasma spp. (Taber et al.,2009; Lako et al., 2010). It

may not be feasible for certain laboratories to use PCR-

ELISA, PCR-probe hybridisation or real time PCR assays

as the application of each of these methods requires spe-

ci c and expensive reagents and equipment. Microscopy

remains the most economic and sustainable method of

parasite detection for all laboratories.

This is the rst case of canine infection with Candi-

datus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in Iran. This organ-

ism, named Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum is

smaller (0.3 _m in diameter) and does not form chains

on the erythrocyte surface of dogs (Sykes et al., 2005).

The infection has been con rmed by methods of molec-

ular biology (Jensen et al., 2001). In France, a 15.4%

prevalence of haemoplasma infection in dogs, as well as

the presence of coinfection of both haemoplasmas, has

been registered using the PCR test (Kenny et al., 2004).

Further researches on haemotropic mycoplasmas are

indispensable, regarding that: haemoplasmas might act

as cofactors in the progression of retroviral, neoplastic

and immunologically mediated diseases; the factors of

the virulence and pathogenic mechanisms in the devel-

opment of these infections, as well as the functions of

the immunologic system, which is in this case again

responsible for the occurrence of new opportunistic

infections, are not known (Messick, 2004). Until now,

there is no evidence that canine haemoplasmas cause

human diseases, but regarding the fact that feline and

swine haemotropic mycoplasmas have zoonotic poten-

tial, future researches should be conducted in this direc-

tion (Xavier Roura et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2006).

The hemoplasma sample prevalence was signi cantly

higher in Switzerland (8.7%) than in Spain (2.5%) (Willi

Table 1. Distributions of the ndings according

to the sex of the cats Candidatus mycoplasma

haematoparvum by pcr

Sex Number Positive %

Female 140 12 8.57

Male 154 17 11.03

Total 294 29 9.86

Table 2. Distributions of the ndings according to

the sex of the cats Mycoplacma haemocanis by pcr

Sex Number Positive %

Female 140 15 10.71

Male 154 18 11.68

Total 294 33 11.22

Table 3. Distributions of the ndings according to

the sex of the cats Mycoplacma haemocanis and

Candidatus mycoplasma haematoparvum by pcr

Sex Number Positive %

Female 140 26 18.57

Male 154 33 21.42

Total 294 59 20.06

190 PCR BASED ANALYSIS OF HAEMOBARTONELLOSIS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Hosseini, Sekhavatmandi and Khamesipour

et al.,2006; Lako et al., 2010; Xavier et al., 2010). Risk

factors for infection included living in kennels, young

age, crossbreeding, and mange infection. Among the

PCR-positive dogs, 40% were infested with blood-suck-

ing arthropods. No association was found with anemia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Hamid Reza Arshad Riahi and Manochehr

Momeni for their enthusiastic support of this work.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no con icts of interest.

RREFRENCES

Barker E.N., S. Tasker, M. Day, S.M. Warman, K. Woolley, R.

Birtles, K.C. Georges, C.D. Ezeokoli, A. Newaj-Fyzul, M.D.

Campbell, O.A.E. Sparagano, S. Cleaveland and C.R. Helps.

(2009) Development and use of real-time PCR to detect and

quantify Mycoplasma haemocanis and ‘Candidatus Myco-

plasma haematoparvum in dogs. Veterinary Microbiology Vol.

140: Pages 167–170.

Bauer N., H.J. Balzer, S. Thure and A. Moritz. (2008) Prevalence

of feline hemotropic mycoplasmas in convenience samples of

cats in Germany. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Vol.

10: Pages 252–258.

Brinson J. J. and J. B. Messick., (2001) Use of a polymerase

chain reaction assay for detection of Haemobartonella canis in

a dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association

Vol. 218: Pages 1943–1945.

Dean R.S., C.R. Helps, T.J. Gruffydd Jones and S. Tasker. (2008)

Use of real-time PCR to detect Mycoplasma haemofelis and

Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum in the saliva and sali-

vary glands of haemoplasma-infected cats. Journal of Feline

Medicine and Surgery Vol. 10: Pages 413–417.

Foley J. E. and N. C Pedersen. (2001) Candidatus Mycoplasma

haemominutum, a low-virulence epierythrocytic parasite of

cats. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary

Microbiology Vol. 51: Pages 815–817.

Francino O., L. Altet, E. Sanchez-Robert, A. Rodriguez, L.

Solano-Gallego, J. Alberola, L. Ferrer, A. Sánchez and X.

Roura. (2006) Advantages of real-time PCR assay for diagnosis

and monitoring of canine leishmaniosis. Veterinary Parasitol-

ogy Vol. 137: Pages 214–221.

Gentilini F., M. Novacco, M.E. Turba, B. Willi, M.L. Bacci and

R. Hofmann-Lehmann. (2009) Use of combined conventional

and real-time PCR to determine the epidemiology of feline

haemoplasma infections in northern Italy. Journal of Feline

Medicine and Surgery Vol. 11: Pages 277–285.

Jensen W.A., M.R. Lappin, S. Kamkar and W.J. Reagan. (2001)

Use of a polymerase chain reaction assay to detect and dif-

ferentiate two strains of Haemobartonella felis in naturally

infected cats. American Journal of Veterinary Research Vol.

62: Pages 604-8.

Kemming G.I., J.B. Messick, G. Enders, M. Boros, B. Lorenz, S.

Muenzing, H. Kisch-Wedel, W. Mueller, A. Hahmann-Mueller,

K. Messmer and E. Thein. (2004) Mycoplasma haemocanis

infection—a kennel disease. Comparative Medicine Vol. 54:

Pages 404–409.

Kenny M.J., S.E. Shaw, F. Beugnet and S. Tasker. (2004) Dem-

onstration of two distinct haemotropic mycoplasmas in French

dogs. Journal of Clinical Microbiology Vol. 42: Pages 5397–

5399.

Lako B., A. Potkonjak, J. Balzer, A. Grozdana, D. Radsolava,

B. Topalski, M. Stevanevi and O. Stevanevi. (2010) First report

about canine infections with Candidatus mycoplasma haema-

toparvoum in Serbia. Acta Veterinaria (Beograd) Vol. 60, 5-6:

Pages 507-512.

Lumb W.V. (2001) More information on haemobartonellosis in

dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association

Vol. 219: Pages 732–733.

Messick J.B. (2004) Hemotrophic mycoplasmas (hemoplasmas):

a review and new insights into pathogenic potential. Veteri-

nary Clinical Pathology Vol. 33: Pages 2-13.

Murray R.G.E. and E. Stackebrandt. (1995) Taxonomic note:

implementation of the provisional status Candidatus for

incompletelydescribed procaryotes. International Journal of

Systematic Bacteriology Vol. 45: Pages 186–187.

Neimark H., J.K.E Ohansson, Y. Rikihisa and J.G. Tully. (2001)

Proposal to transfer some members of the genera Haemobar-

tonella and Eperythrozoon to the genus Mycoplasma with

descriptions of ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemofelis’, ‘Can-

didatus Mycoplasma haemomuris’, ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma

haemosuis’ and ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma wenyonii’. Interna-

tional Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology

Vol. 51: Pages 891–899.

Neimark H., K.E. Johansson, Y. Rikihisa and J.G. Tully. (2002)

Revision of haemotrophic Mycoplasma species names. Inter-

national Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology

Vol. 52: Pages 683.

North D. C. (1978) Fatal haemobartonellosis in a non-splenec-

tomized dog – a case report. Journal of Small Animal Practice

Vol. 19: Pages 769–773.

Peters I.R., C.R. Helps, B. Willi, R. Hofmann-Lehmann and S.

Tasker. (2008) The prevalence of three species of feline haemo-

plasmas in samples submitted to a diagnostics service as deter-

mined by three novel real-time duplex PCR assays. Veterinary

Microbiology Vol. 126: Pages 142–150.

Pitulle C., D. M.Citron, B. Bochner, R. Barbers and M. D. Apple-

man. (1999) Novel bacterium isolated from a lung transplant

patient with cystic brosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology

Vol. 37: Pages 3851–3855.

Roura X., E. Breitschwerdt, A. Lloret, L. Ferrer and B. Hegarty.

(2005) Serological evidence of exposure to Rickettsia,

Hosseini, Sekhavatmandi and Khamesipour

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS PCR BASED ANALYSIS OF HAEMOBARTONELLOSIS 191

Bartonella and Ehrlichia spp. in healthy or Leishmania infan-

tum infected dogs from Barcelona. The International Journal

of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine Vol. 3: Pages 129–

138.

Roura X., I.R. Peters, L. Altet, M.D. Tabar, E. N. Barker, M.

lanellas, C. R. Helps, O. Francino, S. E. Shaw and S. Tasker.

(2010) Prevalence of hemotropic mycoplasmas in healthy and

unhealthy cats and dogs in Spain. Journal of Veterinary Diag-

nostic Investigation Vol. 22: Pages 270–274.

Sasaki M., K. Ohta, A. Matsuu, H. Hirata, H. Ikadai and T. Oyam-

ada. (2008) A molecular survey of Mycoplasma haemocanis in

dogs and foxes in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. Journal of Proto-

zoology Research Vol. 18: Pages 57–60.

Seneviratna P., N. Weerasinghe and S. Ariyadasa. (1973)

Transmission of Haemobartonella canis by the dog tick, Rhipi-

cephalus sanguineus. Research in Veterinary Science Vol. 14:

Pages 112–114.

Sykes J.E., N.L. Bailiff, L.M. Ball, O. Foreman, J.W. George and

M.M. Fry. (2004) Identi cation of a novel haemotropic myco-

plasma in a splenectomized dog with hemic neoplasia. Jour-

nal of the American Veterinary Medical Association Vol. 224:

Pages 1946–1951.

Sykes J.E., L.M. Ball, N.L. Bailiff and M.M. Fry. (2005) Candida-

tus Mycoplasma haematoparvum, a novel small haemotropic

mycoplasma from a dog. International Journal of Systematic

and Evolutionary Microbiology Vol. 55: Pages 27-30.

Sykes J.E., J.C. Terry, L.L. Lindsay and S.D. Owens. (2008) Preva-

lences of various haemoplasma species among cats in the United

States with possible hemoplasmosis. Journal of the American

Veterinary Medical Association Vol. 232: Pages 372–379.

Splitter E. J., E. R. Castro and W. L. Kanawyer. (1956) Feline

infectious anemia. Veterinary medicine Vol. 51: Pages 17–22.

Tabar M.D., O. Francino, L. Altet, A. Sánchez, L. Ferrer and X.

Roura. (2009) PCR survey of vectorborne pathogens in dogs

living in and around Barcelona,an area endemic for leishmani-

osis, Veterinary Record Vol. 164: Pages 112–116.

Tasker S., C. R. Helps, M. J. Day, D. A. Harbour, S. E. Shaw,

S. Harrus, G. Baneth, R. G. Lobetti, R. Malik, J. P. Beau ls,

C. R. Belford and T. J. Gruffydd-Jones. (2003) Phyloge-

netic analysis of haemoplasma species – an international

study. Journal of Clinical Microbiology Vol. 41: Pages 3877–

3880.

Torkan, S., S. Nargesi and F. Khamesipour. (2014) The Com-

parative Study of the Treatment by Oxytetracycline and Home-

opathy on Induced Mycoplasma Haemofelis in Less than One-

Year-Old Cats. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary

Advances Vol. 6: Pages 97-102.

Wengi N., B. Willi, F.S. Boretti, V. Cattori, B. Riond, M.L.

Meli, C.E. Reusch, H. Lutz and R. Hofmann-Lehmann. (2008)

Real-time PCR-based prevalence study, infection follow-

up and molecular characterization of canine hemotro-

pic mycoplasmas. Veterinary Microbiology Vol. 126: Pages

132-41.

Willi B., S. Tasker, F.S. Boretti, M. G. Doherr, V. Cattori, M. L.

Meli, R. G. Lobetti, R. Malik, C. E. Reusch, H. Lutz and R. Hof-

mann-Lehmann. (2006) Phylogenetic analysis of ‘‘Candidatus

Mycoplasma turicensis’’ isolates from pet cats in the United

Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa, with analysis of risk

factors for infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology Vol. 44:

Pages 4430–4435.

Woods J.E., M.M. Brewer, J.R. Hawley, N. Wisnewski and M.

R. Lappin. (2006) Evaluation of experimental transmission of

‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’ and Mycoplasma

haemofelis by Ctenocephalides felis to cats. American Journal

of Veterinary Research Vol. 66: Pages 1008–1012.

Wu J., J. Yu, C. Song, S. Sun and Z. Wang. (2006) Porcine

eperythrozoonosis in China. Annals of the New York Academy

of Sciences Vol. 1081: Pages 280-5.