Health Science

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 10(2): 138-142 (2017)

The relationship between health literacy and general

health status of patients with type II diabetes

Milad Borji,

1

Asma Tarjoman,

2

Masoumeh Otaghi,

1

* Zeynab Khodarahmi

2

and Ali Shari

3

1

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Ilam University of Medical Sciences Ilam Iran

2

Student Research Committee Ilam University of Medical Sciences Ilam Iran

3

Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Ilam University of Medical

Sciences, Ilam Iran

ABSTRACT

Individuals with low health literacy are less aware of their own health status and receive fewer preventive services.

Furthermore, fewer chronic diseases are controlled in these individuals. This study aimed to investigate the relation-

ship between health literacy and general health status of patients with type II diabetes.In this descriptive-correlational

study, 250 patients with type II diabetes in Ilam were selected using convenience sampling. Tools used in this study

were the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) and General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ28). Data

analysis was conducted using the SPSS Software version 20, including t-test (for two groups of variables), ANOVA

(for more than two groups of variables), and correlation analysis.The results showed that 80 (32%), 102 (40.8%), and

68 (27.2%) patients with diabetes had inadequate, marginal, and adequate literacy, respectively. The ndings also

indicated that the means and standard deviations of patients’ health literacy scores were 31.38 ± 6.40 in terms of

calculations, 34.93 ± 7.45 in reading skill, and 6.30 ± 11.61 in general. There was a statistically signi cant relation-

ship between health literacy and general health status of patients (p < 0.001). Based on the results revealing average/

marginal health literacy and general health in most patients in the study, of cials must conduct more research to

improve health literacy and general health of patients.

KEY WORDS: HEALTH LITERACY, DIABETES, GENERAL HEALTH

138

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: otaghi-m@medilam.ac.ir

Received 12

th

March, 2017

Accepted after revision 19

th

June, 2017

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2017: 4.31 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2017. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

DOI: 10.21786/bbrc/10.2/24

Milad Borji et al.

INTRODUCTION

Health literacy is individual’s capacity for process,

obtain and understand basic about health information &

services and is necessary for good health (Kindig, Panzer

et al. 2004). Health literacy includes reading, listening,

analysis, and decision-making skills and the ability to

apply these skills in health positions, which is not neces-

sarily associated with education level or general reading

inability (Sihota and Lennard 2004). Inadequate health

literacy correlates with poorer individual health status

report, misuse of drugs and failure to comply with phy-

sician’s orders, poorer blood sugar control and increased

prevalence of individual reports of problems induced by

poor control, lower health knowledge, lower contribu-

tion in deciding on treatment, less expression of health

concerns, and worse relationship with physicians(Kindig,

Panzer et al. 2004; Javadzade, Shari rad et al. 2012) .

Individuals with low health literacy are less aware of

their health status, receive fewer preventive services, are

under less control for chronic diseases, have poorer phys-

ical and mental health performance, and make greater

use of the emergency department and hospital services

(Peerson and Saunders 2009). Despite the critical impor-

tance of identifying individuals with inadequate health

literacy, healthcare systems’ employees are often less

concerned about this issue. In contributing patients with

inadequate health literacy, particular methods should be

used, including using simple and understandable words

and expressions, using images, getting feedback from

individuals after providing information to them, and

limiting the information provided to the individual at

any meeting (Chew, Bradley et al. 2004).

Low level of health literacy is more common among

the elderly, illiterate individuals, immigrants, individu-

als with low mental health, and those with hyperten-

sion and type II diabetes. Low health literacy also causes

increased mortality, decisions on certain health risk

behaviors, and failure to perform preventive behaviors

such as screening tests and, thus, poor physical health

(Williams, Baker et al. 1998; Kalichman, Benotsch et al.

2000; Kalichman and Rompa 2000; Schillinger, Grum-

bach et al. 2002; Kindig, Panzer et al. 2004). Health lit-

eracy in chronic patients such as patients with diabetes

who require self-care plays an essential role, which is

why attention to the issue of health literacy in patients

with diabetes has been growing in importance (Khosravi,

Ahmadzadeh et al. 2015).

Chronic diseases affect patients for many years. For

this reason, as long as these conditions are not properly

managed and controlled, no further healthcare services

are received, which leads to reduced quality of life and

health (Esmaeili Shahmirzadi, Shojaeizadeh et al. 2012).

Psychological aspects of diabetes have attracted atten-

tion of many experts in this area as this disease leads

to many behavioral problems in patients. Psychological

factors associated with quality of life can have a great

impact on the quality of patients’ lives. Accordingly,

the results of previous studies in this area indicate that

mood factors are involved in the prevention of diabe-

tes in patients with diabetic retinopathy (McDarbyc and

Acerinie 2014; Moayedi, Zare et al. 2015; Seyedoshoha-

daee, Kaghanizade et al. 2016).

Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes (Mohan,

Sandeep et al. 2007; Seyedoshohadaee, Kaghanizade

et al. 2016; Varvani Farahani, Rezvanfar et al. 2016), the

present study was conducted in 2015 with the aim to

determine the relationship between health literacy and

general health status of patients with type II diabetes in

Ilam City.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this descriptive-correlational study, according to pre-

vious studies conducted in the eld (Seyedoshohadaee,

Kaghanizade et al. 2016), 250 individuals with diabetes

in Ilam City participated in the study. The inclusion cri-

teria were residence in the city of Ilam, ability to read

and write, having type II diabetes, and lack of known

mental disorders. In this study, the participants were

selected using convenience sampling; accordingly, the

researcher went to the Shahid Mostafa Khomeini and

Imam Khomeini hospitals in Ilam City every morning

and gave the questionnaire to diabetes patients who

met the inclusion criteria. The questionnaires were com-

pleted through self-report.

To collect the health literacy data, the Persian version

of the Test about Functional Health Literacy in Adults

(TOFHLA) was used, which was previously validated

by Tehrani Bani Hashemi et al. (Tehrani Banihashemi,

Amirkhani et al. 2007). The questionnaire consists of

two parts of computation and reading comprehension.

The reading comprehension part has 50 items and exam-

ines patients’ ability in reading authentic healthcare

texts. The computation part evaluates patients’ ability

to understand and act based on the recommendations

given to them by physicians and healthcare educators,

which require computation. This part contains 10 health

instructions or orders on prescribed drugs, time to go

to the doctor, stages of use of grants, and an example

of the result of a medical test. Each item in the read-

ing comprehension part was given 1 point (a total of

50 points), and the items (a total of 17) in the computa-

tion part were given a total of 50 points by multiplying

coef cients for an overall of 100 points for the items

in the questionnaire. Based on the point of separation

of 59 and 74, the participants’ health literacy level was

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HEALTH LITERACY AND GENERAL HEALTH STATUS OF PATIENTS 139

Milad Borji et al.

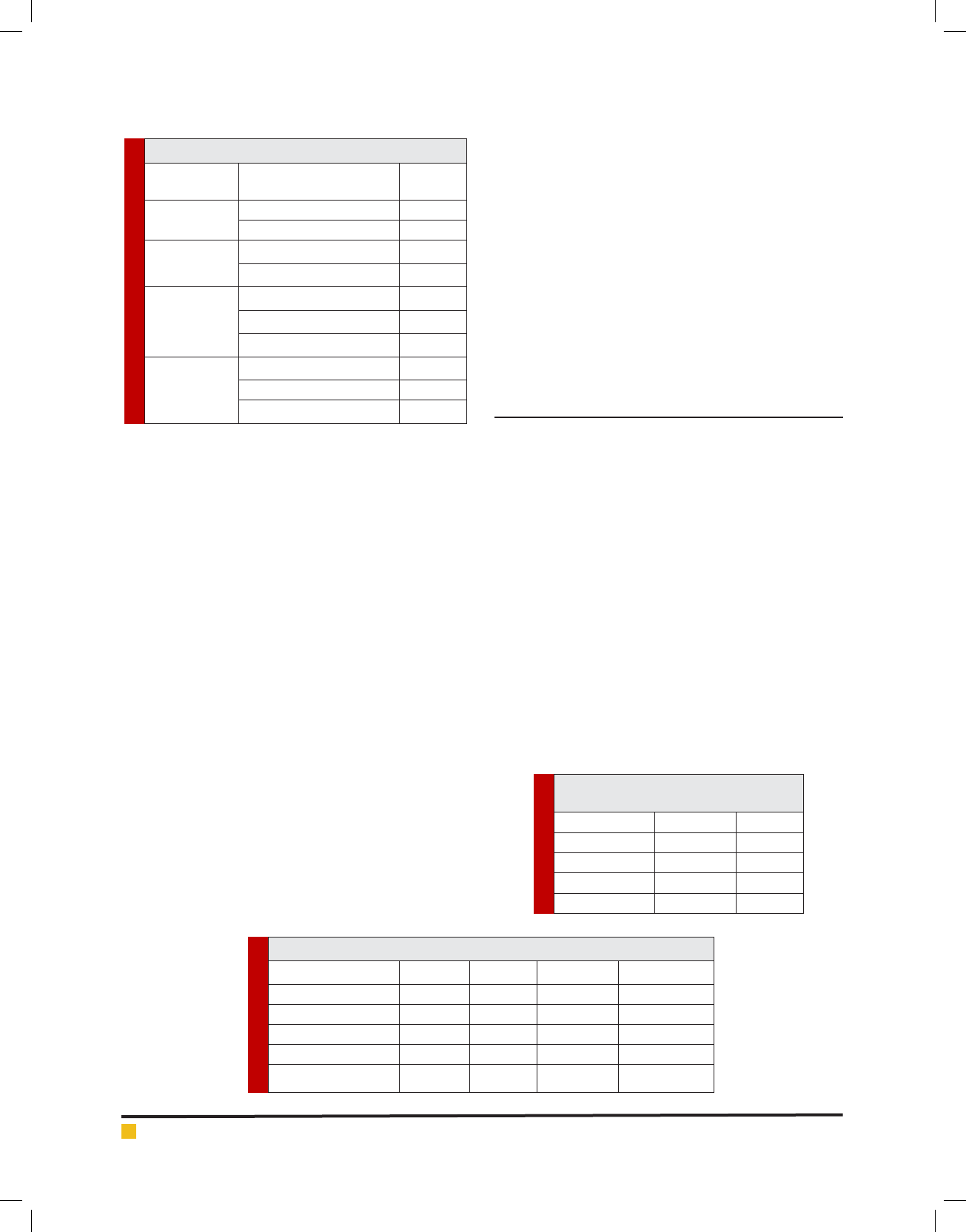

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients

N(%)Sub-Categories

Demographic

features

107(42.8)Male

Gender

143(57.2)Female

153(61.2)Married

Marital Status

97(38.8)illiterate

54(21.6)Below Diploma

Education 141(56.4)Diploma

55(22)Collegiate

92(36.8)Less than 500 thousand Rials

income 116(46.4)500 to 1 million

42(16.8)More than 1 million

Table 2. Frequency distribution of

patients’ health literacy scores

PercentFrequencyhealth literacy

3280inadequate

40.8102marginal

27.268adequate

100250Total

Table 3. Frequency distribution of patients’ general health scores

M(SD)inadequateaverageadequategeneral health

12.39(5.27)118(47.2)120(48)12(4.8)physical health

12.88(5.33)127(50.8)113(45.2)10(4)anxiety and insomnia

13.60(5.26)241(96.4)0(0)9(3.6)social dysfunction

13.49(5.12)244(97.6)0(0)6(2.4)depression

52.30(18.90)98(39.2)144(57.6)8(3.2)Total

classi ed into three levels of inadequate, marginal, and

adequate.

The points were considered based on the proposal

by the instrument designers (Tehrani Banihashemi,

Amirkhani et al. 2007). The reliability of this question-

naire was computed as 0.79 for the computation part

and 0.88 for the comprehension part, in the study by

Javadzade on the elderly (Javadzade, Shari rad et al.

2012)The General Health Questionnaire-28, designed

and developed in 1972 by Goldberg, was used to meas-

ure general health status. The questionnaire encompasses

the following four dimensions: physical health (items

1-7) & anxiety and insomnia (items 8-14) & social dys-

function (items 15- 21) & depression (items 22-28). Each

item in the questionnaire was accompanied by a 4-point

Likert-type response scale consisting of “seldom” (0),

“usually” (1), “almost more than usual” (2), and “often

more than usual” (3) (Seyedoshohadaee, Kaghanizade et

al. 2016). The minimum scores(0) and maximum scores

were ( 84).

For each subscale, The minimum scores (0) and maxi-

mum scores were (21). Regarding subscales, the scores

14–21, 6–13, and <5 were considered indicators of inad-

equate, average, and adequate general health status,

respectively. On the other hand, general health scores of

57–84, 24–56, and <24 were also considered inadequate,

average, and adequate, respectively (Salehi, Mirbehba-

hani et al. 2014).

After obtaining permission from the Ethics Commit-

tee at Ilam University of Medical Sciences, the researcher

initiated the research study. The participants were told

that their participation was voluntary and that all their

personal information was to be kept con dential. They

were also not required to write down their rst and last

names. Data were analyzed with the SPSS Software ver-

sion 20 using t-test (for two groups of variables), ANOVA

(for more than two groups of variables), and correlation

analysis. To analyze the variables, the level of signi -

cance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results showed that the majority of patients mean

(SD) age of 47.46 (9.12) years, Female 143 (57.2%), edu-

cation diplomas 141 (56.4%) and 500 to 1 million 116

(46.4%).

The ndings showed that a majority of participants

with diabetes had marginal health literacy (40.8%) and

average general health (57.6%) (Tables 2 and 3). The nd-

ings also indicated that the means and standard devia-

tions of patients’ health literacy scores were 31.38 ± 6.40,

34.93 ± 7.45, and 6.30 ± 11.61 in terms of calculations,

reading skill, and general health literacy, respectively.

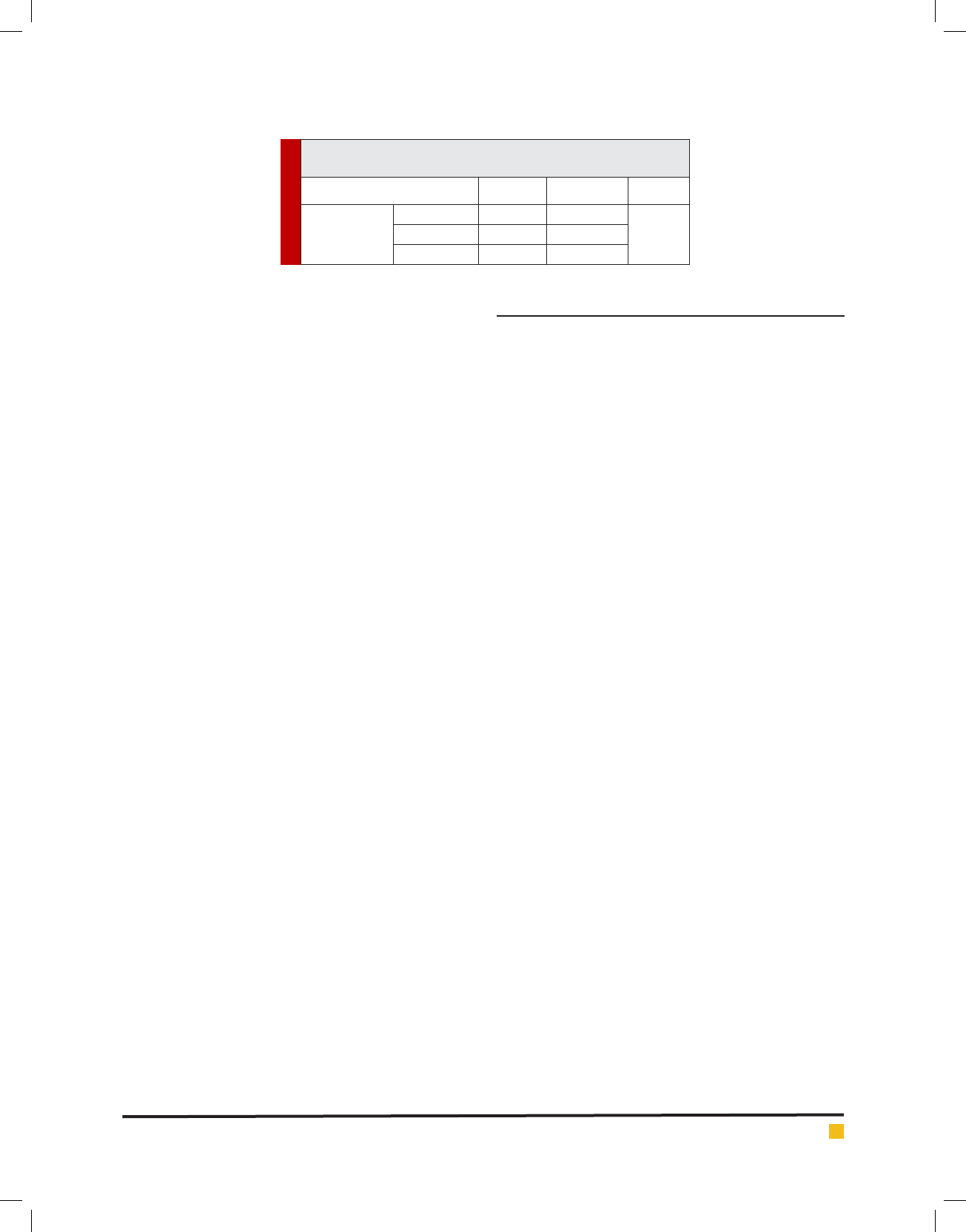

Table 4 shows a signi cant correlation between

health literacy and general health status. Furthermore,

it was observed that the patients with higher levels of

health literacy had a better status in terms of their gen-

eral health (p < 0.001).

According to the ndings, most patients with diabe-

tes (40.8%) had marginal health literacy, and only 27.2

140 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HEALTH LITERACY AND GENERAL HEALTH STATUS OF PATIENTS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Milad Borji et al.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HEALTH LITERACY AND GENERAL HEALTH STATUS OF PATIENTS 141

percent of these patients had adequate health literacy.

This is in a similar vein to the ndings of Arbabi et al.

(Arbabi 2017). investigated the health literacy status in

patients with diabetes referred to clinics in Zabol and

concluded that the majority of patients had marginal

health literacy. However, Rezai Isfahroud et al.’s study,

which aimed to assess the health literacy status in Yazd

Diabetes Research Centers, showed that the health lit-

eracy status was inadequate, marginal, and adequate

in 59.3%, 18.5%, and 22.2% of patients with diabetes

referred to these centers, respectively(Rezaee Esfahrood,

Haerian ardekani et al. 2016).

In a national study conducted by Tavousi et al.

(Tavousi , Aliasghar et al. 2016)on individuals aged 18

to 65 years living in urban areas, one out of two Iranian

people had limited health literacy. Using the TOFHLA,

Molakhalili et al. (Mollakhalili, Papi et al. 2014)also

conducted a study on 384 patients admitted in Isfahan

hospitals and concluded that the mean score of health

literacy was a little greater than average and that most

patients had inadequate health literacy. In the study

by Tehrani Banihashemi et al. (Tehrani Banihashemi,

Amirkhani et al. 2007)on participants aged 18 and older

in ve cities located in Bushehr Province, 28.1%, 15.3%,

and 56.6% of those surveyed had adequate, marginal,

and inadequate levels of health literacy, respectively.

Mozaffari et al.’s study aimed to determine the status

of health literacy in parents with primary school chil-

dren in Ilam using a researcher-made questionnaire.

In this study, the mean scores of health literacy for

fathers and mothers were 19.74 ± 321.64 and 14.08 ±

321.71, respectively. This nding was inconsistent with

the ndings of the current study (Mozafari and Borji

2017).

The ndings of the present study indicated a sta-

tistically signi cant relationship between health liter-

acy of patients with type II diabetes and their general

health status. In this regard, the ndings were con-

sistent with those of Seyedoshohadaee et al. (Seyedo-

shohadaee, Kaghanizade et al. 2016) and Arbabi et al.

(Arbabi 2017). Conversely, Karimi et al.’s study con-

ducted on individuals aged 18 to 64 years in Isfahan

suggested no signi cant relationship between health

literacy and general health status (Karimi, Keyvanara

et al. 2014).

CONCLUSION

Given that health literacy and general health of the

studied patients were not at an acceptable level, it is

necessary to conduct further research to determine the

effects of different training methods and nursing models

toward improving the health status of patients and to

provide grounds for promoting the patients’ health lit-

eracy and general health status.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Th ere is no con ict of interest between authors.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

Ilam University of Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

Arba bi, H. A. M., Ali A Nooshirvani, Sajedeh A Arbab, Azadeh

(2017). The Relationship Between Health Literacy and General

Health in Patients with Type II Diabetes Referring to Diabe-

tes Clinic of Zabol in 2016.Journal of Diabetes Nursing 5(1):

29-39.

Chew , L. D., K. A. Bradley, et al. (2004). Brief questions to

identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Health 11: 12.

Esma eili Shahmirzadi, S., D. Shojaeizadeh, et al. (2012). The

impact of chronic diseases on the quality of life among the

elderly people in the east of Tehran.Journal of Payavard Sala-

mat 6(3): 225-235.

Java dzade, S. H., G. Shari rad, et al. (2012). Relationship

between health literacy, health status, and healthy behaviors

among older adults in Isfahan, Iran.” Journal of education and

health promotion 1.

Kali chman, S. C., E. Benotsch, et al. (2000). Health literacy

and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/

AIDS. American journal of preventive medicine 18(4): 325-

331.

Kali chman, S. C. and D. Rompa (2000). Functional health liter-

acy is associated with health status and health-related knowl-

edge in people living with HIV-AIDS. Journal of acquired

immune de ciency syndromes (1999) 25(4): 337-344.

Kari mi, S., M. Keyvanara, et al. (2014). Health literacy, health

status, health services utilization and their relationships in

adults in Isfahan. Health Inf Manage 10(6): 862-875.

Table 4. Mean scores of health literacy based on the patients’

general health status

p-valueM(SD)N(%)Variable

.000

76.50(14.88)8(3.2)adequate

general health

69.58(10.48)144(57.6)average

60.65(10.56)98(39.2)inadequate

Milad Borji et al.

142 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HEALTH LITERACY AND GENERAL HEALTH STATUS OF PATIENTS BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Khos ravi, A., K. Ahmadzadeh, et al. (2015). Health Literacy

Levels of Diabetic Patients Referred to Shiraz Health Centers

and Its Effective Factors. Health Information Management:

205.

Kind ig, D. A., A. M. Panzer, et al. (2004). Health literacy: a

prescription to end confusion, National Academies Press.

McDa rbyc, J. M. and C. L. Acerinie (2014). Psychological care

of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric dia-

betes 15(20): 232-244.

Moay edi, F., S. Zare, et al. (2015). Anxiety and depression

in diabetic patient referred to Bandar Abbas diabetes clinic.

Bimonthly Journal of Hormozgan University of Medical Sci-

ences 18(1): 65-71.

Moha n, V., S. Sandeep, et al. (2007). Epidemiology of type 2

diabetes: Indian scenario.” Indian Journal of medical Research

125(3): 217.

Moll akhalili, H., A. Papi, et al. (2014). A survey on health lit-

eracy of inpatient’s educational hospitals of Isfahan University

of Medical Sciences in 2012.” Journal of education and health

promotion 3(1): 66.

Moza fari, M. and M. Borji (2017). Assessing the health literacy

level of parents in School children ilam in 2015.Journal of

Nursing Education 5(6): 53-61.

Peer son, A. and M. Saunders (2009). Health literacy revisited:

what do we mean and why does it matter?” Health promotion

international 24(3): 285-296.

Reza ee Esfahrood, Z., A. Haerian ardekani, et al. (2016). A

Survey on Health Literacy of Referred Diabetic Patients to

Yazd Diabetes Research Center. Tolooebehdasht 15(3): 176-

186.

Sale hi, M., N. Mirbehbahani, et al. (2014). General health of

beta-thalassemia major patients in Gorgan, Iran.Journal of

Gorgan University of Medical Sciences 16(1): 120-125.

Schi llinger, D., K. Grumbach, et al. (2002). Association of

health literacy with diabetes outcomes. Jama 288(4): 475-482.

Seye doshohadaee, M., M. Kaghanizade, et al. (2016). The

Relationship Between Health Literacy And General Health In

Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and

Metabolism 15(5): 312-319.

Siho ta, S. and L. Lennard (2004). Health literacy: being able to

make the most of health, National Consumer Council.

Tavo usi , M., H. M. ALIASGHAR, et al. (2016). Health Literacy

In Iran: Findings From A National Study."

Tehr ani Banihashemi, S.-A., M. A. Amirkhani, et al. (2007).

Health literacy and the in uencing factors: a study in ve

provinces of Iran. Strides in Development of Medical Educa-

tion 4(1): 1-9.

Varv ani Farahani, P., M. R. Rezvanfar, et al. (2016). Compar-

ing The Effect Of Multimedia Education With Live Successful

Experiments On Quality Of Life In Type 2 Diabetic Patients.”

Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism 15(5): 320-

329.

Will iams, M. V., D. W. Baker, et al. (1998). Relationship of func-

tional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic

disease: a study of patients with hypertension and diabetes.

Archives of internal medicine 158(2): 166-172.