Health Science

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 10(2): 1-7 (2017)

Pathogens provoking most deaths worldwide: A review

Martin Hessling, Jil Feiertag and Katharina Hoenes

Ulm University of Applied Sciences, Institute of Medical Engineering and Mechatronics, Albert-Einstein-Allee

55, D 89081 Ulm, Germany

ABSTRACT

A list of the globally most important pathogens is generated based on the causes of death statistics published in the

Global Burden Disease study 2015. Pathogens are assigned to the speci ed diseases as far as possible. Dif culties

arises because the death provoking pathogens are often unidenti ed or arise in mixed infections with more than one

pathogenic agent. Furthermore it is possible that a single causative microorganism is involved in different diseases.

For 1.1 of 8.8 million casualties in 2015 no provoking pathogen could be assigned. The identi ed pathogens that are

assumed to cause more than 5 000 deaths annually are speci ed.The resulting list starts with Streptococcus pneumo-

niae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Human immunode ciency virus and Plasmodium falciparum. Together they are

responsible for an estimated 4.7 million casualties which is more than 50% of all deaths provoked by pathogenic

agents in 2015.

KEY WORDS: FATAL PATHOGENS, HI-VIRUS, MYCOBACTERIUM TUBERCULOSIS, PLASMODIUM FALCIPARUM, STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE

1

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: hessling@hs-ulm.de

Received 24

th

March, 2017

Accepted after revision 1

st

June, 2017

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007 CODEN: USA BBRCBA

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2017: 4.31 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2017. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of the most important diseases is essential

for the advancement of public health but sometimes it

is still not enough. At least for infectious diseases often

a more precise information about the major responsible

pathogens is required for future development of medical

prevention measures, like vaccination, or disinfection

techniques for water, air and food. Every few years the

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) pub-

lishes a new version of the Global Burden Disease study

(GBD) with a vast amount of information on the global

health situation. Among this data statistics of cause-

speci c mortality can be found, including the number of

deaths caused by different infections that totals almost

9 million casualties (Wang et al., 2016a). The danger of

premature death is signi cantly higher in the developing

world than in the industrialized countries and according

to the data, children under the age of 5 are particularly

at risk.

These data are not general knowledge, even among

health professionals. Due to vast changes in the last

2 PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

decade caused by effective sanitary and medical meas-

ures like vaccination programs, the worldwide situation

and therefore the death statistics underwent distinct

alteration. Another reason is the large amount of exist-

ing data that impedes the possibility to simply gather an

overview. Lastly the data provided by different organi-

zations within the last few years seems to be slightly

contradictory. The numbers of the UN / Unesco (United

Nations, 2013) give the impression that every 20 sec-

onds a child below 5 years dies of diarrhea caused by

contaminated water which would result in almost 1.6

million dead children per year and would make diarrhea

the globally most important disease. In another word-

ing UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon talked about

more than 800 000 children annually dying of diarrhea

(UN Secretary-General, 2013)which would still make it

the most important disease at least for children below

5 years.

These numbers, that can be found in of cial bro-

chures and speeches, are dif cult to retrace and they are

in contrast to lower values in the Global Burden Disease

study 2010 (Liu et al., 2012) and the even more lower

numbers in the Global Burden Disease studies of 2013

(Murray et al., 2015) and 2015 (Wang et al., 2016a). This

mentioned GBD 2015 study is not only newest but it is

also much more detailed and better documented than

the UN documents and has passed quality criteria like

peer review processes. In conclusion the GBD 2015 study

is most probably the most reliable data source on causes

of death for infections and other diseases.

Due to enhanced medical treatment, including vacci-

nation and improved sanitation and drinking water sup-

ply the number of casualties – published in the different

Global Disease Studies - has fortunately decreased for

many causes of death within the last decade. To con-

tinue this positive development more information on

the causes of death would be helpful. Concerning dis-

eases this means identifying the provoking pathogens.

For some infections caused by a known single micro-

organism this does not represent a problem, but among

the most important illnesses like diarrhea and lower

respiratory tract infections there are many potential

pathogens generating similar symptoms and sometimes

even co-infections caused by more than one pathogen

occur.

The importance of this knowledge is self-evident

for medical treatment like the prescription of antibiot-

ics. But it is also crucial for technical developments like

the application of UV-C water disinfection for diarrhea

prevention in the Developing Countries, one of the top-

ics of our working group (Hessling et al., 2016). Diar-

rhea could be provoked by bacteria like Vibrio cholera

or Escherichia coli or viruses like rotavirus or adeno-

virus. To reduce the concentration of Vibrio cholerae

by three orders of magnitude a UV-C irradiation dose

of about 2.2 J/cm

2

would be necessary. To achieve the

same result for Escherichia coli 5 – 10 J/cm

2

are required

and for rotavirus or adenovirus it would be even25 J/

cm

2

and 100 J/cm

2

, respectively (Chevre ls and Caron,

2006). This clearly shows that not only medication but

also technical developments would actually bene t from

knowing the most important pathogens.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The imaginable approach to create a listing of pathogens

and their number of global casualties by looking for all

known pathogens and count the deaths they provoked

is almost impossible because of two reasons: 1.) There

is the large number of 1400 known human pathogenic

species (Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011) and 2.)

information on the number of deaths doesn´t globally

exist for most of them.

Fortunately there is the Global Burden Disease Study

2015 with information on the world wide health situa-

tion compiled, evaluated and analyzed by a large num-

ber of experts. Among the provided data are statistics

on the global numbers of deaths caused by different dis-

eases (Wang et al., 2016a). The values are rather estima-

tions than exact indications but nevertheless probably

the most accurate, current available numbers and there-

fore they are taken as xed basis for this investigation.

As far as necessary and possible missing data is sup-

plemented by studies published within the last 10 years.

In a rst step all diseases mentioned in (Wang et al.,

2016a), that are provoked by at least one pathogen are

identi ed and in a second step the responsible patho-

gens and their assumed share of casualties is elaborated

(Table 1). This is not always straight forward, because

of complications like incomplete data and due to co-

infections by more than one pathogen.

TUBERCULOSIS AND AIDS

Tuberculosis and AIDS are among the most widespread

infectious diseases with loss of life result. Tuberculosis

is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and is respon-

sible for more than 1.1 million deaths in 2015. AIDS

claimed almost 1.2 million casualties in the same period

(Wang et al., 2016a), but the explicit assignment to a

speci c pathogen is somewhat more complex compared

to Tuberculosis. AIDS is provoked by the HI-virus but

the patients die because of co-infections like tubercu-

losis or pneumoniae or other diseases. Nevertheless the

GBD 2015 study assigns these casualties to AIDS and

this procedure is continued here, wherefore these deaths

are assigned to the HI-virus.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE 3

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

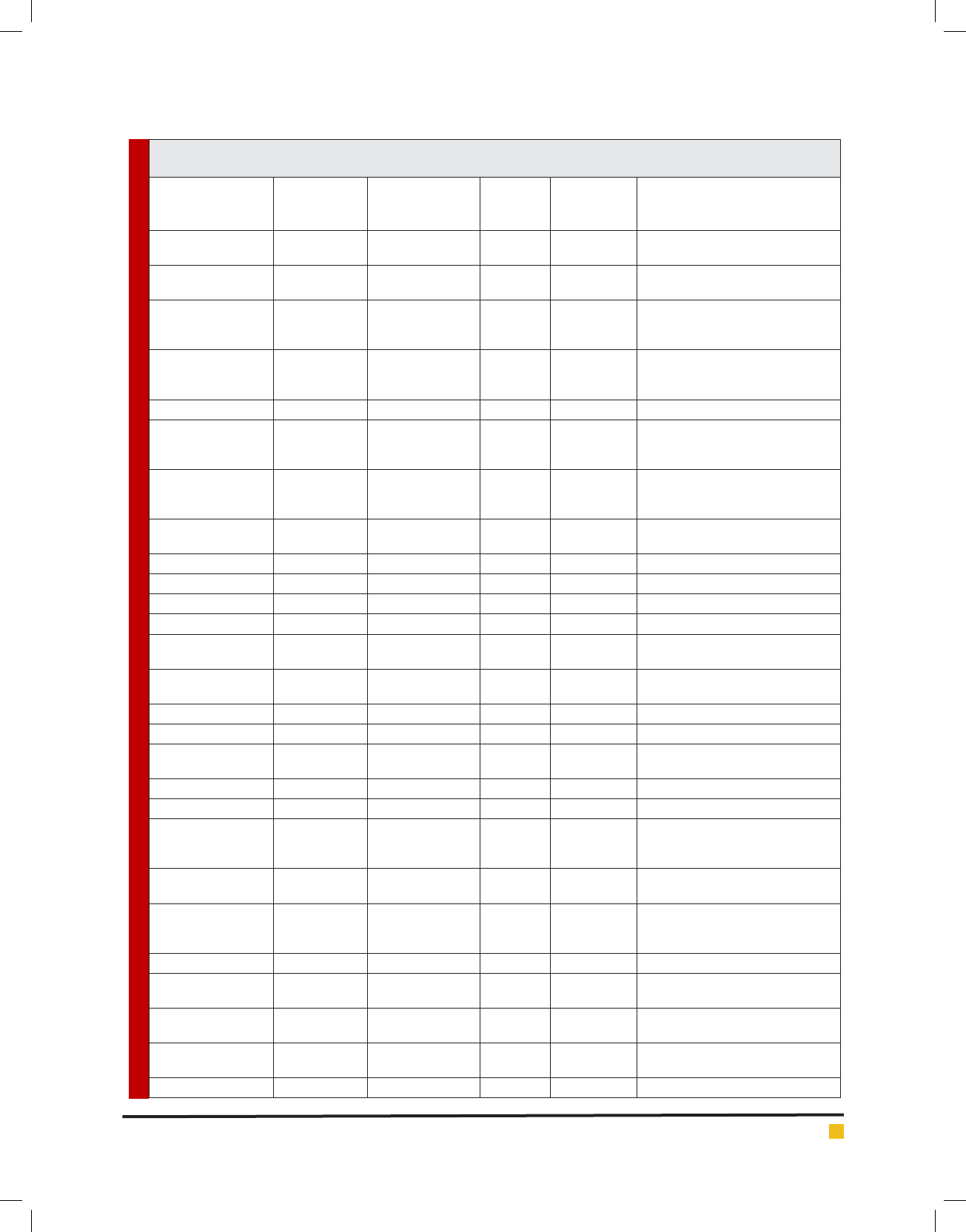

Table 1. Diseases listed in GBD 2015, with number of casualties and responsible pathogens and their estimated share of

cases of deaths.

Disease Total

casualties

[Thousands]

Pathogen(s) Estimated

share [%]

Estimated

casualties

[Thousands]

Reference / Remark

Lower respiratory

infections

2736.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Pneumococcal

pneumonia

Strectococcus

pneumoniae

55.4 1516.1 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Mycoplasma

pneumonia

Mycoplasma

pneumoniae

10 273.7 (Arnold et al., 2007; Cilloniz and

Torres Antonio, 2016; Loebinger and

Wilson, 2012) (mean value)

Legionnaires’

disease

Legionella spp. 5.3 145.0 (Arnold et al., 2007; Cilloniz and

Torres Antonio, 2016; Loebinger and

Wilson, 2012) (mean value)

In uenza In uenza virus 3 82.1 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Respiratory

syncytial virus

pneumonia

Respiratory

syncytial virus

3 82.1 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Staphylococcus

aureus infection

Staphylococcus

aureus

2.2 60.2 (Cilloniz and Torres Antonio, 2016;

Loebinger and Wilson, 2012; Scott et

al., 2008) (mean value)

H In uenzae type

b pneumonia

Haemophilus

in uenzae type b

2.1 57.5 (Wang et al., 2016b)

unknown etiology 19 520.0

Diarrhoe 1312.1

Rotaviral enteritis Rotavirus 15.2 199.4 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Shigellosis Shigella spp. 12.5 164.0 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Other salmonella

infections

Salmonella spp. 6.9 90.5 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Enterotoxigenic E.

coli infection

Enterotoxigenic E.

coli

5.6 73.5 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Adenovirus Adenovirus 5.4 70.9 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Cholera Vibrio cholerae 5.2 68.2 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Amoebiasis Entamoebea

histolytica

5.2 68.2 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Cryptosporidis Cryptosporidium 4.9 64.3 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Aeromonas Aeromonas spp. 4.3 56.4 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Astrovirus

infection

Astrovirus 3.0 39.4 (Desselberger and Gray, 2013; Elyan

et al., 2014; Higgins et al., 2012;

Lanata et al., 2013)

Campylobacter

enteritis

Campylobacter spp. 2.9 38.1 GBD 2015

Giardiasis Giardia lamblia 2.7 35.4 Mean Value of in- and outpatients in

(Fischer Walker et al., 2010; Lanata et

al., 2013)

Norovirus Norovirus 2.3 30.2 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Enteropathogenic

E. coli infection

Enteropathogenic

E. coli

0.9 11.8 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Chlostridium

dif cile

Chlostridium

dif cile

0.7 9.2 (Wang et al., 2016b)

Vibrio

parahaemolyticus

Vibrio

parahaemolyticus

0.4 5.2 (Fischer Walker et al., 2010)

unknown etiology 21.9 287.3

4 PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

AIDS 1192.6 Human

immunode ciency

virus

100 1192.6 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Tuberculosis 1112.6 Mycobacterium

tuberculosis

100 1112.6 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Malaria 730.5 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Plasmodium

falciparum

99 723.2 (World Health Organization, 2016)

Plasmodium vivax 1 7.3 (World Health Organization, 2016)

Meningitis 379.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Pneumococcal

meningitis

Strecptococcus

pneumonia

30.0 113.8 (Wang et al., 2016a)

H. in uenzae type

b meningitis

Haemophilus

in uenzae type b

18.9 71.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Meningococcal

meningitis

Neisseria

meningitidis

19.3 73.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Listeriosis Listeria

monocytogenes

8.0 30.3 (Loeb et al., 2011; Pleger, 2011; Zueter

and Zaiter, 2015)

Group B

Streptococcus

12.5 47.4 (Pleger, 2011; Zueter and Zaiter, 2015)

unknown etiology 11.3 42.8

Liver cancer due to

hepatitis B

263.1 Hepatitis B virus 100 263.1 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Intestinal infection 178.5 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Typhus Salmonella typhi 83.3 148.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Paratyphus Salmonella

paratyphi

16.3 29.1 (Wang et al., 2016a)

unknown etiology 0.4 0.7

Encephalitis 149.5 unknown etiology 100 149500.0 (Wang et al., 2016a)probably mostly

(herpes simplex) viruses(Davies et al.,

2006; Glaser et al., 2006)

Liver cancer due to

hepatitis C

137.8 Hepatitis C virus 100 137.8 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Syphilis 106.8 Treponema

pallidum

100 106.8 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Hepatitis 105.8 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Hepatitis A Hepatitis A virus 10.6 11.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Hepatitis B Hepatitis B virus 61.8 65.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Hepatitis C Hepatitis C virus 2.4 2.5 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Hepatitis E Hepatitis E virus 25.2 26.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Measles 73.4 Measles virus

(rubeola virus?)

100 73.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Whooping cough 58.7 Bordetella pertussis 100 58.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Tetanus 56.7 Clostridium tetani 100 56.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Leishmaniasis 24.2 Leishmania spp. 100 24.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Dengue fever 18.4 Dengue virus 100 18.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Rabies 17.4 Rabies virus 100 17.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Chags disease 8 Trypanosoma cruzi 100 8.0 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Varicella and herpes

zoster

6.4 Varicella-Zoster-

virus

100 6.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Ebola virus disease 5.5 Ebola virus 100 5.5 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Yellow fever 5.1 Yellow fever virus 100 5.1 (Wang et al., 2016a)

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE 5

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

Schistosomiasis 4.4 Schistosoma spp. 100 4.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Otitis media 3.9 unknown etiology 100 3.9 Most important pathogens:

Respiratory syncytical virus, Corona

virus, Streptococcus pneumoniae

but in most cases viral-bacterial co-

infections (Massa

et al., 2009)

African

trypanosomiasis

3.5 Trypanosoma brucei 100 3.5 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Upper respiratory

infections

3.1 unknown etiology 100 3.1 Most cases probably caused by

(rhino-) viruses (Dasaraju and Liu,

1996)

Intestinal nematode

infections

2.7 Acariasis 100 2.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Diphteria 2.1 Corynebacterium

diphtheriae

100 2.1 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Cystic echinococcosis 1.2 Echinococcus

granulosus sensu

lato

100 1.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Gonococcal infection 0.7 Neisseria

gonorrhoeae

100 0.7 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Cysticercosis 0.4 Taenia solium 100 0.4 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Chlamydial infection 0.2 Chlamydia

trachomatis

100 0.2 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Other infectious

diseases

119.6 unknown etiology 100 119.6 (Wang et al., 2016a)

Total number of

casualties

8820.8

Cases of unknown

etiology

1127.0

DIARRHEAL DISEASES AND LOWER

RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

In 2015 diarrheal diseases resulted in 1.3 million casu-

alties (Wang et al., 2016a). They are caused by a vari-

ety of viral and bacterial pathogens that cannot always

be identi ed. The GBD 2015 supplement (Wang et al.,

2016b) provides some insight in 72% of the cases. Most

important is the rotavirus with about 200 000 casual-

ties but in almost 370 000 cases the provoking agents

remain unidenti ed. By conducting a literature research

on typical diarrheal pathogens and their share of infec-

tions and causes of deaths in other recently published

studies about 80 000 of these cases are assigned to

Astrovirus, Giardia lamblia and Vibrio parahaemolyti-

cus (Table 1), but for 290 000 casualties no probably

provoking pathogen could be nominated.

For lower respiratory tract infections, the data situa-

tion is worse in several aspects. They demand the most

death victims worldwide. In 2015 these were 2.7 mil-

lion, with 1.5 million casualties caused by Streptococcus

pneumoniae alone. But the elucidation of the remaining

cases is even more dif cult compared to the diarrheal

diseases, because for lower respiratory tract infections

there are 100 possible pathogens (Graffelman et al.,

2004) and the GBD supplement provides only informa-

tion on three of them. For three other notorious known

pathogens an estimated guess can be performed by a

literature study, but the cause of death remains unsolved

for more than half a million deceased persons.

OTHER INFECTIONS

Concerning other infections Malaria and Meningitis are

the next most important diseases with a total of more

than 1.2 million annual casualties but only 50 000

cases of unknown etiologies. For some infections, like

encephalitis, no pathogen share could be assigned at all,

but the absolute number is at least smaller compared to

unsolved respiratory infections or diarrheal diseases.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The total number of pathogen casualties in Table 1 is 8.8

million. For about 1.1 million thereof no provoking path-

ogen could be identi ed, but for 7.7 million an assumed

pathogen was assigned. The most important pathogen is

Streptococcus pneumonia with an estimated 1.6 million

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

6 PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

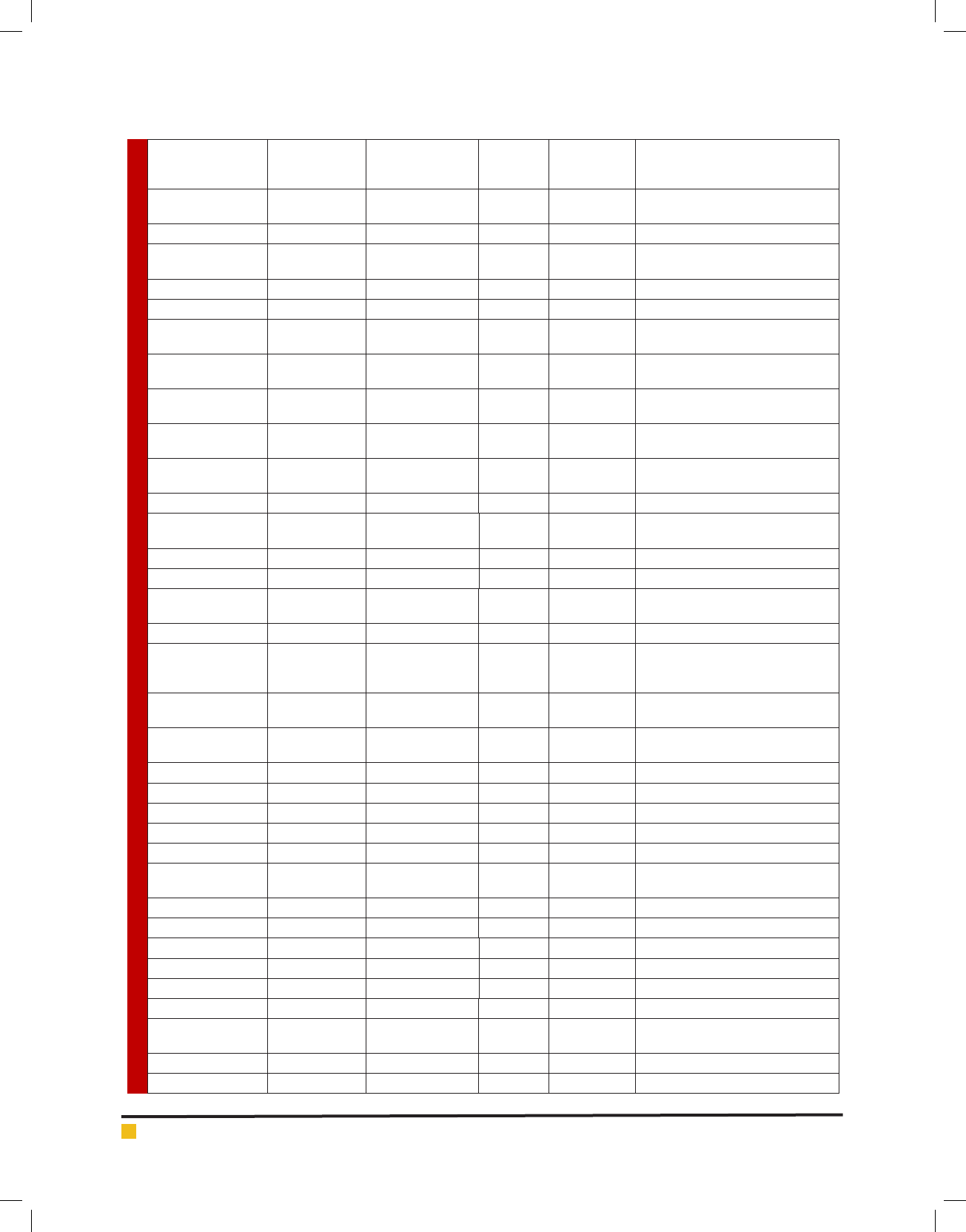

Table 2. Pathogens and estimated number of deaths

for 2015

Pathogen(s)

Estimated

casualties

[Thousands]

Streptococcus pneumoniae 1629.9

Human immunode ciency virus 1192.6

Mycobacterium tuberculosis 1112.6

Plasmodium falciparum 723.2

Mycoplasma pneumoniae 273.7

Hepatitis B virus 328.5

Rotavirus 199.4

Shigella spp. (without S. typhi and S.

paratyphi)

164.0

Salmonella typhi 148.7

Legionella spp. 145.0

Hepatitis C virus 140.3

Haemophilus in uenzae type b 129.1

Treponema pallidum 106.8

Salmonella spp. 90.5

In uenza virus 82.1

Respiratory syncytial virus 82.1

Enterotoxigenic E. coli 73.5

Measles virus 73.4

Neisseria meningitidis 73.2

Adenovirus 70.9

Vibrio cholerae 68.2

Entamoebea histolytica 68.2

Cryptosporidium 64.3

Staphylococcus aureus 60.2

Bordetella pertussis 58.7

Clostridium tetani 56.7

Aeromonas spp. 56.4

Group B Streptococcus 47.4

Astrovirus 39.4

Campylobacter spp. 38.1

Giardia lamblia 35.4

Listeria monocytogenes 30.3

Norovirus 30.2

Salmonella paratyphi 29.1

Hepatitis E virus 26.7

Leishmania spp. 24.2

Dengue virus 18.4

Rabies virus 17.4

Enteropathogenic E. coli 11.8

Hepatitis A virus 11.2

Chlostridium dif cile 9.2

Trypanosoma cruzi 8.0

Plasmodium vivax 7.3

Varicella-Zoster-virus 6.4

Ebola virus 5.5

Vibrio parahaemolyticus 5.2

Yellow fever virus 5.1

annual casualties. Subsequent representatives in the list

of most deadly pathogens are Human immunode ciency

virus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Plasmodium fal-

ciparum, causing1.2, 1.1 and 0.7 million further deaths

in 2015. These four pathogens claim more than 50% of

all 8.8 million casualties. A list containing all pathogens

(responsible for more than 5000 casualties) is displayed

in Table 2.

It might be surprising, that some of the most well-

known notorious diarrheal pathogens like Vibrio chol-

erae or E. coli seem to be of minor importance. Rea-

sons might be the plurality of other diarrhea provoking

agents, especially rotavirus as well as the enhancement

of worldwide sanitary measures and improved drinking

water supplies within the last decades.

Finally it should be emphasized, that all these num-

bers are estimations lacking high precision. The GBD

2015 values providing the basis for this evaluation were

regarded as xed and awless, but actually they have

large uncertainties and the same is true for the comple-

mentations and estimations we provided. Nevertheless,

to our knowledge these numbers are the best and most

precise that exist for this kind of discussion.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no con ict of interest.

REFERENCES

Arnold FW, Summersgill JT, Lajoie AS, Peyrani P, Marrie TJ,

Rossi P, et al. (2007) A worldwide perspective of atypical path-

ogens in community-acquired pneumonia. American jour-

nal of respiratory and critical care medicine 175(10): 1086–

1093.

Chevre ls G and Caron É (2006) UV Dose Required to

Achieve Incremental UV Dose Required to Achieve Incremen-

tal Log Inactivation of Bacteria, Protozoa and Viruses. IUVA

News(8(1)): 38–45.

Cilloniz C and Torres Antonio (2016) Community acquired

pneumonia 2000-2015: What is new? BRN Reviewa 2016(2):

253–273.

Dasaraju PV and Liu C (1996) Infections of the Respiratory Sys-

tem. In: Baron S (ed.) Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX).

Davies NWS, Sharief MK and Howard RS (2006) Infection-

associated encephalopathies: their investigation, diagnosis,

and treatment. Journal of neurology 253(7): 833–845.

Hessling, Feiertag and Hoenes

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS PATHOGENS PROVOKING MOST DEATHS WORLDWIDE 7

Desselberger U and Gray J (2013) Viral gastroenteritis. Medi-

cine 41(12): 700–704.

Elyan D, Wasfy M, El Mohammady H, Hassan K, Monestersky

J, Noormal B, et al. (2014) Non-bacterial etiologies of diarrheal

diseases in Afghanistan. Transactions of the Royal Society of

Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 108(8): 461–465.

Fischer Walker CL, Sack D and Black RE (2010) Etiology of

diarrhea in older children, adolescents and adults: a systematic

review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 4(8): e768.

Glaser CA, Honarmand S, Anderson LJ, Schnurr DP, Forghani

B, Cossen CK, et al. (2006) Beyond viruses: clinical pro les and

etiologies associated with encephalitis. Clinical infectious dis-

eases an of cial publication of the Infectious Diseases Society

of America 43(12): 1565–1577.

Graffelman AW, Knuistingh Neven A, Le Cessie S, Kroes ACM,

Springer MP and van den Broek PJ (2004) Pathogens involved

in lower respiratory tract infections in general practice. The

British journal of general practice the journal of the Royal Col-

lege of General Practitioners 54(498): 15–19.

Hessling M, Gross A, Hoenes K, Rath M, Stangl F, Tritschler H,

et al. (2016) Ef cient Disinfection of Tap and Surface Water

with Single High Power 285 nm LED and Square Quartz Tube.

Photonics 3(1): 7.

Higgins G, Schepetiuk S and Ratcliff R (2012) Aetiological

importance of viruses causing acute gastroenteritis in humans.

Microbiology Australia 2012(33(2)): 49–52.

Lanata CF, Fischer-Walker CL, Olascoaga AC, Torres CX, Aryee

MJ and Black RE (2013) Global causes of diarrheal disease

mortality in children <5 years of age: a systematic review. PloS

one 8(9): e72788.

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al.

(2012) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality:

An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since

2000. The Lancet 379(9832): 2151–2161.

Loeb M, Smaill F and Smieja M (2011) Evidence-Based Infec-

tious Diseases. s.l.: BMJ Books.

Loebinger MR and Wilson R (2012) Pneumonia. Medicine

40(6): 329–334.

Massa HM, Cripps AW and Lehmann D (2009) Otitis media:

viruses, bacteria, bio lms and vaccines. The Medical journal of

Australia 191(9 Suppl): S44-9.

Nature Reviews Microbiology 9(9) Microbiology by numbers:

628 (2011).

Murray et al. (2015) Global, regional, and national age–sex

speci c all-cause and cause-speci c mortality for 240 causes

of death, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Bur-

den of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 385(9963): 117–171.

Pleger N (2011) Bakterielle Meningitis: Eine szientometrische

Analyse. PhD thesis, Charite - University Hospital. Berlin.

Scott JAG, Brooks WA, Peiris JSM, Holtzman D and Mulhol-

land EK (2008) Pneumonia research to reduce childhood mor-

tality in the developing world. The Journal of clinical investi-

gation 118(4): 1291–1300.

UN Secretary-General (Ban Ki-moon) (2013) Message for

World Toilet Day.

United Nations (2013) UN-Water factsheet on sanitation.

Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter

A, et al. (2016a) Global, regional, and national life expectancy,

all-cause mortality, and cause-speci c mortality for 249 causes

of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Bur-

den of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet 388(10053):1459–1544.

Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter

A, et al. (2016b) Supplementary appendix to: Global, regional,

and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-

speci c mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A sys-

tematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.

Supplementary appendix. The Lancet 388(10053): 1459–1544.

World Health Organization (2016) World Malaria Report 2015.

Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zueter AM and Zaiter A (2015) Infectious Meningitis. Clinical

Microbiology Newsletter 37(6): 43–51.