Medical

Communication

Biosci. Biotech. Res. Comm. 9(4): 756-761 (2016)

Risk factors associated with hepatitis B virus disease

in different states of North Eastern India and their

distribution

Namrata Kumari

1

, Priyanka Kashyap

1

, Snigdha Saikia

1,2

, Kangkana Kataki

1

,

Subhash Medhi

1

, Bhavadev Goswami

2

, Premashis Kar

3

, Th. Bhimo Singh

4

, K.G Lynrah

5

,

M. R. Kotowal

6

, Pradip Bhaumik

7

, Moji. Jini

8

and Manab Deka

1

1

Bioengineering and Technology Department, Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam

2

Department of Gastroenterology , Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati, Assam

3

Department of Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi

4

Department of Medicine, Regional Institute of Medical Sciences Regional Medical College,Imphal

5

Deptartment of Medicine, NEIGRIHMS, Shillong, Meghalaya

6

Medical Adviser to the Hon’ble Chief Minister of Sikkim, STNM Hospital, Gangtok, Sikkim

7

Dept of Medicine, Agartala Govt. Medical College, Agartala, Tripura.

8

Directorate of Medical Education , General Hospital, Naharlagun, Arunachal Pradesh.

ABSTRACT

To determine whether risk factors such as fever, anorexia, abdominal discomfort, haematemesis, weight loss, high coloured urine,

blood transfusion, alcoholic intake and multiple sexual partners are highly associated and derive a novel risk score for the devel-

opment of HCC. Different liver diseases were screened for the positivity of HBsAg were were followed up (mean Age and SD) for

the occurrence of HCC. The risk factors were recorded and found the statistical signi cant with the disease. The distribution of the

different categories of HBV disease in six different states of Northeastern India region were recorded .The number of Chronic cases

are found as the highest followed by Acute viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, HCC and FHF. The mean Age±SD of HCC was was recorded as

53.3 ± 9.57 which was greater than other study groups of HBV. The risk factors such as fever, high coloured urine, blood transfu-

sion and Multiple sexual partners were recorded as mostly signi cant(p<0.05). These risk factors are closely associated with the

progression of the liver diseases than other recorded in this study . The other risk factors were also recorded and the values were

not found as a highly associated but may be increase up to a level . The risk score, based on the present and absent of the factors

can estimate the chance of development of HCC in few years . It can be used to identify high-risk CHB patients for treatment and

screening of HCC.

756

ARTICLE INFORMATION:

*Corresponding Author: namrata388@gmail.com

Received 14

th

Sep, 2016

Accepted after revision 15

th

Dec, 2016

BBRC Print ISSN: 0974-6455

Online ISSN: 2321-4007

Thomson Reuters ISI ESC and Crossref Indexed Journal

NAAS Journal Score 2015: 3.48 Cosmos IF : 4.006

© A Society of Science and Nature Publication, 2016. All rights

reserved.

Online Contents Available at: http//www.bbrc.in/

Namrata Kumari et al.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B is a public health problem and more than

350 millionpeople are said to be infected with the hepa-

titis B virus worldwids (Kim et. al., 2016) . Hepatitis B

virus infection is mainly associated with an acute liver

disease which includes liver failure and also chronic-

ity which can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer (Liang

et. al., 2009). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major blood-

borne and sexually transmitted infectious agent that is

a signi cant global public health issue Currently, eight

HBV genotypes (A-H) have been described and diverge

by at least more than eight per cent in their nucleotide

sequences (Kramvis et. al., 2005). The occult hepatitis B

virus infection is de ned as “the presence of HBV DNA

in the liver (with detectable or undetectable HBV DNA

in serum) in individuals testing HBsAg negative by cur-

rently available assays” (Raimondo 2008; Hollinger 2010

and Metaferia et. al., 2016).

Earlier, naturally occurring deletions in the pre-S2/S

promoter region were observed in several cases of occult

HBV infection (Chaudhuri 2004; Mu 2009), chronic HBV

infection (Fan et al., 2001), and patients with progressive

liver diseases (Chen et. al.,2006) . In a subsequent study, it

was demonstrated that these deletions can cause altered

surface protein expression, and an increased large-

HBsAg (L-HBsAg) to major/small-HBsAg (S-HBsAg)

ratio leading to reduced HBsAg secretion (Sengupta

et al., 2007).

HBV is spread predominantly by percutaneous or

mucosal exposure to infected blood and other body u-

ids with numerous forms of human transmission. The

sequelae of HBV infection include acute and chronic

infection, cirrhosis of the liver and primary liver can-

cer. The likelihood of progression to chronic infection is

inversely related to age at the time of infection. Around

90% of infants infected perinatally become chronic car-

riers, unless vaccinated at birth. The risk for chronic

HBV infection decreases to 30% of children infected

between ages 1 and 4 years and to less than 5% of per-

sons infected as adults (McQuillan 1999; Wasley 2010).

Healthcare personnel are at increased risk of occupa-

tional acquisition of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

While effective vaccination for HBV is widely available,

the prevalence of HBV and vaccine acceptance in hospital

personnel have not been recently assessed.Some liver dis-

eases are potentially preventable and are associated with

lifestyle choices. Alcohol-related liver disease is due to

excessive consumption and is the most common prevent-

able cause of liver disease.Hepatitis B is a viral infection

most often spread through the exchange of bodily u-

ids (for example, unprotected sexual intercourse, sharing

unsterilized drug injecting equipment, using non-steri-

lized equipment for tattoos or body piercing).

The hereditary liver disease can be passed geneti-

cally from generation to generation. Examples include

Wilson’s disease (copper metabolism abnormalities) and

hemochromatosis (iron overload). Chemical exposure

may damage the liver by irritating the liver cells resulting

in in ammation (hepatitis), reducing bile ow through

the liver (cholestasis) and accumulation of triglycerides

(steatosis). Obesity/overweight increases the risk for liver

disease. Obesity often results in the accumulation of fat

cells in the liver. Acids that are secreted by these fat

cells (called fatty acids) can cause a reaction in the body

that destroys healthy liver cells and results in scarring

(sclerosis) and liver damage.From previous studies in

Ethiopia have demonstrated that the important factors

of HBV transmission include blood transfusion; tattoo-

ing; a history of surgery, unsafe injections, or abortions;

multiple sexual partners; and traditional practices such

as scari cation, circumcision, and also ear piercing

(Awole 2005; Walle 2008; Ramos 2011; Zenebe 2014;

Tegegne 2014) .Although the association between HIV

and HBV has become less prominent in Africans, evi-

dence has been found indicating that HIV makes HBV-

related liver disease develop more quickly (Metaferia

et. al., 2007) and HIV/HBV co-infection has serious

effects on both pregnant women and infants. A previous

study among pregnant women in Bahir Dar city showed

an HIV/HBV co-infection rate of 1.3% (Chen et. al., 2006)

. The risk of developing liver disease varies, depending

on the underlying cause and the particular condition.

General risk factors for liver disease include alcoholism,

exposure to industrial toxins, heredity (genetics), and

long-term use of certain medications.

Age and gender also are risk factors for liver disease.

These factors vary, depending on the particular type of

disease. For example, women between the ages of 35

and 60 have the highest risk for primary biliary cirrhosis

and men aged 30-40 are at higher risk for primary scle-

rosing cholangitis.

In our study we have included the following factors

having unprotected sex with more than one partner or

with an infected partner , Having a sexually transmit-

ted disease (STD) ,Using IV (injected) drugs ,Living with

an infected person , Having end-stage kidney disease

and receiving hemodialysis treatments,Being exposed to

human blood at work (e.g., health care workers) .

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study area: The North-eastern region, where the where

the study was conducted, is a less developed region of

India in terms of economic, social, and health indices.

Insuf cient health services and lack of public awareness

of health-related issues have increased the prevalence of

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS THE RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH HEPATITIS B VIRUS DISEASE 757

Namrata Kumari et al.

diseases, particularly communicable diseases. In order to

achieve the objectives of the study, we enrolled patients

with various types of liver diseases seen at various par-

ticipating centre of Northeastern states which include

Regional Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal, Manipur;

Agartala Govt. Medical College, Tripura; STNM Hospi-

tal, Gangtok, Sikkim; Naharlagun General Hospital,

Arunachal Pradesh,Gauhati Medical College, Guwahati,

Assam; NEIGRIHMS, Shillong, Meghalaya .Patients with

HBV infection who had achieved a virological response

were collected and recorded the data since Nov 2012 to

May 2015.

CLINICAL DATA

The patients of AVH were evaluated on the basis of history

and clinical examination. The liver function tests (LFT)

was done at the rst visit. The patients of Acute Viral

Hepatitis (AVH), Fulminant Hepatic Failure (FHF) were

evaluated on the basis of history, physical examination,

liver function test and serological test for HBsAg. Sam-

ples which were positive for HBsAg were also screened

for IgM anti-HBc and HBV-DNA. To rule out any co-

infection with other hepatotropic viruses IgM anti-HAV,

anti-HCV, IgM, anti-HEV infection was done. The patients

of chronic liver disease viz. chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis of

the liver and hepatocellular carcinoma was evaluated on

the basis of history, physical examination, Liver function

pro le, Prothrombin time, serological markers for HBsAg.

Samples which are positive for HBsAg were further tested

for IgG anti-HBc and HBeAg followed by HBV DNA.

Anti-HCV and HCV RNA was done in the cases which are

positive for HBV DNA to rule out cases of co-infection.

The serum of voluntary blood donor was collected from

blood banks of all the hospitals .They were screened for

HBsAg using commercially available ELISA kits (3rd gen-

eration) at each centre.Serum samples from each subject

were stored at -80®C until use. The patients with HCC

cases, the serum samples were collected at the time when

liver biopsy was performed.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the study:

All those patients who were clinically diagnosed as

Acute Viral Hepatitis (AVH), Fulminant Hepatic Failure

(FHF), chronic active hepatitis (CAH), Cirrhosis, Hepa-

tocellular Carcinoma (HCC) were included in the study.

Voluntary blood donors and Healthcare workers were

also included in this study. Professional blood donors,

high-risk group like IV drug abusers will be excluded

from the study.

EXTRACTION OF HBV DNA

HBV DNA was extracted using slightly modi ed Phenol-

Chloroform method as described by Teresa Santantonio

et al 1991. Brie y the method involves 100 μl of serum

sample incubated with 0.5% SDS, 10mM Tris-HCl (pH-

7.5), 10mm EDTA & 10mg / ml Proteinase K at 37°C

overnight. Then the serum DNA would be extracted

twice with Phenol / Chloroform and precipitated with

ethanol in the presence of 30 μg of tRNA. The pallet was

air dried and resuspended in 25 μl of distilled water.Part

of the surface gene (nucleotide position 425 to position

840) was ampli ed by nested polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) for the HBV DNA.

Study design

Before starting the study, approval from the local ethi-

cal committee was received, and those subjects over the

age of 15 who had consented to participate in the study

were included. Informed consent forms, as well as infor-

mation about the aims of the study, were provided for

each subject. Age, residence site (rural/urban), a level of

education, and marital status of the subjects, and any

family history of jaundice were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables of HBV diseases were reported as

a number of cases and were grouped into states. The

statistical analysis was done by using the SPSS version

13.1 to con rm the association.For the descriptive anal-

yses, we calculated the values and were presented as

either a number (percent;%) or mean SD (standard devi-

ation). Statistical signi cance levels were determined by

two-tailed tests and considered the signi cant P value <

0.05 (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis data were plotted in

excel.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DEMOGRAPHICS AND OUTCOMES

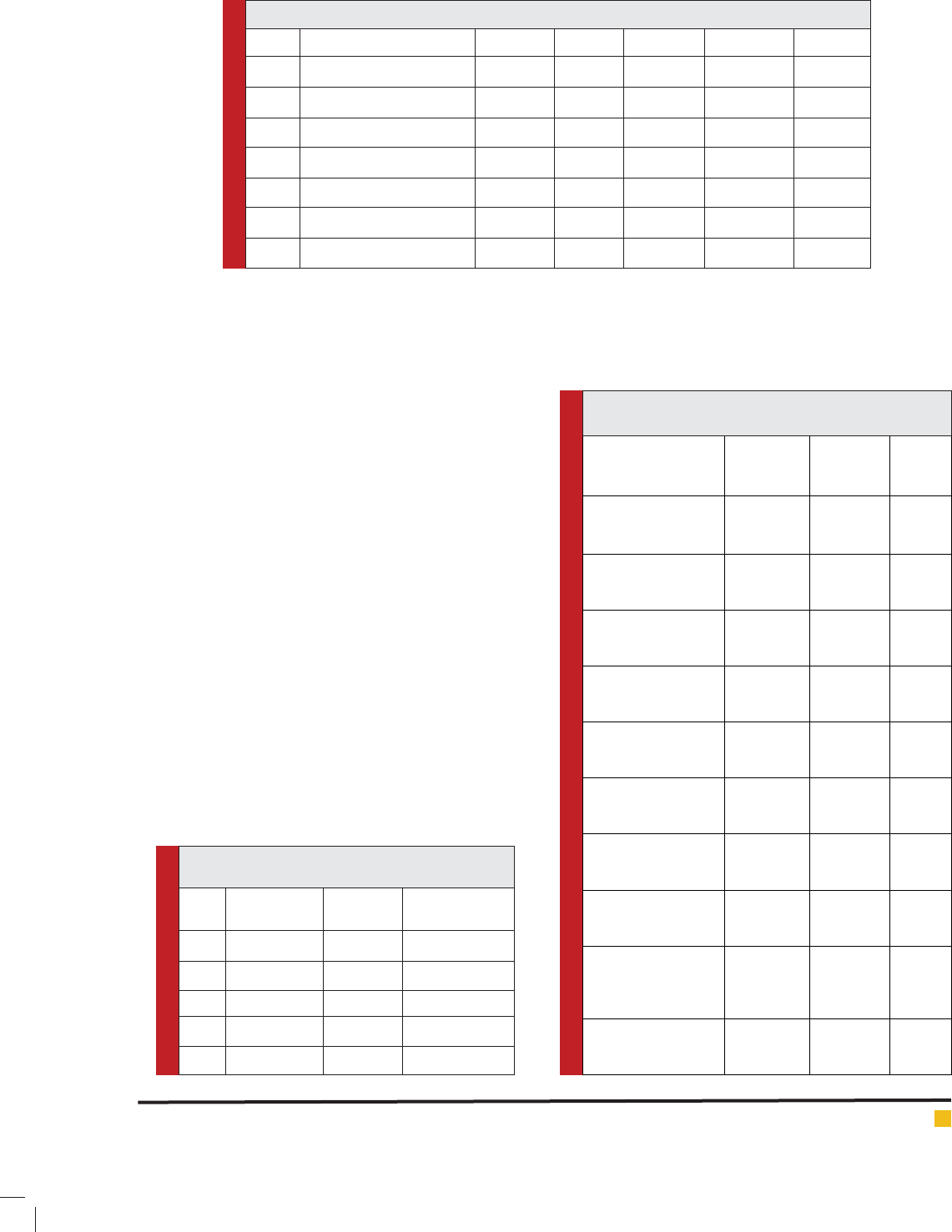

The distribution of the different categories of HBV dis-

ease in six different states of Northeastern India region

is shown in Table1. Different states have the distribu-

tion in different ranges and the numbers were showed

in the rst table. The number of Chronic cases is found

as the highest followed by Acute viral hepatitis, cirrho-

sis, HCC, and FHF. All the values were recorded and a

bar graph was plotted to express the distribution levels.

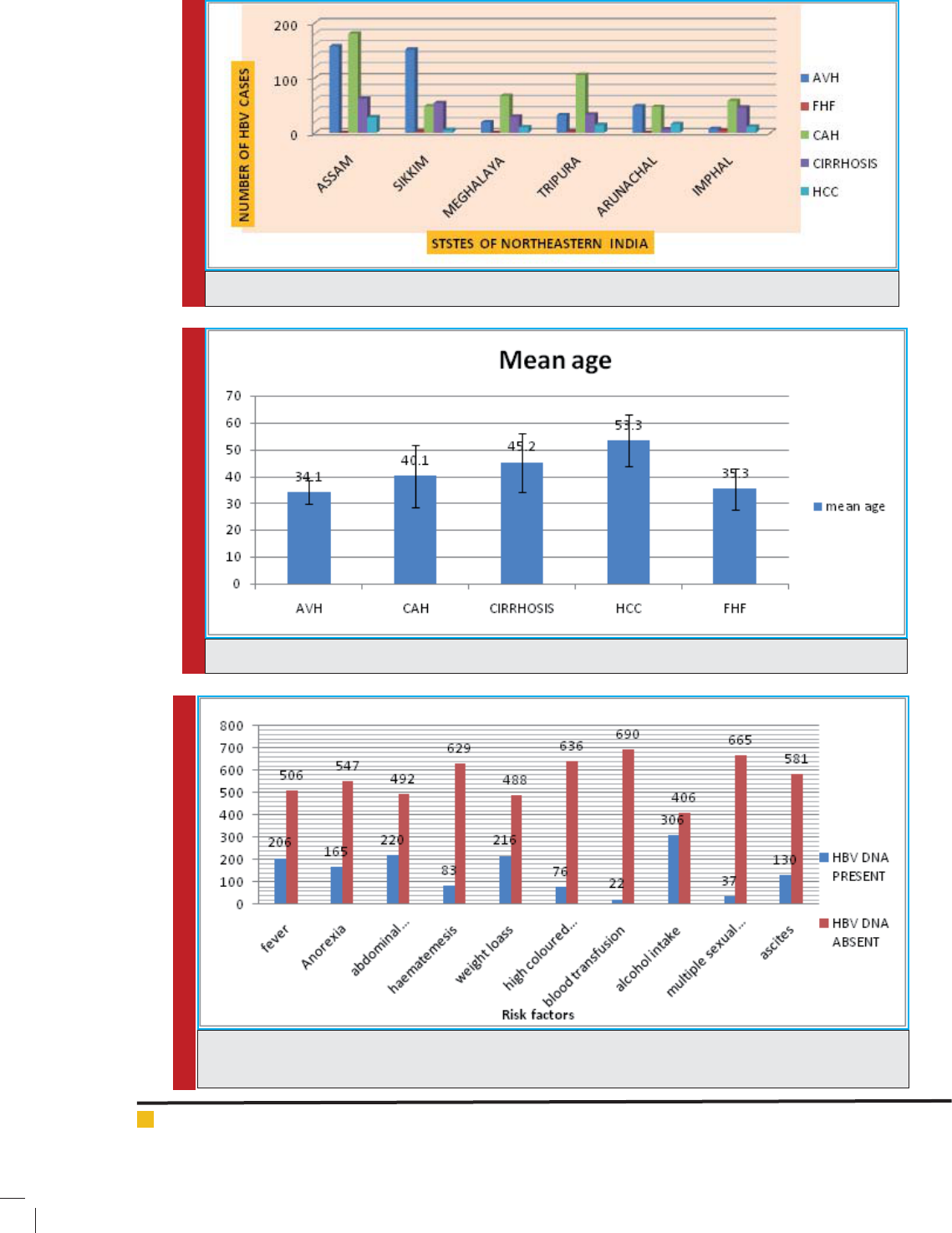

The mean and S.D values of age were also recorded and

it was distributed among all the groups of the disease

infected cases of Hepatitis B virus. The table 2 showed

all the mean and S.D values of the different stages of

liver disease. The table 3 showed the risk factors of

HBV-related liver diseases were recorded and which

indicated the factors such as fever, anorexia, Abdomi-

nal discomfort,Haematemesis,weight loss, High coloured

urine, blood transfusion, alcoholic intake, multiple sex-

758 THE RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH HEPATITIS B VIRUS DISEASE BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Namrata Kumari et al.

Table 1: Distribution of HBV infection among the different parts of North Eastern India.

S. NO STATES AVH FHF CAH CIRRHOSIS HCC

1 ASSAM (n=427,34.4%) 157 0 180 62 28

2 SIKKIM (n=260,20.9%) 151 2 48 54 5

3 MEGHALAYA (n=125,10%) 19 0 67 29 10

4 TRIPURA (n=186 ,14.98%) 32 2 105 33 14

5 ARUNACHAL (n=117 ,9.4%) 48 0 47 6 16

6 IMPHAL (n=126,10.1%)) 7 4 58 46 11

TOAL (n=1241) 414(33.3%) 8(0.64%) 505(40.7%) 230 (18.5%) 84 (6.76%)

Table2: The mean age of the study groups among

various categories of the HBV infection.

s. no Study group Number

(n=1241)

Mean Age±S.D

1 AVH 414 34.1 ± 4.33

2 CAH 505 40.1 ± 11.45

3 CIRRHOSIS 230 45.2 ±10.95

4 HCC 84 53.3 ± 9.57

5 FHF 8 35.3 ± 7.83

Table 3: The independent risk factors and their

signi cant role in the progression of the liver disease.

Risk Factors HBV DNA

PRESENT

(n=712)

HBV DNA

ABSENT

(n=571)

P value

Fever:

Present:

Absent :

206(29%)

506(71%)

204(36%)

367(64%)

0.01*

Anorexia:

Present

Absent

165(23%)

547(77%)

144(25%)

427(75%)

0.40

Abdominal Discomfort

Present

Absent

220(31%)

492(69%)

196(34.%)

375(66%)

0.4

Haematemesis:

Present

Absent

83(11%)

629(89%)

66(11%)

505(89%)

0.68

Weight Loss:

Present

Absent

216(30%)

488(70)

183(32%)

382(68%)

0.51

High coloured urine:

Present

Absent

76(11%)

636(89%)

90(16%)

481(84%)

0.003*

Blood Transfusion

Present

Absent

22(3%)

690(97%)

30(4%)

541(96%)

0.004*

Alcohol intake

Present

Absent

306(43%)

406(57%)

263(46%)

308(54%)

0.27

Multiple sexual

partners:

Present

Absent

37(5%)

665(95%)

25(4%)

546(96%)

0.049*

Ascites:

Present

Absent

130

581

95

476

0.44

ual partners, and ascites.In Northeast India HBV is a pre-

dominant underlying disease (52%).

In this report we showed that the CAH was distributed

the highest in number(n=505,40.7%)followedbyAVH(n=

414,33.3%),Cirrhosis(n=230,18.5%),HCC(n=84,6.76%)

and FHF(n=8,0.64%).So the number of FHF was the

least 0.64% among all. The highest number of infections

were recorded in Assam(n=427,34.3%) and the incident

rate of CAH was more and no FHF cases were recorded

during the study. In Sikkim 20.9% prevalence rate was

recorded and the incident rate of AVH(n=151)was the

highest followed by cirrhosis(n=54),CAH(n=48),HC

C(n=5)andFHF(n=2).10% of incident rates were recorded

in Meghalaya and the number of CAH(n=67) were more

than another group of the liver disease. In Tripura, the

HBV positive cases were recorded as 14.98%.Where CAH

was recorded as the highest (n=105) and only a few(n=2)

were recorded as FHF .9.4% of HBV were recorded in

Arunachal Pradesh with AVH(n=48)as the highest inci-

dent rates and no FHF cases were recorded. In Imphal,

only 10.1% cases of HBV were recorded and CAH was

the highest incident .

In the Table2, the mean Age±SD of HCC was was

recorded as 53.3 ± 9.57 which was greater than other

study groups of HBV. The infection with AVH was

recorded as 34.1 ± 4.33 .

The risk factors such as fever ,high coloured urine,

blood transfusion and Multiple sexual partners were

recorded as mostly signi cant(p<0.05).These risk fac-

tors are closely associated with the progression of the

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS THE RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH HEPATITIS B VIRUS DISEASE 759

Namrata Kumari et al.

FIGURE 1. The distribution of the HBV-related liver disease among all the states of NorthEastern India.

FIGURE 2. The distribution of different age groups as means±S.D in different cases of HBV.

FIGURE 3. The independent risk factors of HBV-related liver diseases in all the states by differentiating the

HBV DNA present or absent.

760 THE RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH HEPATITIS B VIRUS DISEASE BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS

Namrata Kumari et al.

liver diseases than other recorded in this study. The other

risk factors were also recorded and the values were not

found as a highly associated but may be increased up

to a level.

In conclusion, it has been demonstrated that the

characteristic of Hepatitis B virus disease HBsAg surface

marker identi cation is the most important to nd the

prevalence rate of the liver disease. Along with the iden-

ti cation of marker, the risk factors are also necessary to

nd so that it may help the physicians to give the treat-

ment and also to reduce the high risk of this disease.So

the awareness should be made among the incident areas.

Finally, the signi cant distribution of major risk factors

raises the possibility of association of this HBV disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

A special acknowledgement goes to Indian Council

Medical Research,New Delhi for providing the funding

to carry out this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

• CHB, chronic hepatitis B

• HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen

• AVH,Acute viral Hepatitis

• HCC,Hepato cellular carcinoma

REFERENCES

Awole M, Gebre-Selassie S. Seroprevalence of HBsAg and its

risk factors among pregnant women in Jimma, Southwest

Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19:45–50.

A. Wasley, D. Kruszon-Moran, W. Kuhnert, E.P. Simard, L.

Finelli, G. McQuillan, et al.The prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus

infection in the United States in the Era of Vaccination J Infect

Dis, 202 (2010),192–201.

Chaudhuri V, Tayal R, Nayak B, Acharya SK, Panda SK. 5.

Occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic liver disease: full-

length genome and analysis of mutant surface promoter. Gas-

troenterology 2004; 127 : 1356-71.

Chen BF, Liu CJ, Jow GM, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Chen DS. High 8.

prevalence and mapping of pre-S deletion in hepatitis B virus

carriers with progressive liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2006;

130 : 1153-68.

Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. 1. Hepatology

2009; 49 (Suppl 5): S13-21.

Kramvis A, Kew M, Francois G. Hepatitis B virus genotypes. 2.

Vaccine 2005; 23 : 2409-23.

Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen 3.

DS, Colombo M, et al. Statements from the Taormina expert

meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2008;

49 : 652-7.

Hollinger FB, Sood G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a 4.

covert operation. J Viral Hepat 2010; 17 : 1-15.

Mu SC, Lin YM, Jow GM, Chen BF. Occult hepatitis B 6. virus

infection in hepatitis B vaccinated children in Taiwan. J Hepa-

tol 2009; 50 : 264-72.

Fan YF, 7. Lu CC, Chen WC, Yao WJ, Wang HC, Chang TT, et

al. Prevalence and signi cance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) pre-S

mutants in serum and liver at different replicative stages of

chronic HBV infection. Hepatology 2001; 33 : 277-86.

Sengupta S, Rehman S, Durgapal H, Acharya SK, Panda SK.

9. Role of surface promoter mutations in hepatitis B surface

antigen production and secretion in occult hepatitis B virus

Infection. J Med Virol 2007; 79 : 220-8.

G.M. McQuillan, P.J. Coleman, D. Kruszon-Moran, L.A. Moyer,

S.B. Lambert, H.S. Margolis Prevalence of hepatitis B virus

infection in the United States: The National Health and Nutri-

tion Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994 Am J Public

Health, 89 (1999), 14–18

Kim DH. Kang HS. Kim KH. Roles of hepatocyte nuclear factors

in hepatitis B virus infection.World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Aug

21;22(31):7017-29.

Metaferia Y. Dessie W. Ali I. Amsalu A. Seroprevalence and

associated risk factors of hepatitis B virus among pregnant

women in southern Ethiopia: a hospital-based cross-sectional

study. Epidemiol Health. 2016 Jun 19;38:27 .

Walle F, Asrat D, Alem A, Tadesse E, Desta K. Prevalence of

hepatitis B surface antigen among pregnant women attend-

ing antenatal care service at Debre-Tabor Hospital, Northwest

Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2008;17:13–20.

Ramos JM, Toro C, Reyes F,Amor A, Gutiérrez F.Seroprevalence

of HIV-1, HBV, HTLV-1 and Treponema pallidum among preg-

nant women in a rural hospital in Southern Ethiopia. J Clin

Virol. 2011;51:83–85.

Tegegne D,Desta K,Tegbaru B, Tilahun T. Seroprevalence and

transmission of hepatitis B virus among delivering women and

their new born in selected health facilities,Addis Ababa, Ethio-

pia: a cross sectional study.BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:239.

Zenebe Y, Mulu W, Yimer M, Abera B. Sero-prevalence and risk

factors of hepatitis B virus and human immunode ciency virus

infection among pregnant women in BahirDar city,Northwest

Ethiopia: a cross sectional study.BMC InfectDis. 2014;14:118.

BIOSCIENCE BIOTECHNOLOGY RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS THE RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH HEPATITIS B VIRUS DISEASE 761